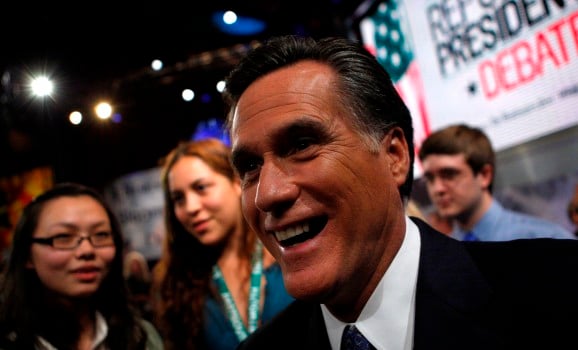

Candidate's tax revelation casts unflattering light on shadowy world of private equity; 'crazy not to bring it up'

Mitt Romney's campaign for the Republican presidential nomination may be costing his private-equity backers a lot more than they bargained for.

Attacks by opponents portraying Bain Capital LLC, Romney and other buyout managers as corporate looters who enrich themselves at the expense of ordinary workers have put a spotlight on the industry that will affect negotiations about future investments, according to officials and trustees at public pensions. As firms struggle to raise funds, pensions may be more reluctant to commit money and may ask for more details on job creation and push for lower fees, these officials said.

“Private-equity managers' wealth and tax rates are on display at a time when pensions are getting squeezed,” said Joseph Alejandro, treasurer of the New York City Patrolmen's Benevolent Association. “Public investors should raise questions about whether the business is overly generous for managers. I hope the renewed attention on the industry will lead to discussions on fees and greater controls like claw-backs.”

The debate is affecting private-equity managers, including Romney's former firm, Boston-based Bain Capital, as they're competing for a shrinking pool of investor dollars. Fundraising slowed in the third quarter to the weakest pace since before the global financial crisis and stayed near that level in the final three months of the year, according to London-based researcher Preqin Ltd.

Political Attacks

U.S. public and private pensions provide 42 percent of the capital for all private-equity investments, according to the Private Equity Growth Capital Council in Washington. Public pensions are sensitive to protracted debates about managers' compensation and whether buyouts create value and jobs, because they must answer to ordinary workers, said one official, who asked not to be named because he wasn't authorized to speak on the topic.

“The political attacks against Romney and Bain will definitely come up when firms pitch us their new funds,” said William Atwood, executive director of the Illinois State Board of Investment, which oversees $10.4 billion in pension funds. “You'd be crazy not to bring it up.”

The pension board had $621.3 million, or 6 percent of its assets, in private equity as of Dec. 31, according to its website.

Private-equity firms typically charge about 1.5 percent of assets to cover their expenses, and 20 percent of the profits from investments as compensation, or carried interest.

Institutional Investor Push

Pensions, endowments and sovereign-wealth funds, which comprise the majority of so-called limited partners in buyout funds, have pressed for better payouts and data from global private-equity managers in the wake of the financial crisis. Some of the biggest investors formed the Toronto-based Institutional Limited Partners Association, which introduced guidelines in 2009 addressing fees, governance and communication with clients. Blackstone Group LP (BX), KKR & Co. and TPG Capital are among firms that have signed on.

In addition to the fees, which eat into returns for pensioners, private-equity managers have also been criticized for paying a lower tax rate on much of their income than ordinary wage earners. Carried interest is taxed at the lower, 15 percent rate for capital gains, rather than the 35 percent top rate that applies to regular income.

Gogel Sees Change

Donald Gogel, head of Clayton Dubilier & Rice LLC, said today he would accept changes to the carried-interest tax rate. The spotlight shed on that issue by Romney's campaign may lead to changes to the U.S. tax code, Gogel said in an interview with Bloomberg Television's Erik Schatzker at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

“I would like to see a progressive system that is far more simple,” Gogel said in the interview. The tax code “is not very efficient or fair across the board.”

Two-thirds of investors surveyed in the Bloomberg Global Poll say the tax break for carried interest isn't warranted.

Buyout profits and their tax treatment helped make buyout pioneers such as Stephen Schwarzman, co-founder of Blackstone and a supporter of Romney's campaign, some of the richest Americans. Schwarzman, ranked the 66th-richest American by Forbes, held a fundraiser for Romney at his Park Avenue apartment on Dec. 14. He has opposed raising the tax on carried interest and endorsed a flat tax as part of comprehensive reform of the U.S. tax code.

Punishing Blackstone

U.S. pensions account for about 27 percent of assets at one of Blackstone's largest funds, compared with 30 percent and 31 percent for comparable funds at Washington-based Carlyle Group LP and New York's KKR (KKR), according to Preqin estimates based on the investors it tracks. Their influence was on display last year, when Blackstone lost out on a deal to manage hedge-fund investments for New York City's public pensions after the firm's chief strategist suggested retiree benefits were too generous.

Buyout funds globally are seeking to raise about $165 billion, more than in 2006 at the height of the fundraising boom. KKR, Warburg Pincus LLC and Providence Equity Partners LLC are garnering commitments.

Carlyle Group, which is preparing an initial public offering, and Silver Lake Management LLC are set to begin marketing funds, according to people familiar with the plans.

Search for Yield

Institutional investors stung by the financial crisis have been slow to commit to new buyout funds, which raised almost $214 billion in the second quarter of 2007, at the peak of the leveraged-buyout boom. Industrywide, firms raised $52.4 billion for 108 funds during the fourth quarter.

Bain, which late last year started gauging investor interest for a new buyout fund, relied on pensions for about 9 percent of client assets in a recent fund. The firm has traditionally raised most of its capital from foundations, endowments, family offices and wealthy individuals.

Alex Stanton, a spokesman for Bain Capital, declined to comment.

When Romney set out to raise Bain's first fund in 1984, he steered clear of pension funds, pursuing ultra-high net worth individuals who contributed about $37 million to form the fund, according to a person who worked with Romney at the time. KKR's co-founders, by contrast, received early capital from Oregon's and Washington's pensions, with the latter contributing $12 million to KKR's first fund in 1982.

Bain's Returns

The success of Bain's first fund, which generated a 61 percent average annual return, according to marketing documents from 2004 obtained by Bloomberg News, helped attract other investors who wanted to share in the profits and allowed Bain to charge a premium for its investment services. The firm collects 30 percent of the profits it earns on its investments, the highest in the industry. Pensions historically have been less willing to pay Bain the higher performance fees.

With Romney keeping the spotlight on Bain, public plans may be reticent to invest now because of the controversy, said Heather L. Slavkin, senior legal and policy adviser for the office of investment at AFL-CIO, the nation's largest union federation.

“Trustees are concerned about headline risk and there's a headline on Bain every day,” said Slavkin, whose office advocates for the security of $480 billion of union-sponsored pensions. “Nobody wants their decisions under a microscope and trustees are no different. They don't want to see their decisions questioned publicly.”

‘Heads Down'

For their part, many firms say the firestorm will blow over and pensions will come to rely more on private equity to meet their growing obligations to workers because traditional assets like stocks and bonds won't return enough.

The Federal Reserve this month said it would keep interest rates low through 2014, driving investors into higher-yielding assets and pushing down borrowing costs for leveraged buyouts.

Bain Capital Managing Director Stephen Pagliuca, also speaking in Davos, said investors will stick with the firm and criticism of the private-equity industry will pass.

“Our limited partners have been with us for 28 years many of them,” he said in an interview with Erik Schatzker. “We just keep our heads down and try to build value.”

Romney's Taxes

Under pressure from rivals, Romney, whose wealth is estimated at between $190 million and $250 million by his campaign, this month disclosed tax returns showing he paid a 13.9 percent tax rate in 2010 on income of $21.6 million.

Representative Sander Levin of Michigan, the top Democrat on the House Ways and Means Committee, said on Jan. 18 that he plans to reintroduce legislation that would tax carried interest at ordinary income rates.

Schwarzman, who said four months ago that he pays an effective personal income tax rate of 53 percent, has been less forthcoming. Blackstone, the world's biggest private-equity firm, is reducing its voting rights in BankUnited Inc (BKU). by converting some shares so that Schwarzman doesn't have to disclose his financial information to the U.S. Federal Reserve, a person familiar with the plans said earlier this month.

Peter Rose, a spokesman for Blackstone, declined to comment.

To mitigate the damage to private equity's image, the industry's lobbying group is starting a campaign to showcase its members' contributions to the American economy, using testimonials of people who say private equity has helped their businesses grow. David Rubenstein, Carlyle's co-founder, said Romney shouldn't be criticized for the taxes he pays lawfully.

Still, said Atwood at the Illinois pension, the industry has little choice but to wait for an end of the attacks.

“We all know that private-equity managers make a lot of money and we know how they do their business, but when it's on the front page it causes us to think twice when making investment decisions,” Atwood said. “Private equity is more lucrative when it's kept quiet.”

--Bloomberg News