For someone who really doesn't like the concept of

smart beta, DoubleLine Capital LP portfolio manager Jeffrey Sherman sure has nailed the strategy.

The 17-month-old

DoubleLine Shiller Enhanced CAPE Fund (DSENX), which Mr. Sherman co-manages with chief executive Jeffrey Gundlach, has been leaving most of the large-cap value fund category in the dust by employing a strategy that seems to tap every performance and yield access point.

The fund's 3.4% advance since the start of the year compares to 0.99% for the large-cap value category, as tracked by Morningstar Inc., and 1.69% for the S&P 500 Index.

The fund, which has grown to an impressive $383 million, has a 12-month trailing return of 18.9%, compared with 9.76% for the category, and 14.74% for the S&P.

Last year, its first full calendar year in operation, the fund gained 17.7%, while the category averaged 10.21%, and the S&P climbed 13.69%.

Unfortunately, the fund is too new to hit most financial advisers' mutual fund screens.

TWO SOURCES OF RETURN

Mr. Sherman attributes the impressive performance to a strategy he describes as a “portfolio with two distinct return sources.”

That means, basically, equity and fixed income.

The equity side is where the smart beta comes in, a term Mr. Sherman will begrudgingly use because it has become a common phrase people are starting to understand.

“There is no true definition of smart beta, aside from it being any systematic rules-based strategy that does not use price or market capitalization as a basis for the index,” he said.

The fund is DoubleLine's first move into the smart beta world, and it has been done in a way one might expect from a company with DoubleLine's reputation for pushing the envelope.

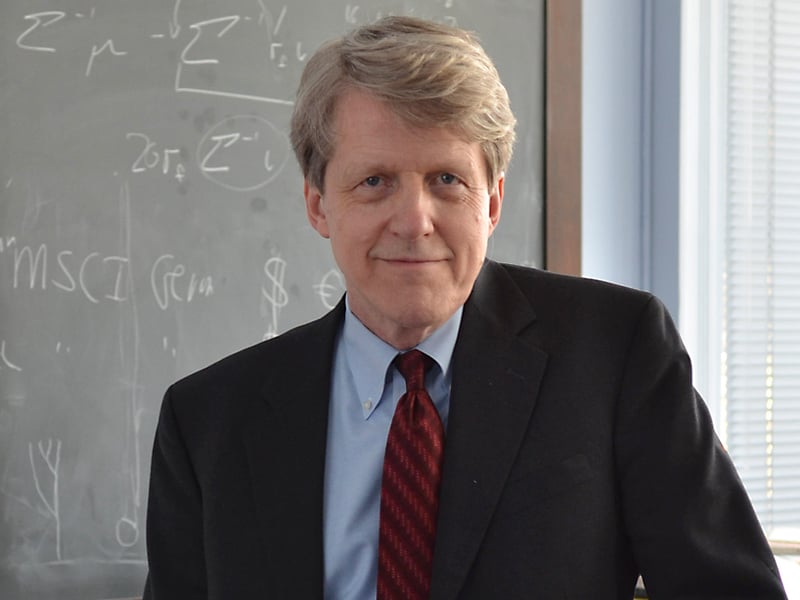

The equity side of the portfolio tracks the

Shiller Barclay's CAPE U.S. Sector Total Return Index, which is built around Yale University economics professor and Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller's cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio.

The index invests equally in the four most undervalued U.S. stock sectors based on their CAPE ratio and price momentum.

“The idea is that bubbles form and burst, and you can't predict exactly when that will happen,” Mr. Shiller said.

100-YEAR-OLD CONCEPT

In terms of why it has taken so long for a mutual fund to employ a strategy that can trace its origins in some form back at least 100 years, Mr. Shiller pointed to “conservatism in finance.”

“The [investing] public is just generally very skeptical and lacks a willingness to move to new ideas when it comes to finance,” he said.

Mr. Sherman, who only half-jokingly promotes a preferred moniker of “smart alpha” for the fund's overall strategy, explains that systematic, rules-based equity exposure is part of a “dual value proposition” that begins with a foundation in fixed income that investors might not expect from a fund hanging out in the large-cap value category.

Because the equity exposure is gained through swaps that are paid for as part of the fund's ongoing expense, every dollar that comes into the fund first lands in a diversified bond portfolio that is targeting an annual yield of 2.5%. That ongoing expense is 90 basis points, which is low for a smart beta mutual fund but more expensive than the average smart beta exchange-traded fund.

“The index is the smart beta part, but since we don't have to put any capital up front to enter the swaps, we might as well do something with that capital,” Mr. Sherman said. “It is a multi-sector approach to fixed income, with short to intermediate duration, that right now has a 3% yield, 1.6-year average duration.”

He explained that the fixed-income side of the portfolio is rooted in what DoubleLine does across its various multi-sector portfolios, but said the fund shouldn't be confused or compared with a balanced strategy, because almost all of the risk is still coming from the equity exposure.

“The fixed-income side is absolute-return-focused and it bleeds through to the portfolio's total return; that's why I'm calling it smart alpha,” Mr. Sherman said. “While you're waiting for returns to kick in from the equity side, why not generate some alpha by allocating across virtually every part of the fixed-income market?”