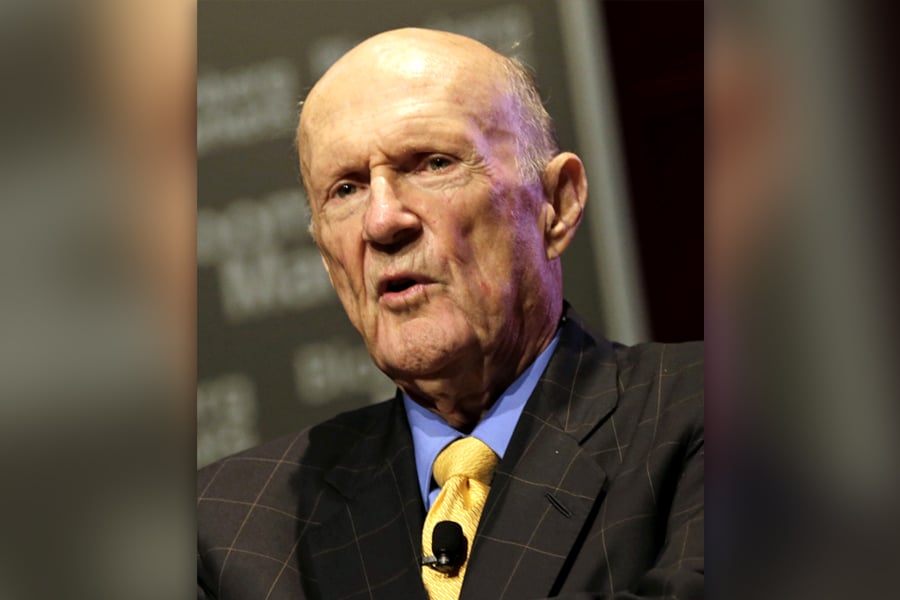

Julian Robertson, the billionaire Tiger Management founder who became one of his generation’s most successful hedge fund managers and a mentor to a wave of investors known as Tiger Cubs, has died. He was 90.

He died at his home in Manhattan from cardiac complications, according to Fraser Seitel, a longtime spokesman for Robertson.

The North Carolina-born investor started New York-based Tiger Management in 1980 with $8.8 million. He was 48 at the time, relatively old to be launching his own firm. By mid-1998, its assets had soared to about $22 billion on the back of annual returns averaging 32%, earning him a reputation on par with those of industry peers George Soros and Michael Steinhardt.

“If I had had to give my own money to any of them, I would have given it to Robertson,” investor Jim Chanos said in an interview for “More Money Than God,” a 2010 book on hedge funds by Sebastian Mallaby. “I knew that he knew stocks better than anyone.”

Robertson had an estimated net worth of $4 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Known for his strength of personality and extensive network of advisers, Robertson instilled in his traders his keys to success, Mallaby wrote. They included managing holdings aggressively, removing good companies to make room for better ones, not risking more than 5% of capital on one bet and keeping the faith through bad times.

Robertson, who had started out primarily as a stock picker, began ramping up bets in bonds and foreign exchange in the 1990s, veering into the territory of macro fund managers, so called because they wager on macroeconomic trends that drive fluctuations in interest rates and currencies.

A wrong-way bet on the yen in 1998 sent investors fleeing from Tiger. In March 2000, Robertson announced that he was closing his six Tiger funds, after watching assets dwindle to $6 billion from $21 billion in 18 months because of losses and investor withdrawals.

“There is no point in subjecting our investors to risk in a market which I frankly do not understand,” he wrote in a letter to investors. “We have seen manic periods like this before and I remain confident that despite the current disfavor in which it is held, value investing remains the best course.”

Robertson’s firm spawned dozens of “cubs” — former employees who learned the trade at Tiger before branching out on their own. His alumni formed a new generation of star investors, including Chase Coleman, John Griffin, Lee Ainslie, Andreas Halvorsen and Stephen Mandel. After Robertson closed down Tiger, he also seeded many young managers, giving them capital in exchange for a share of their profits.

The cubs are mostly stock pickers in Robertson’s mold, relying on research to identify companies they deem inexpensive based on financial yardsticks such as earnings growth, and to bet against stocks they think are poised to fall. They pay special attention to the quality of company management.

“The true success of Robertson and Tiger extends beyond the stellar performance numbers and mind-boggling assets under management,” Daniel A. Strachman wrote in “Julian Robertson: A Tiger in the Land of Bulls and Bears,” his 2004 book. “Ultimately, the success of the firm can be measured in the legacy of his cubs.”

One of Robertson’s Tiger Cub disciples triggered one of modern capitalism’s biggest blowups.

Bill Hwang left Robertson’s firm to form Tiger Asia Management, which pleaded guilty to insider trading on Chinese bank stocks in 2012, agreeing to criminal and civil settlements of more than $60 million. Hwang then turned to managing his own money, through a family office he called Archegos Capital Management. That firm lost about $20 billion in two days in March 2021, rocking global finance and costing global banks billions in losses.

Unlike Robertson, Hwang had flown under the radar, secretly making one of Wall Street’s biggest fortunes before losing it so publicly.

“I’m just very sad about it,” Robertson said in an interview shortly after the Archegos blowup. “I’m a great fan of Bill, and it could probably happen to anyone. But I’m sorry it happened to Bill.”

Julian Hart Robertson Jr. was born on June 25, 1932, in Salisbury, North Carolina. His father, Julian Hart Robertson, was a businessman in the textile industry. His mother was the former Blanche Spencer.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in business from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill before spending two years in the U.S. Navy. Robertson joined Kidder Peabody & Co. in 1957, rising through the ranks to eventually become chief executive of Webster Management Corp., Kidder Peabody’s asset management arm, in 1974.

Robertson “was like a sponge, constantly soaking up as much information as he could from his colleagues, peers and competitors,” Strachman wrote. “His skill was learning from others and taking the knowledge and turning it into profits for the firm, his colleagues, his clients and, of course, himself.”

One of those he learned from directly, according to Strachman, was Alfred Winslow Jones, who was the father-in-law of a colleague. The founder of A.W. Jones & Co., Jones is regarded as the intellectual father of the hedge (or “hedged”) fund, meaning one that placed bets on the market falling as well as rising.

In 1978, Robertson and his wife, Josie, moved to New Zealand, where he planned to write a novel. After six months, he concluded that he was better at investing than he was at writing and returned to New York, where he founded Tiger Management with a former Kidder Peabody colleague, Thorpe McKenzie. (McKenzie departed Tiger in 1982.)

The Tiger name, Strachman wrote, was inspired by Robertson’s habit of calling people “Tiger” if he couldn’t remember their name. By 1991, the firm managed $1 billion in assets.

In addition to his hedge fund career, Robertson ran the Tiger Foundation to support low-income New Yorkers and their families. Since its inception in 1989, it has provided more than $250 million in grants to help schools, employment training programs and childhood education, according to its website.

After closing his hedge fund, Robertson transformed Tiger Management into a firm that seeded many young managers, giving them capital in exchange for a share of their profits. He was through with the stressful job of managing client money.

“I didn’t want my obituary to be, ‘He died getting a quote on the yen,’” Robertson said in a 2013 interview with the Australian Financial Review.

Spending part of each year in New Zealand, Robertson owned wineries as well as several golf resorts in the South Pacific nation.

Robertson’s wife, the former Josephine Tucker, who was known as Josie, died of breast cancer in 2010. They had three sons: Julian III, known as Jay, who managed his father’s properties in New Zealand; Alexander, who became president of Tiger’s seeding business; and Spencer, who worked at the Tiger Foundation before founding Pave charter schools.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound