The August 2023 issue of the latest in financial #AdvisorTech kicks off with the news that estate planning platform Wealth.com has launched Ester, an AI-driven “legal assistant” that uses machine learning to help advisors quickly review and extract the key information from clients' estate planning documents, as it joins FP Alpha in the competition to become “Holistiplan for estate planning documents.” Although given Wealth.com's core business as a document preparation service, Ester's success may be better measured by how many new clients it brings in to create new estate planning documents than by its overall market share as a stand-alone estate planning software tool for advisors.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

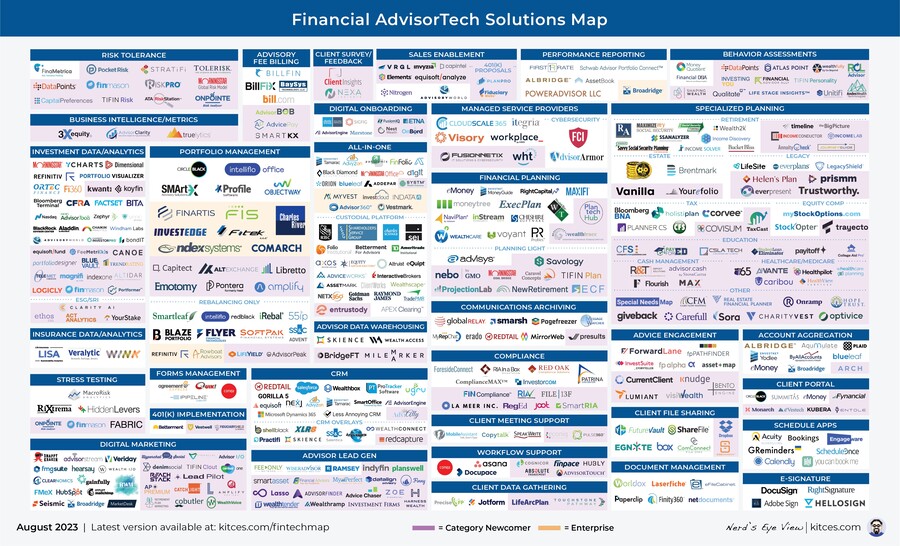

Be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory.

AdvisorTech companies that want to submit tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to TechNews@kitces.com!

One of the most striking AdvisorTech stories in recent years has been that of Holistiplan, which debuted in 2019 as a tool for automatically scanning clients' tax returns and pulling out key information for the purposes of creating client-friendly tax summaries as well as forward-looking tax planning projections. The sheer usefulness of Holistiplan in drastically reducing the time spent on manually reviewing tax returns led it to not only quickly achieve a dominant market share within the category of tax planning software within just a few years (79% market share within the category, according to the latest Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity), but to almost single-handedly turn tax planning software itself into one of the fastest-growing categories on the AdvisorTech map.

In light of Holistiplan's success, it follows that other tech providers would see an opportunity to develop solutions for scanning and digesting other types of client documents — in particular, estate planning documents, which often require advisors to parse many pages of legal boilerplate language to pull out relevant information for summarizing a client's estate plan and devising potential changes. While experience and education (like our own Kitces Course on Reviewing Estate Planning Documents) can help advisors zero in on the key data more quickly with enough practice, ideally it would be better to have a program that makes it possible to skip (or at least summarize, to greatly expedite) the review process entirely and get straight to the recommendations. And as Holistiplan's example shows, a tool that can meaningfully reduce an advisor's time spent on reviewing documents has a clear path to widespread adoption.

The issue, however, is that automatically scanning and summarizing estate planning documents requires a different class of technology than doing the same for tax returns. In contrast to the information on tax returns, which is contained in fillable fields with consistent locations and format on standardized government forms — making it relatively simple to train the software on where to find the key numbers and use simple optical character recognition to retrieve them — the information in will and trust documents is embedded in paragraphs of text that have no standardized format but are instead laid out according to the preferences of whichever attorney drafted them. That means any software made to scan those documents needs to not only “read” the relevant key information, but know where to find that information within the document in the first place.

Against this backdrop, the recent rise of AI tools like ChatGPT (or more generally, the rise of machine learning) that can process and summarize volumes of text nearly instantaneously has clear implications for the task of automatically “reading” complex estate planning documents, and indeed solutions like FP Alpha's Estate Module have worked to harness the power of AI as they try to become Holistiplan for estate planning.

Most recently, estate planning platform Wealth.com has become the latest provider to debut an AI-driven estate planning solution by launching Ester, its so-called “legal assistant,” which can read uploaded estate planning documents and identify key provisions for use in estate planning analyses. Conceptually akin to Holistiplan's tool that reads tax returns to bring relevant information to the surface (as well as FP Alpha's, which performs similar functions for tax as well as estate planning and insurance documents), Ester has been further “trained” on the data that Wealth.com has accumulated as a provider of estate planning documents for both retail clients and clients of advisors, which the company purports will enable a much higher level of accuracy in its output than a more generalized AI tool like ChatGPT could provide. For advisors who do want to double-check Ester's work, its output shows not only the information it extracted from documents, but also guidance on its own estimate of accuracy, helping advisors jump even more quickly to the few spots where they might still want to review Ester's work.

The sensitivity to accuracy and validation is notable in a world of AI tools that are notorious for what often proves to be overconfidence about their output, which at times turns out to be inaccurate (or in some cases with ChatGPT, flat-out made-up). That itself has been one of the primary sticking points in getting advisors to adopt AI technology, since the perceived risk of handing over tasks like document review entirely to AI — when the advisor is still legally liable for any advice they give based on the tool's output — often outweighs the value of the time saved in doing so (especially if the advisor feels the need to constantly go back and check the tool's work). With Ester's validation function, the goal appears to be not only for advisors to hand off the process of document review to the technology, but also to make it easier to work with the technology to ensure accurate results while still being faster than reviewing the documents entirely manually.

Still, it remains to be seen whether tools like Ester or FP Alpha's Estate Module can reshape the estate planning technology landscape in the same way that Holistiplan did for tax planning. While there is theoretically value in a tool that can automatically scan documents to help advisors create value in the estate planning process, the reality may be that many clients simply don't demand or place as high a value on the advisor's role in estate planning as they do on tax planning. With the dramatic increase in the estate tax exemption over the last few decades, few clients have federal estate tax issues, and while all clients need some estate documents in place just to ensure the proper distribution of their assets, not all of them are willing to pay an advisor for additional help with the process on top of what they're already paying an attorney to prepare the documents — particularly as online services like LegalZoom make it cheaper and easier for clients to do it on their own.

To that end, given Wealth.com's core business as an estate planning document provider (drafting wills and trusts for advisors' clients at an affordable rate), it might make more sense to view Ester functionally as more of a discovery tool — providing a value-add for advisors to facilitate estate planning conversations with their clients, whom the advisor can then send to Wealth.com to get their new documents — than as a stand-alone piece of planning software. Viewed that way, Ester's (and Wealth.com's) primary competition is really other document preparation services like Trust & Will and EncorEstate, and not pure estate planning software tools like FP Alpha. Which means that ultimately, Wealth.com may not need to revolutionize the AdvisorTech space for Ester to be considered successful — instead, it only needs to attract enough extra clients via the advisors drafting clients' estate planning documents on the platform to justify the investment in its AI solution.

When artificial intelligence began to take off in the public's attention in late 2022 and early 2023 with the emergence of Large Language Model-based tools like ChatGPT, predictions for its impact on the financial advisory industry varied widely. Although few believed that AI would fully replace financial advisors, and still fewer predicted that it would have no impact whatsoever, the range of outcomes in between was wide open for debate.

Half a year later, the consensus — at least judging by the types of tools on the market for advisors that actually incorporate AI — seems to be that the most effective use for AI in its current state is as a writing aid, especially when the advisor needs to start filling in a blank slate. Which makes sense given how LLMs actually work: They aren't actually “intelligent” by any definition, but rather use their training data based on large swathes of human language to predict the next word in a string in response to a prompt entered by the user. Meanwhile, for humans (even those of us who write for a living), putting intelligible words on a blank page can be a frustrating challenge. Consequently, many of the AI-driven tools for advisors that have emerged in the last few months have been varying versions of a “calculator for words,” which can generate reasonably relevant raw text (e.g., for a client email, meeting notes, social media post, and so on) that the advisor can then finalize with their own personal touches … in less time than it would take to create the whole thing from scratch.

What's interesting to note, however, is that the majority of the recent AI-integrated tools have been built as extensions of already existing platforms rather than new stand-alone products, such as Orion integrating ChatGPT into its Redtail Speak texting solution or Pulse360 adding an AI Writer into its lineup of advisor productivity tools. On the one hand, the trend toward adding AI onto existing products may simply be because it's faster and easier to build a ChatGPT integration into an already existing tool than to build one out of whole cloth (and hence the former are the only ones that have been released yet while the latter may still be under development). On the other hand, it could also be because it's easier to sell advisors on an AI-driven solution when it's a part of a product that they already use (and hence have a baseline level of trust and familiarity with, and are already using each day to begin with) than it is when AI is the software's whole thing.

Whatever the answer, it's notable that Wealth Management GPT has, after a pilot period, recently launched one of the first stand-alone advisor-facing AI tools. Created by Marc Butler, the former president of Skience, Wealth Management GPT is at its core a writing and communication tool designed to aid advisors across a range of different use cases, including email writing, content creation (e.g., blog posts and client education), and client meeting materials. It offers a series of templates that the advisor can then further tailor to specific types of clients or even to the concerns of individual clients themselves.

For advisors, the debut of Wealth Management GPT reinforces the idea that the best purpose of the current generation of AI tools is not to generate planning analysis and advice, but rather to generate text based on the ideas that the advisor already has (or help the advisors to ideate what content might be of interest to their clients in the first place). Meanwhile, its position as a stand-alone tool allows AI-curious advisors to try out the idea of AI-generated text without committing to a specific type of third-party software.

The question going forward, however, is where a tool like Wealth Management GPT really fits into an advisor's tech stack (or not). It's great to have a tool that can generate emails, blog posts, meeting agendas and so on, but it isn't clear that advisors will want a single third-party tool for all of these, or want to have to log into a separate application to use them when it doesn't already exist where those functions already live (e.g., in the advisor's email provider, blog platform, or word processor). There are some indications that Wealth Management GPT will have the capability to integrate with other apps in the future, which would help tie together some of the pieces (particularly those that don't have their own internal AI capabilities), but the details at this point are extremely sparse — and ultimately, if enough of an advisor's technology tools do start to incorporate AI (of which the number is continuously increasing, to the extent that it might soon be harder to find a tool without AI than with it), it's unclear whether they'd want to pay for a stand-alone solution instead.

Still, at this relatively nascent stage of AI tools, it's a positive sign to see growth in the direction of independent tools that can tie together the parts of an advisor's tech stack that haven't yet incorporated AI, and as other categories of technology (like portfolio management) have shown, there are plenty of advisors on both sides of the divide between the "best-of-breed" (i.e., choosing the individual tools that work best for the advisor, and figuring out ways to make them work together) and "walled garden" approaches (i.e., using a single solution where everything works together seamlessly), and therefore ample room for tools that cater to either approach to flourish.

In the pre-internet days, if you wanted two pieces of software to be able to work together, they would have essentially needed to have been designed to cooperate from the start, which functionally meant they would have needed to come from the same manufacturer or suite of products, or be a proprietary custom build of the company using them. However, with the rise of the Internet — specifically, the rise of cloud-based software that lives online rather than on a company's own servers — the interconnectivity of APIs allowed for a much wider range of possibilities for software from different providers to send and receive data from each other..

In the advisory world, the end result was that advisors no longer needed to seek out all-in-one platforms that relied on a single database to perform all of their functions, or an advisor platform with its own proprietary tools to accomplish the same; instead, they could pick out individual “best-of-breed” solutions to solve for all of their various distinct needs, with APIs serving as the plumbing that allowed information to flow back and forth and allow the advisor to build workflows on top of multiple tools without needing to reenter the same data at every step.

The challenge, however, is that as technology tools for advisors continue to proliferate (with ever-more logos on the Kitces AdvisorTech Map!), the demands on APIs and integration capabilities grow exponentially as advisors increasingly rely on the ability for their software to work together. Each new tool creates an additional “node” in the network that needs to connect to some or all of the other nodes, and as the number of vendors increases, the number of point-to-point integrations grows multiplicatively, which also means the number of chances for those connections to break (or even just function less than ideally) increases in kind. It isn't coincidental, then, that as the array of tech solutions available to advisors has grown over the years, so too have advisors' frustrations with their tools' capabilities (or lack thereof) for integrating with one another.

Advisors' overall dissatisfaction with the integration of their tech stack was one of the themes explored in this year's Kitces Research AdvisorTech Study. The ongoing challenges with integration are perhaps best highlighted by the fact that, on a scale of 1 to 10, advisors on average rated their satisfaction with their entire tech stack lower (at 7.3) than their individual software tools within the tech stack (at 7.6). In other words, when looking at their technology infrastructure, advisors viewed the whole as worse than the sum of its parts!

Beyond the overall dissatisfaction around integration, some more nuanced trends emerge when looking deeper into the data. For instance, when asked directly about how well their technology tools integrate with each other, advisors who used 12 or fewer different tools rated their integrations the lowest (at 5.6 out of 10), while those using 18 or more tools rated their integrations the highest (at 6.4). If the simple explanation that more software tools leads to more integration struggles were true, one would expect the exact opposite; instead, however, it seems that advisors who are using lots of technology are actually more satisfied with their software's integration capabilities (perhaps because they're just generally more tech-savvy to begin with, as evidenced by the fact that they're using lots of technology), while those who are using the least technology (and conversely might be less tech-savvy overall) are struggling the most with integration.

In other words, it isn't just how well the software integrates that leads advisors to like or dislike their tools' integration capabilities, it's also the comfort level of the advisors themselves in figuring out how to make the integrations work (or conversely, a gap in how well the tools facilitate their own integrations and configuration without a lot of advisor effort). That to some extent means there will always be some advisors who will never be satisfied with their software's integration simply because they don't have a level of comfort with technology that predisposes them to figure out how to make the best use of it — but also means that tech providers could also put more focus on making their integrations easier, since a more intuitive process for setting up and actually using the integration might be enough to win over some of the less tech-savvy advisors who would otherwise struggle with putting it into practice on their own. (Though notably, given that even the advisors with the most comfort in technology only rated their software's integration at a 6.4 out of 10, there's still ample room for the integration itself to improve.)

Also on the topic of integration, the Kitces AdvisorTech survey data revealed that, despite broker-dealer and RIA custodial platforms investing heavily in integration capabilities in recent years to paint themselves as the “hub” of an advisor's business, few advisors actually see those platforms in that way. When asked what they consider the technology hub of their advisory firm, most advisors chose their CRM software, followed by financial planning software and portfolio management systems. In fact, only around 8% of advisors viewed their broker-dealer or custodial platform as the hub of their business — suggesting that the industry as a whole might not be building integrations in the way that advisors actually use them. On one hand, that might explain some of advisors' frustrations with integration (since if most of the investment is going toward integrations they don't frequently use, it follows that the ones they use most often are less likely to work the way they want them to); on the other hand, it demonstrates why tools like Salesforce become so popular once advisory firms reach a certain size and scale — since for more tech-savvy firms that have the resources to make the investment in it, Salesforce has the most capabilities to build and support a lot of integration, customized to the way the firm actually wants it to work (albeit at a material cost of configuration and implementation to do so, which larger firms are big enough to afford).

Ultimately, as the array of technology solutions grows in breadth and depth, the challenges in integrating multiple solutions certainly won't get any easier to resolve over time, with bigger and smaller firms (and more and less tech-savvy advisors) each encountering their own unique issues. Along with highlighting an opportunity for technology consultants who are knowledgeable about advisory firms and AdvisorTech who can help firms navigate the challenges of building and integrating their tech stack, the survey data also demonstrate an opportunity for software providers that can not only build integrations that work, but also make them work the way advisors want them to (and, on top of that, be easy to use).

The traditional way to build an advisory firm's tech stack is that as a firm grows and matures and has new needs come up, it adopts new technology to address those needs, which leads to an array of various components, some newer and some older, with each one chosen to address the firm's needs at the time it was adopted. This model has the advantage that each piece of technology was individually chosen to best meet the specific needs of the firm (at least at the time it was chosen); the disadvantage is that, with a tech stack made up of numerous disparate pieces — often each built by different providers — there's no guarantee that all of the pieces will work together well, and inevitably some of the gaps in integration will lead to inefficiencies like needing to enter the same client information into several different software platforms during the onboarding process.

This double-data-entry problem is annoying to advisory firm employees, which means that integration often ranks high on the list of AdvisorTech features that advisors find important to their business. In reality, however, the average advisory firm (according to the 2022 InvestmentNews Benchmarking Study) had a profit margin of 31% — up from 25% just five years earlier. That implies that tech-related inefficiency — even as new software tools and subsequent integration challenges proliferate each year — isn't exactly dragging down the bottom line of most firms. This makes sense, however, given that (1) client onboarding tends to be the most data entry-heavy process for most firms and (2) the latest 2023 Schwab Advisor Benchmarking study found the typical advisory firm only grew its client base at 6.2% per year (or no more than five to 10 new clients per advisor), and so ultimately there are only so many hours of onboarding data entry and new client service that could be saved by integration in the first place.

Still, as a firm scales up, it often does need to invest in technology that can work together, which explains the popularity of “all-in-one” platforms among midsize to large advisory firms that are designed to function as an integrated whole. The issue with this approach is that once a firm has “bought into” an all-in-one ecosystem, it's hard to venture back outside: It's not easy to justify the cost of any piece of outside software that duplicates something already included in the all-in-one platform, even if it would be a superior option. And so for firms that really care about a seamless integrated experience, but also want to make sure that every piece of software is the right one for them, the alternative might be to build an entire customized tech ecosystem in-house — with the obvious caveat that doing so requires a much bigger outlay of resources compared with using third-party technology, and thus is generally only an option for firms that have built up enough scale and revenue to support the massive cost of creating a custom tech infrastructure.

Or is it? The last few years have notably seen the launches of several RIA startups that have flipped the traditional tech stack pathway on its head. Rather than building an RIA firm and buying or building the tech as it scales up, “digitally native” RIAs have started by building a proprietary technology platform first, and then building — or buying — an RIA business on top of it. Such is the model followed by Farther Finance (founded in 2019), Alternativ (founded in 2021) and Savvy Wealth (also founded in 2021), each of which focused first on building the technology on which their RIA would be run (funded by venture capital investments to cover the intensive upfront development costs), only after which they began to recruit advisors — or in Alternativ's case, acquire an RIA of their own — and serve clients.

There's obvious appeal for an advisory firm to solve for the issues of technology and integration upfront. In addition to streamlining back-end processes like client onboarding and communications from the advisor's perspective (for which Savvy has launched a new AI-driven platform promising to automate many key advisor workflows), digitally native RIAs can design with the type of clean interface and ease of use that modern clients expect (and that not all of the industry's legacy providers have managed to keep pace with).

Despite those advantages, however, there are still questions about how much being digitally native is really worth to advisors and their clients. For advisors, affiliating with a digitally native RIA like Savvy or Farther involves either joining as a W-2 employee and receiving a payout as a percentage of revenue generated, or affiliating as a 1099 contractor and paying the firm a portion of the revenue earned — either of which effectively involves “paying” the RIA what often amounts to at least 10% to 20% of revenue in exchange for the use of their technology platform (along with investment management, marketing, back-office or other support the RIA might offer). By contrast, industry benchmarking studies show that on the whole, advisory firms spend only about 3% of their revenue on technology — which begs the question of whether it would be worth it to join a digitally native RIA at an additional cost of 7% to 17% of revenue when the average advisor is already earning profit margins of 31% on their own?

And from the client perspective, digitally native RIAs seem poised to relearn the lesson of (first direct-to-consumer and then B2B) robo-advisors in the 2010s: that a clean interface and one-click account opening simply aren’t enough to attract clients without the advisor having an effective marketing approach to bring them to the firm's website in the first place. In other words, advisors without effective lead generation can't expect to find it by affiliating with a digitally native RIA, and those with effective lead generation are likely producing enough new revenue to simply buy the technology tools they need to scale further, without paying a digitally native RIA to provide it for them.

The questions in the long run, then, are whether advisors will really be willing to pay a premium to affiliate with or work for the new crop of digitally native RIA startups to deliver an all-in-one proprietary tech solution, as well as whether those firms will be able to build out the marketing and lead generation structures needed to bring in clients and generate revenue — or alternatively, whether they'll need to raise more capital to acquire RIA firms (along with their advisors and assets) to join them. If that's the case, however, it's hard not to wonder whether they shouldn't have gone with the more traditional route of buying third-party software to begin with, and just concentrated their capital on client or advisor acquisition, rather than trying to “disrupt” an advisor technology landscape that perhaps wasn't as broken as it seems given typical RIA margins. Because if the economic reality is that if advisors aren't really being economically dragged down by their technology woes, then there's only so much they'll be willing to pay for solutions that purport to solve them.

Most financial advisors aren't in the business of administering trusts for their clients. In part, this is simply because the roots of trust administration are with trust companies, which evolved nearly a century ago from a state-based regulatory structure that was entirely distinct from that which grew up around financial advisors (who were regulated largely by state and federal securities agencies). In fact, historically it was illegal in many cases for an advisory firm to be the administrator of a client's trust — either (in the case of broker-dealer representatives) because it was an untenable conflict of interest to be selling products to a trust that the advisor also has fiduciary duty to, or (in the RIA model) because companies that managed investments within the trust had conflicts of interest if they were also the trustee who was also responsible for monitoring, hiring or firing the manager of the trust's assets (i.e., themselves).

As a result, advisory firm clients with trusts would generally have two options. Either they would work with bank trust companies — which often took the trusts out of the advisor's sphere entirely, since the banks typically had their own internal investment solutions developed under the state laws for trust companies — or the advisor could rely on their own networks of lawyers or accountants, who could oversee the trust and work with the advisor in an investment function (which, while being advantageous for the advisor, who was able to manage the trust assets, often meant the client paid a premium in fees in the form of the third-party professional's high hourly rates).

More recently, recognizing the issue of advisors struggling to find partners who could do trust administration at a reasonable cost but who wouldn't interfere with the advisor's ability to manage the trust assets, there has been an emergence of more advisor-friendly independent trust companies (including BOK Financial, Wealth Advisors Trust Co., Capital First, Independent Trust Co. and the advisor-owned National Advisors Trust Co.) which offer services purely focused around trust administration and, while occasionally offering asset management for those who need it, generally don't compete with advisors for their business.

Against this backdrop, two recent AdvisorTech startups, Valur and Luminary, are aiming to further evolve the relationship between financial advisors and trust administration. Both platforms seek to engender a more active role for advisors in trust planning and administration, starting with trust and estate planning and visualization tools that advisors can use to model and present trust scenarios and recommendation, and going on to provide key tools for the ongoing management of the trust. Notably, the two tools diverge in the ongoing services they provide — Valur is more of a pure trust company that provides trust document preparation, administration and accounting, while Luminary, which provides monitoring and reporting tools along with workflow management around different members of the trust team, still requires a third-party trustee. But the idea around both is to keep the advisor at the center of the relationship with the client and their trust, from the early planning stages to the ongoing management (which given the legacy planning nature of many trusts, is often a years- or decades-long relationship).

The question remains, however, how active of a role advisors will really want to take in their clients' trust administration beyond the initial planning and ongoing investment management. In addition to the issue of whether being too actively involved in creating and administering trusts opens up liability and conflict-of-interest concerns, the reality is that most advisors aren't compensated anything extra for ongoing trust oversight, opening up the risk of scope creep when an advisor signs up for a tool that effectively obligates them to provide ongoing monitoring for clients' trusts. On the other hand, however, a more technology-enabled approach to trust administration like Valur's, which operates at a lower cost than the typical traditional trust administrators, could also potentially bring some estate planning strategies down-market (e.g., enabling charitable remainder trusts for clients with under $500,000 in assets, which previously would not have been feasible given the costs of setup and administration), opening up new markets for advisors to plan and manage those strategies on an ongoing basis.

Ultimately, given that advisor-friendly trust companies historically have been few and far between, and the still nontrivial costs it takes to set up and then administer trusts on an ongoing basis, the emergence of new, tech-savvy (and ostensibly lower-cost through the use of that technology) trust and estate planning solutions that can make it easier to recommend a trust administrator (without relying on the local high-hourly-rate attorney) is welcome. However, it remains to be seen (with fewer clients than ever being subject to estate taxes and thus reduced demand for many kinds of trusts) whether these solutions create enough of a business opportunity for advisors to make them worth adopting.

Generally, financial advisors use social media in three different ways:

In the early 2010s, what had been a scattered early landscape of social media networks coalesced into a fairly stable Big 3 of social media platforms that has endured up to the present day: LinkedIn, Facebook (and its sub-properties like Instagram), and Twitter. Curiously, each of those platforms did a good job of fulfilling two of the three functions above: LinkedIn, with its professional emphasis, was best suited to marketing and networking; Facebook, which focuses on news and personal connections, became best for entertainment and marketing; and Twitter, with its effective threading and commenting functions, was best for networking and entertainment. In the intervening years, faddy networks like Vine and Clubhouse have come and gone, and even more enduring additions like Instagram and TikTok have come and stayed, and yet none quite had the staying power of the LinkedIn-Facebook-Twitter trio, at least among advisors.

From the consumer perspective, social media networks build staying power with their ”network effects” — at some point, certain platforms are the place to be because "everyone else" is there too, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. From the advisor perspective, an added benefit of those networks' endurance is that they've all been around and commonly used for long enough to be embedded into many social media archiving platforms for compliance purposes. Because no matter which of the above purposes an advisor uses social media for, it's all big-A Advertisement from the perspective of state and federal securities regulators, as long as there is any marketing component at all. That makes trying out new platforms a struggle when they haven't yet been added by social media archiving tools for advisors (which may themselves not be eager to put resources toward platforms that could prove to be fads and vanish, and might be constrained anyway by a lack of API capabilities in newer platforms that would allow them to archive advisors' posts in the first place). That essentially leads to an amplified version of the traditional network effect of social media, where most advisors are on the same three platforms because that's what their compliance capabilities will allow, which leads more advisors to join those networks (because that's where the other advisors are), which leads compliance technology to continue to focus their energies on those same platforms, and so on down the rabbit hole.

Against this backdrop, the decline of Twitter (or as it now calls itself, X) under Elon Musk's ownership — which includes losses in functionality and notable upticks in bot and spam accounts — has coincided with a slew of users leaving the platform, while its reported financial woes raise the possibility that Twitter may not even survive much longer for those who remain. All of which has left many in the proverbial #FinTwit community wondering whether a new alternative platform will come around that can replicate the functions that Twitter once served (which startups BlueSky, Mastodon and Meta/Facebook's Threads are all positioning themselves to do, though none has found significant traction so far). However, the catch-22 advisors face is that there isn't likely to be a significant advisor community on any platform that can't be archived by current compliance technology, while compliance technology platforms (and firm compliance departments) may be hesitant to embrace any network that doesn't already have a significant number of advisors on it. Not to mention that it isn't at all clear at this point which (if any) of these platforms will ultimately be worth the time the advisor may put into it, which is really a function of how many other advisors (and potential clients) also decide to show up.

Instead, it seems more likely that, rather than migrate to a new competitor like Threads, advisors will consolidate their adoption around where they already have deep foundations — LinkedIn and Facebook — meaning that the social media Big 3 could soon be just the Big 2. In the big picture for advisor social media, that might not be that big of a deal: Twitter has generally ranked a distant third behind LinkedIn and Facebook in adoption among advisors anyway (as shown in both Putnam's 2023 survey of advisors' use of social media and the 2022 Kitces Research study on financial advisor marketing), with usage declining steeply even before Musk's takeover. Furthermore, the three key uses of social media listed above — marketing, networking, and entertainment — are all handled adequately by the combination of LinkedIn and Facebook, while other platforms that could be used to make up for the entertainment function (that Twitter admittedly fulfilled in a unique way) can generally be used without a compliance archiving solution, provided that the advisor doesn't also use them to promote their services.

In the end, then, it may not be so problematic if Twitter drops off the Big 3 list without a replacement since in reality, most advisors can be found on the other two networks, while the broader exodus (X-odus?) from Twitter means that advisors continuing to look for clients there would find themselves fishing in increasingly sparse waters anyway. Meanwhile, the resurgence of newsletters and blogs stemming from the rise of Substack and Ghost, along with the proliferation of choices among (non-advisory-related) social media platforms that in a way echoes the pre-Big-3 era of the early and mid-aughts, means that there will never be a lack of options for entertainment.

In the meantime, we’ve rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map (produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group)!

So what do you think? Is estate planning document review a big enough pain point to pay for an AI solution to read and summarize them for you? Do software integration issues cause a meaningful drag in productivity to the extent that a seamless solution would be worth paying a percentage of revenue? Where will you be spending your free time if Twitter joins Friendster and Google+ in the dustbin of social media history?

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter @MichaelKitces.

Ben Henry-Moreland is senior financial planning nerd at Kitces.com, where he researches and writes for the Nerd’s Eye View blog. In addition to his work at Kitces.com, Ben serves clients at his RIA firm, Freelance Financial Planning.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound