The global agreement reached at the United Nations’ COP26 summit in Glasgow last weekend may help solve one of the trickiest problems in climate policy: how to boost confidence in the voluntary market for carbon credits.

Such credits, or offsets, allow companies to pollute at home in exchange for investing in greener projects elsewhere. Voluntary markets are currently something of a Wild West, with no unified standards or governance — and experts say that at least some of the credits they generate do little or nothing to curb climate change.

“The voluntary market is really booming, but at the same time you have this integrity problem,” said Lambert Schneider, research coordinator on international carbon policy at the Oeko-Institut think tank in Germany. Although the COP26 agreement doesn’t directly affect voluntary markets, its rules may “spill over into the system, setting the bar higher.”

In Glasgow, after a six-year deadlock, negotiators agreed on rules on international emissions trading and established a UN-controlled marketplace. The new offset program will run in parallel to the existing voluntary markets.

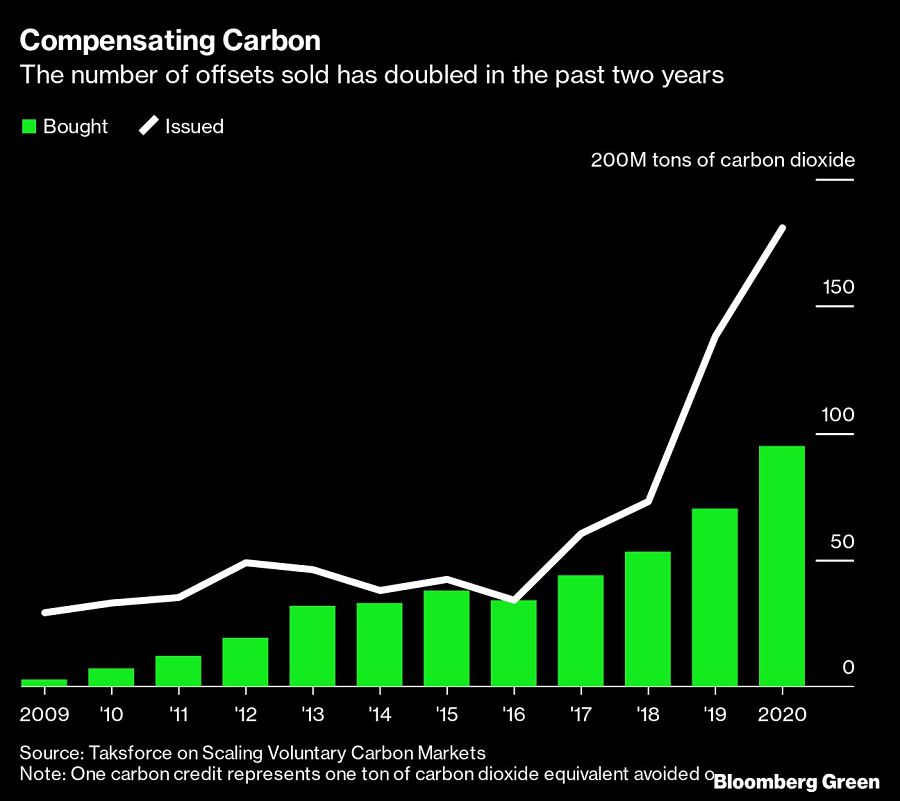

Demand for offsets is soaring. More credits were traded in the first eight months of this year than in all of 2020, according to BloombergNEF, as companies and governments spend billions of dollars to meet net-zero emissions targets and burnish their green credentials.

The offset market could be worth $100 billion by the end of the decade, up from about $300 million in 2018, according to projections by Mark Carney, a former Bank of England governor, and Bill Winters, the chief executive of Standard Chartered Plc. The two financial veterans last year created a task force including hundreds of business leaders, bankers, scientists and others to set up unified rules for voluntary markets.

But there are concerns. With little oversight in voluntary markets, there is room for abuse. Low-quality offsets, or emissions reductions counted twice, do little for the planet — and can even hinder the fight against climate change.

“The voluntary carbon market has a quality problem on the supply side,” said Schneider, who is also a co-chair of the expert panel on the task force. “There are some good projects, but there are also some projects that do not deliver actual emissions reductions.” He said there should also be “more transparency” surrounding demand for offsets.

The COP26 deal on carbon markets last weekend was a “powerful boost” in confidence for private investors, according to the International Emissions Trading Association. The challenge now is in the interpretation of the agreement and what it could mean for voluntary carbon markets.

For example, the Glasgow decision allows — but does not oblige — countries that host offset-generating projects to authorize credits for use toward climate targets abroad. Such authorization would ensure that the same emissions-reduction unit won’t be claimed twice: by the nation where the offsets were generated and by the company that bought them.

Credits that will be used for international programs, such as the offsetting system for airlines, will need authorization. Such a procedure isn’t currently required in voluntary markets.

Andrea Bonzanni, IETA’s international policy director, believes it will still be possible for a company to issue credits claiming emission cuts without authorization. Yet buyers may prefer authorized credits, which then can be used toward climate pledges.

“There are different views on where the market will head to, and this is normal,” Bonzanni said. The Glasgow deal “is a starting point for the private sector to keep delivering high-quality credits and functioning market.”

In the coming years, the UN credits could become a kind of global benchmark, with other voluntary carbon credit prices trading in relation, according to Henrik Hasselknippe, who’s in charge of carbon exchanges at Xpansiv, where more than 100 million metric tons of the credits have traded this year.

“Markets can handle multiple standards,” Hasselknippe said. “That’s something that we see in many markets.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound