The December edition kicks off with the big news that Halo Investing has raised a $100 million Series C round to fuel the ongoing growth of structured notes, annuities, buffered ETFs and other “protective” investment vehicles, alongside competitors Simon Markets and Luma, as high valuations and diminished forward-return expectations for stocks lead financial advisers to more proactively hedge client portfolios against a potential market decline. That mirrors a similar trend in the rise of alternative investment platforms as below-average expected returns on fixed income are leading advisers to find nontraditional alternatives for their bond allocations as well!

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting adviser technology announcements, including:

• Geowealth raises a $19 million Series B as a next-generation tech-savvy platform TAMP competitor.

• Orion acquires BasisCode Compliance to expand its compliance capabilities (as a pathway into larger enterprises?).

• Skience rolls out new integrations with Redtail as the CRM overlay business expands beyond just Salesforce.

• TIFIN Group raises another $47 million Series C round in an attempt to make the whole worth more than the sum of its variously acquired parts.

• FeeX partners with Advyzon as advisers continue to adopt tools to expand from AUM to the AUA model.

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in adviser technology, including:

• FP Alpha launches a new prospecting tool to help advisers find new planning opportunities more quickly.

• Helios Estate Planning announces that it’s shutting down as advisers continue to de-emphasize estate planning.

• Vestwell expands into state-sponsored auto-IRAs and 529 plans as it broadens its offering for advisers serving small-business owners.

•CapGainsValet and BlackRock’s Tax Evaluator ramp up with fresh data for end-of-year capital gains distributions from mutual funds (and some ETFs!).

Be sure to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map as well!

AdviserTech companies that want their tech announcements considered for future issues should submit to TechNews@kitces.com!

Notwithstanding the remarkably good returns for the typical client portfolio over the past decade of bull market returns, most financial advisers face significant pressure when it comes to the modern design of client portfolios.

On the one hand, near-zero yields on bonds — or at least, bond yields that in many cases are similarly lower than the fees that advisers charge to manage those bonds — are driving advisers to seek non-bond “alternatives” in the hopes of improving on fixed-income returns. In recent years, that’s led to the explosive growth of a number of major alternatives platforms.

On the other hand, elevated valuations for the overall stock market are leading to a litany of projections that equities, too, will produce below-average returns in the decade to come, coupled with an increased risk of a major bear market for stocks. That in recent years is driving explosive growth in structured notes and annuities and similar protective risk-managed investment vehicles.

The end result has been a series of eye-popping capital raises for platforms that are managing to solve for either fixed-income alternatives (e.g., iCapital and CAIS) or risk-managed equity alternatives (e.g., Simon, Luma, and Halo Investing). The latest news is that Halo Investing has raised a massive $100 million Series C round to continue to scale its distribution of structured notes, annuities and buffered ETFs.

The challenge, though, is that historically annuities have been a four-letter word for RIAs (many of whom left the insurance and broker-dealer world specifically to get away from annuity-centric product pushing). Structured products have faced even more of an uphill battle as a very complicated four-letter-word, a result of both their opacity when it comes to pricing, limitations on access (e.g., high investment minimums), and a handful of advisers who experimented with structured notes back in the 2000s only to have them blow up in the financial crisis because they were written on Lehman paper.

Nonetheless, the evolution of technology over the past decade has made structured notes increasingly accessible and increasingly transparent with respect to their pricing, allowing firms like Halo to democratize structured notes for a wider base of advisers far beyond the base of wirehouse brokers who sold them in the past.

Now, with a fresh round of $100 million, Halo ostensibly has all of the money it needs to spend its way to massive growth, either via acquisition to consolidate competing structured note providers, or via new/more distribution channels. And the size of the round implies that it has been able to develop a very repeatable go-to-market strategy (up 550% in 2020 alone!?) and found a way to make its messaging resonate with at least a subset of advisers who are concerned about investing client assets into a high-P/E stock market.

As long as bond yields remain so low and equity valuations so high, it’s hard to see how the growth of alternatives as a fixed-income substitute, and structured notes and annuities as an equity substitute, won’t continue to grow further from here?

Turnkey asset management platforms first emerged in the 1990s as financial advisers began to shift away from selling one-off mutual funds and toward creating diversified asset-allocated portfolios, where there was little sense in having each adviser spend the time to create and implement their own portfolios for clients when instead a centralized platform could establish a standard set of high-quality models and implement them for a large number of advisers at once on an outsourced basis. The pitch goes something like this: “Advisers don’t have the same resources that large asset managers do to build great portfolios, and while they may enjoy building the portfolios, they often aren’t really as good at it as Vanguard, BlackRock or American Funds. They should outsource that into models (or SMAs or UMAs) and focus on adding value in planning and building relationships with clients. Advisers can serve more clients if they outsource.”

In the 2000s, though, an alternative approach to outsourcing investment management emerged: the separately managed account, where a third-party asset manager could implement trades on behalf of a large number of advisers and their clients as well. The distinction, though, was that TAMPs typically provided the entire investment offering — from the investment management itself to the back-office operations staff and support, and the technology that was needed to track and report out the results to clients — while SMAs were more often just investment managers that had access to implement trades on behalf of advisers while the adviser was still responsible for running the advisory business itself (including their own staff and technology).

Yet over the past two decades, the two channels have increasingly converged, as SMAs were increasingly distributed through the technology platforms that enabled them (e.g., Envestnet), while TAMPs increasingly became technology-driven outsourced investment solutions (if only because the technology made the TAMP more efficient, while also improving the user experience for the adviser and their client). Today, SMA platforms often include TAMP providers, and TAMPs increasingly offer a widening range of SMAs and third-party models in their TAMP marketplace (all facilitated by their TAMP technology).

In this context, it’s notable that in November, Geowealth raised a whopping $19 million Series B round to continue its ongoing growth as an emerging TAMP (with a very respectable $7 billion-plus of AUM on the platform). Geowealth is somewhat unique in the TAMP world, though, as the provider has largely built its own technology from the ground up, from portfolio accounting and performance reporting, to proposal generation and billing and a client portal, and it’s now using that technology as the foundation to offer a wide range of investment solutions, from Geowealth’s own investment strategies, to a third-party model marketplace and even the ability to use Geowealth’s technology for advisers to implement their own model portfolios.

From that perspective, though, Geowealth arguably looks far more like Envestnet or Orion — a technology platform that facilitates advisers implementing a wide range of third-party outsourced or adviser-managed portfolios — and positions itself as a technology solution more so than a traditional TAMP, even as the firm primarily charges basis points like an investment manager. That helps to highlight just how murky the dividing lines between TAMPs, SMA/model platforms and pure technology solutions have become.

Ultimately, though, the real challenge for Geowealth will arguably not be one of technology, but of distribution. Most of the household names in the TAMP space have become so through large enterprise relationships, especially large independent broker-dealers, because the provider can complete a selling agreement and have access to hundreds or thousands of advisers and their assets. Yet Geowealth focuses on RIAs — which do have a simpler and faster sales cycle than a complex broker-dealer arrangement, and often better economics for the TAMP provider by cutting out the broker-dealer middleman — but therefore has to figure out how to reach the much more fragmented and hard to reach RIA firms.

As in the end, just like so much other technology in the world of AdviserTech, it’s not an “if you build it, they will come” path to success. The biggest driver of outcomes isn’t necessarily who can build the best tech, but who can figure out the most efficient way to distribute it and get it into the hands of advisers themselves. That’s a mountain that Geowealth still has a long way to climb.

Over the past decade, the dividing line between technology and investment management has blurred more and more, as exemplified by the rise of the robo-adviser as a tech-enabled asset manager. Ironically, though, robo-advisers positioned themselves as a technology platform and not an asset manager, even though they priced their services in basis points on assets, whereas in the financial services industry, the dream of most technology firms is to be able to price in basis points like an asset manager (and not in flat per-user software fees).

Accordingly, one of the biggest trends among technology firms in recent years has been to position themselves closer and closer to the asset management industry in an attempt to participate in the basis-point pricing of asset managers — from tech companies that are monetizing with/through/as TAMPs (e.g., Geowealth and Envestnet), to tech companies that have tried to roll out model marketplaces to participate in and profit from asset management distribution (e.g., Riskalyze and Oranj), or in some cases tech companies that just outright acquire and try to convert some of their users into TAMP advisers (e.g., Orion/Brinker).

In this context, it is notable that in October, Pershing announced ITS latest platform, Pershing X, which it describes as an “all-in-one” set of technology capabilities (as an alternative to the traditional patchwork of third-party vendors), built on top of the Pershing custody/clearing platform and including access to BNY Mellon’s Investment Management platform.

In part, the Pershing X announcement is notable for its pledge to once again pursue the infamous Holy Grail of the all-in-one, does-everything-you-need, fully integrated platform. In theory that’s very appealing, for all the ongoing woes that financial advisers have in trying to patch together their independent best-in-class technology providers. Except at the same time, the reality is that both Schwab and Fidelity, along with numerous other broker-dealers and AdviserTech providers, have tried to build all-in-one platforms, none of which managed to actually be competitive in patching together third-party solutions (at least not for any sustaining period of time). And despite noble intentions to finally solve the problem, it’s hard to be anything but skeptical about why “this time is different” with Pershing X?

In fact, given the ongoing woes of attempts to build all-in-one solutions, the Pershing X announcement is notable for the underlying adversarial tone it takes toward third-party providers. Few would deny that integrations could and should be a lot better. However, third-party providers are well adopted by advisory firms for a reason. Firms like Orion, Black Diamond, Tamarac, MoneyGuidePro, eMoney and Riskalyze collectively invest many millions of dollars a year in R&D to solve the specific problems that they encounter with their advisers day in and day out. And still, even with all of that collective investment, an incredibly small percentage of firms use any of those providers as all-in-one platforms. There are just too many boxes to check for any one firm to do all of them incredibly well; thus the need for a technology stack.

In the end, it’s not clear if Pershing is really trying to solve a technology problem, per se, or instead is simply trying to convert its underlying custodial business (and its associated tech) from a traditional transaction-based business model into a basis-points pricing structure instead by utilizing the technology to drive assets to its asset management division through some combination of TAMP- and/or model-marketplace-style offering that sits behind Pershing X. Stated more simply: It appears that Pershing X is less a technology solution for the sake of solving an all-in-one technology problem for advisers, and more a strategy of technology-as-a-distribution-channel-for-asset-management-bps instead.

Of course, the reality is that the asset management business can be very profitable, with strong flows and a significant asset base for scale, which ironically means that the level of development and reinvestment possible if Pershing X really can generate asset flows may actually give it the capital to build the technology that none else have managed to build as a technology solution alone. Still, though, with the challenging track record of all-in-one solutions to date from any provider, the question remains of whether Pershing will really be able to build something that lets it earn asset management basis points for (snazzier) custodial technology?

Fulfilling compliance is a necessity and an obligation in a highly regulated industry like financial services. Yet despite the ubiquity of its need, in practice there is remarkably little invested into the development of regtech. While every firm needs to fulfill its compliance obligations — and could benefit from technology to do so — compliance tends to be an area where most advisory firms don’t invest for efficiency. Instead, most manage costs by minimizing their spending to the lowest amount necessary to check the boxes that must be checked (and nothing more).

Still, though, because compliance involves ongoing repetitive tasks — which tends to make them highly conducive to technology to facilitate or automate — there is often a hunger for regtech to support compliance functions within advisory firms. The gap is just the budget to fund it.

In this context, it’s notable that that in October, Orion announced the acquisition of BasisCode Compliance, which had built a suite of regtech tools to facilitate enterprise compliance functions like scanning employee trading activity for front-running or insider trading risks, verifying staff certifications of trading activity, reporting of gifting and entertainment, automating employee conflict-of-interest compliance and facilitating compliance audit reviews.

Strategically, the deal makes sense for Orion. With the acquisition of BasisCode, Orion brings a more robust set of compliance capabilities it can package into its core platform as part of a sale to larger-scale adviser enterprises (e.g., large RIAs and midsize-to-large broker-dealers), similar to its other recent acquisitions to bolster its core offering, including financial planning (Advizr) and risk analytics (Hidden Levers). Though in practice, Orion may get even more traction with its BasisCode offering, as while financial planning and risk analytics are already crowded categories — most enterprises already have a solution, and advisers tend not to switch what they’re already using — because regtech is systematically underinvested, it’s even more likely that Orion will be able to open doors with BasisCode into enterprises that may not need another planning software tool but really need more (bundled) compliance tech.

Ultimately, perhaps the bigger risk for Orion in its acquisition of BasisCode is simply that it’s yet another acquisition by Orion in relatively quick succession, raising the question of whether Orion can fully digest the integration of BasisCode on top of already integrating Brinker, Advizr and HiddenLevers. Is it too much to digest at once, and will the adviser/client experience suffer?

In the long run, though, the acquisition of BasisCode, on top of Orion’s other recent transactions, is increasingly positioning the company out of its historical “portfolio management and performance reporting” category alongside the likes of Black Diamond, Tamarac and Addepar, and into the all-in-one platform category against Envestnet, with a combination of portfolio management, financial planning, risk analytics and compliance, all bundled around a platform TAMP offering via FTJ Fundchoice and Brinker. With Envestnet so deeply entrenched into large RIAs and midsize-to-large broker-dealers already, BasisCode gives Orion a unique new angle to try to get its foot in the door?

While CRM systems are a staple of service businesses across a wide range of industries that need to keep track of their customers or clients and their ongoing service interactions, the industry-specific compliance demands and cross-platform integrations necessary to implement CRM in an advisory firm means that in practice, almost all adviser CRM systems are adviser-specific systems — from Redtail to Wealthbox, Advzyon to Junxure — and the few more generic solutions (e.g., Salesforce and Microsoft Dynamics) typically only complete by partnering with overlay providers who create adviser-specific templates (e.g., Skience, XLR8 and PractiFi) that add the typical information fields that advisers use.

Yet in recent years, CRM systems have begun a shift from being the contact-information-and-working-notes storage area for client relationships to serving more as a workflow engine that tracks and manages the activities within the advisory firm, especially the tasks that span across multiple systems (where data itself may need to flow from one system to another). That’s opened the door for increasingly sophisticated overlay systems — particularly on top of Salesforce, which has a more robust engine for integrations and workflows than most industry-specific systems — to become the enhanced engine for making the most of out-of-the-box CRM systems.

So it’s notable that in November, Skience — one of the more popular Overlay providers for Salesforce — announced a new integration with Redtail, which will begin to flow Redtail client data into Skience’s client onboarding workflow engine.

At the most basic level, the significance of this news is that Skience itself is broadening beyond just being a Salesforce overlay, taking the tools that it’s built (from digital onboarding for clients, to tools that facilitate the repapering process for adviser transitions as they’re recruited from one firm to another), and rolling them out as support tools to enhance multiple CRM systems.

More broadly, though, the real impact of Skience’s announcement is that even as advisers begin to shift from having their broker-dealer or RIA custodian as the hub of their systems to using CRM as the hub instead, Skience is creating an infrastructure that positions it to be an operating system for wealth management firms regardless of the CRM system.

In other words, an advisory firm may want to use Redtail as their CRM, or prefer the scalability and configurability of Salesforce, but no matter how a firm wants to handle the selection of the CRM interface itself, Skience is building the core operating elements that feed into the CRM system — from data aggregation and warehousing to (multi-)account opening and repapering, and compliance functions from trade surveillance and document storage — that add value to the implementation of any CRM system deployed in an advisory firm. (Which means it’s likely only a matter of time before Skience adds Wealthbox, Microsoft Dynamics and other CRMs as well.)

Leveraging Skience to overlay adviser CRM systems also makes it easier for advisers to eventually switch CRM systems in the future. Not that advisers need to frequently make changes to CRM systems — in fact, CRM turnover tends to be fairly low among financial advisers — but there is a typical progression that the CRM systems used by small-to-midsize firms (Redtail and Wealthbox and Advyzon) are different than those used by midsize firms (Redtail and Junxure), which are different than the most common systems among large firms (Salesforce and Dynamics). It’s a spectrum that becomes easier to navigate when key functions integrate to adviser CRM systems but aren’t dependent on any one in particular. (Albeit at an extra cost of paying for Skience on top of the underlying CRM system.)

Beyond CRM independence, though, perhaps the biggest potential impact of the kind of solution that Skience is building is that it accelerates the independence of advisers from their broker-dealer or custodian platforms, which historically have been the dominant operating system for advisory firms. In part, the shift appears to be driven by the fact that the largest platforms have become so large they’ve struggled to keep up with the pace of innovation for new tools and developments (as evidenced by how badly most broker-dealers and custodians lagged in digital onboarding compared to robo-advisers over the past decade). But it’s also a sign of the shift away from investment- and asset-centric business models into more advice-centric businesses that by definition are less dependent on their investment platforms to execute their businesses.

Technology conversions are no fun for most advisory firms, no matter the type of product, because most advisers set out to serve clients, not solve technology problems. But the more that advisers shift toward independence, the more important it becomes to control their own foundation. That augurs well for CRM to be positioned as the hub of the future — and positions Skience well to be the hub that powers CRMs?

One of the most intractable challenges of the U.S. workplace-provided benefits systems is that it’s difficult to get small businesses to adopt such employee benefits in the first place. In some cases, the challenge is the cost of the plans — either the cost to set up and administer, or more commonly the cost of employer contributions into the benefits (from covering a portion of health insurance to the paid match/contribution for a 401(k) plan). More often, though, the challenge is simply that small-business owners are busy, with limited time and bandwidth to figure out what to offer in the first place.

The emerging alternative in recent years has been the advent of state-sponsored, automatic-enrollment IRAs (for employees who don’t have 401(k) plans through work), and the rise of other state-operated programs like 529 college savings plans (and their 529 ABLE account brethren for disabled beneficiaries). But even in the case of auto-IRAs and 529 plans, someone still has to administer the plans, facilitate enrollment and try to encourage employees/citizens to actually participate and contribute to the programs. This is in an environment where there’s immense pressure on traditional record keepers for employee benefits, which often have outdated technology and are facing a growing margin squeeze as ERISA fiduciary regulation steadily squeezes out historically lucrative proprietary products and shelf-space agreements.

Against this backdrop, Vestwell has emerged as a next-generation 401(k) record keeper that’s been making steady headway in competing against traditional record keepers by working directly with financial advisers who want a more modern robo-style digital experience for 401(k) onboarding and implementation.

In November, Vestwell announced a major deal to acquire Sumday from BNY Mellon. Sumday handles the back-end administration for a number of states’ 529 college savings and ABLE accounts, along with a Secure Choice IRA that can fulfill the auto-IRA obligation for small businesses in states that mandate the employer implement an IRA if a 401(k) plan is not offered.

Beyond the straightforward opportunity to gain additional economies of scale by administering more assets across more different programs through its systems, though, the significance of the Sumday acquisition for Vestwell is a unique form of asset consolidation that’s happening across and through AdviserTech platforms.

The idea is that an AdviserTech provider has an insight or design process that creates a tool or offering that leads to a better adviser experience (or candidly is sometimes just a better overall mousetrap). Once its technology has reliably been established and gains traction, the company begins to seek out acquisition targets purely based on the amount of assets they would be bringing over to add mass to the system. Envestnet did this with the acquisitions of Placemark and FolioDynamix, and Orion has done it with its FTJ Fundchoice and Brinker Capital. It seems as if this is a similar play by Vestwell (with the added benefit of some additional 529 expertise and technology).

That means Vestwell’s Sumday acquisition is likely the first of more to come in a kind of record keeper/administration roll-up opportunity. That leaves Vestwell positioned well, as it will have its pick of the litter when it comes to this strategy as more and more companies seem to be flooding out of the retirement business, given the headwinds of increased regulation, limitations on selling proprietary funds and low overall profitability. (While Vestwell has built its platform more recently, leveraging more modern technology infrastructure to scale in a more cost-effective way.)

From the adviser perspective, more deals and programs for Vestwell means more offerings that advisers may be able to facilitate through Vestwell for their small-business clients, especially as the lines blur between employer-provided benefits and state-sponsored programs that happen to be implemented through employer payroll systems (which makes 401(k) plans and state auto-IRAs first cousins to one another). Envision a system where advisers get an ever-growing list of programs that their small-business-owner clients can implement for their business/employees, all via a single central platform, and advisers help to bridge the adoption gap by being the advice provider on the spot who makes a recommendation and helps with follow-through implementation to create value for their business owner clients?

For most of its history, the world of adviser technology has largely been a cottage industry of homegrown solutions. The creation story is usually exactly the same: Adviser struggles with a challenge in their businesses for which they can’t find a solution, eventually decides to build their own technology to solve the problem, begins to sell the software to other advisers who also face the same struggle, and ends up with a software company on the side. Thus was the path of many of the most popular adviser software solutions of years past and present, including Junxure CRM, Redtail CRM, ProTracker CRM, Orion AdviserServices, Tamarac, Oranj, iRebal, TradeWarrior, tRx, Rebalance Express by RedBlack, Capitect, Tolerisk, RiskPro, eMoney Adviser, Advizr, Hidden Levers and AdvicePay, among others.

Yet while in practice the homegrown-tech approach has yielded many of today’s most popular AdviserTech solutions — driven by the intimate understanding of the Job To Be Done when technology is built “by advisers, for advisers” — the reality is that most financial advisers have little to no experience actually building technology and what it takes. That means for every AdviserTech homegrown solution that made it, there are likely three, five or 10 other solutions that advisers tried to build, but never figured out how to effectively navigate the dynamics of hiring and managing product designers, developers, support, and the sales-and-marketing that it takes to actually build a successful technology business.

In an attempt to help fill this void, back in 2018, the Tifin (Technology in Finance) Group launched, with a vision of operating as a part-incubator-part-dev-shop with small adviser technology solutions to help them build successfully. After two years of incubation, and a successful sale of one of its portfolio companies, 55ip, to JP Morgan, Tifin pivoted in late 2020 to a more direct operating model of trying to not just incubate but grow and scale the technology companies together under its umbrella.

In turn, Tifin’s new focus on growing and scaling AdviserTech solutions has led to a rapid sequence of capital rounds — a $22 million Series A in December 2020, another $22.3 million Series B in April, and now a $47 million Series C in October — in an effort both to expand the technology and scale the distribution of its portfolio companies, acquire new AdviserTech solutions to broaden its portfolio (most recently including Totum Risk and MyFinancialAnswers), and begin to develop the consumer side of its marketplace by acquiring consumer media companies with existing audiences who might someday be paired via Tifin with advisers as a lead generation service.

At its core, then, Tifin Group is positioned in two of the hottest areas of AdviserTech — the red-hot category of adviser lead generation, where advisers have demonstrated a willingness to pay as much as 15% to 25% of lifetime revenue worth thousands (or tens of thousands) for high-quality leads that turn into clients, and creating (truly) integrated technology that allows advisers to operate more efficiently without needing to live with a patchwork of existing best-in-class solutions that don’t always talk well to one another.

The caveat, though, is that while adviser lead generation has very lucrative economics on paper (with extraordinary lifetime client values just for providing leads that close), there’s a reason why client leads are so valuable: Lead generation is hyper-competitive, with very high multi-thousand-dollar client acquisition costs per client, and it’s very, very difficult (and costly) to scale a large volume of client leads (as robo-advisers, among others, have learned the hard way). At the same time, while advisers have long longed for the Holy Grail of an all-in-one technology solution that is competitive with best-in-class one-offs but exists in fully integrated form, in practice all providers that have attempted such a quest have failed to maintain their competitiveness as individual technology categories tend to iterate far faster than an all-in-one can maintain.

In other words, the question for Tifin Group is whether an infusion of capital, with centralized development and resources, can actually incubate and scale a large number of AdviserTech solutions into a roll-up where the whole really is worth more than the sum of the parts — or if Tifin instead will struggle to find ways to bring it all together in a coherent way and remain trapped in a world of disparate parts that don’t really fit together into a bigger picture of success.

If it works, Tifin will likely become a model for others who similarly seek out nascent homegrown AdviserTech solutions, and offer to acquire and bring them under the fold to distribute and scale as a form of AdviserTech innovation cycle. That could ultimately accelerate the pace of industry innovation when it becomes clearer that AdviserTech entrepreneurs have pathways to grow and scale more quickly once they initially validate their offering and demonstrate a real product-market fit. Yet in the end, success as an AdviserTech roll-up still depends on the success of its individual components each adding enough value to attract advisers as users, and at this point, the jury is still out on whether Tifin Group has even managed to bet on the right companies in the first place?

Notwithstanding the tremendous growth over the past 20 years with the industry's shift from commission-based to advisory accounts, the assets under management model is still fundamentally limited: It only works with clients who have assets to manage in the first place. That means that not only is the AUM model limited to just a subset of clients who want to delegate their portfolio to a third-party adviser to manage, it also necessitates having assets that can be delegated in the first place. That’s especially problematic when it comes to employer retirement plans, that typically don’t connect to traditional brokerage accounts and portfolio management/trading systems, and in practice aren’t accessible or feasible for most advisers to manage.

Historically, this requirement has led financial advisers to take a special focus on prospective retirees — not only because they tend to have accumulated substantial potential assets to manage by the time they can afford to retire, but also because the retirement transition itself often unlocks a significant pool of available assets: the 401(k) balances and the lump-sum equivalent of a defined-benefit plan, which suddenly become available to roll over (to the adviser’s management) when the new client retires (and separates from service).

In recent years, though, a new trend has begun to emerge: the assets under advisement model as an alternative to the AUM model, where advisers advise on assets that are held outside of their traditional account structures, and charge an ongoing advice fee for monitoring, portfolio reviews, and periodic trading/rebalancing recommendations. That allows the adviser to expand their value proposition beyond just the client’s currently available to manage investment accounts, creating growth by expanding the relationship with existing clients.

The caveat, though, is that because advisers typically manage the portfolios under their (discretionary) control, but only advise on held-away accounts, there is often a limitation on the depth of value provided, and therefore on the fees that can be charged. That makes it especially appealing to find a way to actually manage held-away accounts, being able to do trades in those accounts, and therefore making it feasible to justify a (higher) bona fide investment management(AUM) fee.

A few years ago, that led FeeX to launch a service specifically to facilitate the management of held-away 401(k) accounts, where the company has created its own version of an order management system for third-party 401(k) plans by getting permission from clients to be able to access their accounts directly to enact trades at the adviser’s direction (but without granting the client’s password to the adviser for direct login access, to avoid triggering custody for the adviser). It effectively turned the AUA model for held-away 401(k) plans into a more traditional AUM model.

Now FeeX is rolling out a growing number of integrations to existing portfolio management systems for independent advisers, including Orion earlier this year, and more recently a new integration with Advzyon. That makes it possible for advisers to manage (and facilitate the billing process for) clients’ 401(k) plans directly through their existing portfolio management and reporting systems, in a form of unified trading of on-platform and held-away accounts.

Notably, the expansion of the AUM model to an AUA approach for held-away assets comes at a time when large national providers are increasingly trying to deploy financial advisers directly into the 401(k) channel as well, with deals ranging from Financial Engines acquiring Edelman Financial, Empower acquiring Personal Capital and large record keepers like Fidelity increasingly cross-selling their own internal advisory services to their existing plan participants. That means that just as 401(k) plan providers are trying to retain 401(k) assets by establishing advice relationships with their plan participants before they can be introduced to an independent adviser to roll over, independent advisers are moving into the business of managing (still held-away) 401(k) assets to expand those relationships in the “pre-rollover” stage as well.

The good news of this shift is that in the long term, it increasingly positions advice and advice relationships as the central value propositions that attract and retain clients (regardless of their current stage of life or where their assets are held). The bad news, though, is that it will increasingly challenge financial advisers focused on pre-retirees transitioning into retirement, who in the future, appear less and less likely to have any money in motion at retirement because they are more and more likely to already have a holistic adviser relationship long before they get to the retirement transition?

Driven by exchange-traded funds’ popularity as the new low-cost building block of client portfolios, financial advisers in recent years have increasingly begun to construct portfolios using ETFs instead of mutual funds, helping to drive U.S.-based ETF assets to nearly $7 trillion of total AUM this year. However, the reality is that the bulk of investment assets are still in mutual funds, which total nearly $24 trillion of AUM, and many advisers still hold wide swaths of client portfolios in mutual funds. That can create unique challenges in years like 2021, with the S&P 500 up more than 20% this year, and up more than 100% from the pandemic low less than two years ago. With growth comes capital gains, and with mutual fund growth comes the potential for end-of-year capital gains distributions. This year, more than 750 mutual funds are projected to distribute at least 10% of their NAV, with more than 100 distributing 20%-plus of their value, and more than two dozen projected to distribute 30%-plus of their NAV in December!

From the adviser perspective, late-year capital gains distributions create a number of tax planning challenges, including a potentially material impact on total income for the year (which can change the optimal amount of dollars to convert for Roth conversions, or trigger a Medicare IRMAA threshold), the risk that a new client buys into a mutual fund right before it makes a capital gains distribution for prior gains (sticking a new shareholder with an immediate tax liability for gains they didn’t even participate in!) and at best an awkward conversation when clients realize that all the growth they’ve been earning has now come home to roost for tax purposes.

As a result, it’s important to get a handle in advance on what capital gains distributions will be before they actually occur (often in just the last two weeks of December, when it’s too late to do much planning). Except in practice, many mutual funds don’t even know what their gains distributions will be until relatively late in the year, as it depends on what trading they actually do (and what gains are turned over) right up through December. And each mutual fund family (and sometimes different funds within a fund family) has its own timing about when they do the calculations on expected gains and share that information with shareholders and their advisers.

In recent years, that’s led to a rise in third-party solutions that help advisers by aggregating all the mutual fund estimates from a wide range of mutual fund providers (and also capturing the small subset of ETFs that can and do occasionally make capital gains distributions as well), including both BlackRock’s Tax Evaluator, and CapGainsValet.

At their core, both services are similar in giving advisers the ability to look up capital gains distribution estimates for a wide range of fund families all in one place, with BlackRock allowing advisers to upload client portfolios and get the estimated size and date of anticipated distributions for each holding, while CapGainsValet simply provides a giant list of fund families and their tickers to look up (including a free search for the roughly 20 largest fund families, including American Funds, Pimco, Vanguard, Franklin Templeton, DFA, etc., that make up the overwhelming majority of fund assets, and a pro search for a small $45 fee that opens up a list of more than 250 fund families).

In practice, the BlackRock tool will probably be more appealing for advisers who have client portfolios with a wide range of holdings, while CapGainsValet is a more straightforward solution for those who have standardized models and just want quick and easy access to get the estimates for a few specific funds/holdings that all of their clients own. (Notably, though, CapGainsValet also has a Delivery service for a small additional fee, where advisers can provide a longer list of funds/tickers, and receive a weekly updated list of distribution estimates that becomes fully populated over time as all the fund companies eventually release their distribution estimates.)

In the long run, arguably these types of capital gains estimates should be captured directly by portfolio performance reporting and trading solutions, which would gather the data together and display it to advisers directly in their performance reports for clients and their trading tools (to avoid the risk of accidentally buying a new fund right before it makes a distribution). But until the capabilities are integrated more directly, solutions like BlackRock’s Tax Evaluator and CapGainsValet do at least make it easier for advisers to gather (and monitor) the information they need for end-of-year tax planning and investment decisions.

From its earliest days, financial planning was a form of consultative selling, where advisers would explore a wide range of potential financial issues and needs that a prospect might face, and then deliver a comprehensive financial plan to identify their gaps, which could subsequently be filled with the sale of the financial adviser’s products. Relative to the alternative at the time — having a single product that would be pitched to every prospect until someone said yes — financial planning was a resounding success, uncovering a wider range of business development opportunities (than just what a single product could fill), while at the same time providing genuinely better solutions and outcomes to clients (who actually got more of what they needed, and not just the one thing that the financial salesperson had to sell).

The challenge, though, is that training a new financial adviser on the features, benefits, and sales scripts of a single product was relatively straightforward to teach, while doing more comprehensive financial planning had a much more challenging learning curve, requiring more education, more training, and more practice and experience with clients. Such that in practice, financial planning was something financial salespeople were only allowed to graduate up to after they achieved many years of financial success going the single-product sales route.

In more recent years, financial products have become increasingly accessible to consumers (directly) thanks to the internet, and financial advisers are being driven even further in the direction of providing financial planning as their primary value proposition — with the caveat that it hasn’t gotten any easier to progress through the training and development curve of learning to do financial planning. If anything, advisers have increasingly tried to become more comprehensive in the depth and breadth of their financial plans — to show differentiated value from all the other financial advisers also offering financial plans — making it even more challenging for any one financial planner to learn everything there is to know. In other words, even well-trained financial planners can still struggle to think of all the financial possibilities and planning scenarios that might exist with any one prospect.

In this context, it’s notable that in November, FP Alpha launched a new Prospect Accelerator, specifically designed to take in information from prospects and help financial advisers identify potential planning opportunities that may be on the table.

In essence, FP Alpha can function as a form of internal checklist — taking in a wide range of prospect data through a questionnaire advisers embed on their website, checking it against a long list of potential planning ideas, and surfacing back to the financial adviser (and prospect) the areas where the adviser may be able to add value (or at least should dig deeper in a follow-up conversation with the prospect).

In addition, FP Alpha’s Prospect Accelerator will evaluate the prospect’s overall financial health, and provide a financial wellness score, which serves as the basis to create a financial planning proposal that can demonstrate how the prospect, in working with the adviser to implement recommendations, will be able to increase their financial wellness score (and allow the adviser to show, over time, how their client’s score has increased).

In the future, anticipate that FP Alpha will be able not just to gather information via prospect questionnaires, but have prospects upload primary documents — e.g., tax returns and estate planning documents — for the software to scan and identify further planning opportunities (building on FP Alpha’s existing core capabilities as a financial advice support tool after prospects have already become clients).

Ultimately, it’s not clear whether FP Alpha will realistically be able to find planning opportunities that any skilled financial adviser couldn’t identify on their own (though at the point it can scan dozens of pages of primary documents in seconds, FP Alpha really may be far more time-efficient than an adviser reading the client’s documents themselves). Instead, the appeal of a tool like Prospect Accelerator is in part as a de facto planning checklist (instantly reviewing far more potential planning ideas and scenarios than any one adviser might be able to recall offhand), in part a consistency tool (e.g., a multi-adviser firm might be concerned that not all advisers will spot the same planning opportunities, but FP Alpha will do so the exact same way every time), and in part simply a prospect engagement tool to help advisers demonstrate value (by surfacing a financial wellness score for prospects, which inevitably won’t be perfect, and show an opportunity for the financial adviser to be hired to improve the prospect’s financial scenario).

For most of its history, estate planning has been one of the foundational domains of financial planning. In part, this is because having one’s financial house in order — including clarity about what happens to their assets after death or in the event of incapacitation — is simply “good planning” in the first place. But estate planning has also long been a part of financial planning because, in the early decades of financial planning, the federal estate tax exemption was so low (at just $60,000 up to 1976, and ranging from $120,000 to $600,000 from 1977 to 1997) that having a prudent amount of life insurance to protect a family would cause an estate tax problem (which mean advisers needed to do estate planning with vehicles like irrevocable life insurance trusts to mitigate that estate tax exposure).

But that dynamic began to change in 2001, when President Bush signed into law the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act, which immediately increased the estate tax exemption from $675,000 at the time up to $1 million, and set it on a path to rise as high as $3.5 million by the end of that decade, which with subsequent adjustments has risen today to $11.7 million (per person, doubled for a married couple), far outpacing the general level of inflation. The end result is that exposure to the federal estate tax has plummeted, from more than 50,000 taxable estates in 2001 to recent IRS data showing just 1,275 families paying a federal estate tax in 2020 (a decrease in federal estate tax exposure of nearly 98%).

As exposure to the federal estate tax has declined, so too has the estate planning focus in financial planning, with the weighting on estate planning in the CFP Board Principal Knowledge Topics decreasing to just 10% in the latest job task analysis. As estate planning itself increasingly shifts from estate tax planning, to the nontax planning issues surrounding the estate itself, including who will inherit assets, and under what terms, along with provisions for who will be responsible for making financial and other decisions on behalf of heirs (i.e., guardians and trustees of assets held in trust) or the individual themselves (i.e., in the event of disability or incapacitation).

Accordingly, in recent years, a number of new providers have emerged, aiming to support financial advisers in their modern estate planning, which is less about estate tax planning strategies, and more about simply ensuring that clients have the estate planning documents they need in the first place. That led to a new category of estate planning service providers, such as Helios Estate Planning, Trust & Will and Vanilla, in addition to longer-standing online legal documents solutions like LegalZoom.

But last month, Helios abruptly stated that it was shutting down, with an immediate cessation of new clients as of the Nov. 15 announcement, a short wind down of existing estate planning clients over the subsequent week (which was feasible as Helios tended to focus on simpler clients whose documents could be prepared relatively quickly), and a refund of any unused credits that advisers already had paid into the system for future clients who hadn’t actually completed their documents yet. Leaving a lot of advisers wondering, “What just happened!?”

In the short term, the wind down of Helios will likely be a boon for its competitors, as the competitive landscape itself shrinks (with Helios no longer a player), and as the advisers who were already using Helios look for alternatives — most likely Trust & Will for their smaller clients and Vanilla for their more affluent, ultra-HNW clients (where Vanilla really excels).

From the broader perspective, though, the demise of Helios raises the question of whether estate planning itself is becoming so de-emphasized in modern financial planning that it’s simply not a viable service at all to offer to financial advisers (at least, outside of the ultra-HNW domain where there is still a high-value federal estate tax problem to plan around?).

In the end, though, it appears that Helios may have struggled with its particular level of estate planning being offered, and not necessarily that advisers don’t want to engage around estate planning issues at all. In practice, Helios was positioned as a firm that wasn’t just a pure technology-driven document generator, but one staffed by human attorneys drafting and reviewing documents. But because Helios was focused on simpler estate planning documents for less affluent clients, it was often forced to compete at the lower end of the pricing scale, where more purely tech-driven solutions like LegalZoom and Trust & Will operated. The cost of humans at the price of automated technology simply may not have been a viable business model, or at least not viable to scale without capital (as Helios was not known to have taken any outside investors, and instead was being funded as a bootstrapped extension of its separate but related Helios Asset Management business).

Still, Helios’ woes do help emphasize that when it comes to estate planning, two branches are emerging: 1) those clients who do still have bona fide federal (or in some cases, state) estate tax problems and have significant dollars at stake, significant complexity and a willingness to pay substantial fees for estate planning help (where advisers and attorneys can be highly engaged, and rewarded well for their time spent); and 2) everyone else, who don’t have an estate tax problem and just need to get their estate planning documents in place, who are significantly more fee-sensitive and where human advisers and attorneys will struggle to be profitable, where advisers can simply refer out to technology-driven document preparation services for clients to get what they need?

That means there’s arguably room for both HNW solutions like Vanilla to succeed (competing with expertise at the top end of the market), along with simpler document-generation alternatives like Trust & Will for the average client (competing on cost and convenience at the low end of the market). Helios unfortunately may have just gotten caught in the messy middle?

When the early robo-advisers like Betterment, Wealthfront and FutureAdviser first hit the scene nearly a decade ago, they staked their value proposition on the idea that all financial advisers did was gather basic data about client ages, time horizons and risk tolerance to construct a diversified asset-allocated portfolio, and that technology could gather the same information to construct the same portfolio for a small fraction of the cost, aiming to ratchet the traditional 1% AUM fee down to just 0.25% instead.

As robo-advisers garnered their initial assets, expectations grew — rather dramatically. In the span of just five years, from 2012 to 2017, Betterment raised $272 million in capital over five rounds of funding as it grew from $50 million of AUM to $10 billion. Wealthfront similarly raised $194 million from 2013 to 2018 and grew from $250 million of AUM to nearly $10 billion of AUM as well. Wealthfront was rumored to have received a $700 million valuation in late 2014 and Betterment similarly received a $730 million valuation in 2016. An A.T. Kearney study predicted that pure-technology robo-advisers would begin to rapidly displace human financial advisers, projecting $2 trillion of robo-adviser AUM by 2020.

Yet today, Betterment manages just $28 billion of AUM (though at a quarter of the typical adviser fee, from a revenue perspective they are more akin to a $7 billion advisory firm), and Wealthfront is at $24 billion of AUM (akin to a $6 billion traditional advisory firm). Both are very sizable advisory firms, but at a combined roughly $50 billion of AUM, they’ve captured barely one-fortieth of their predicted assets.

Accordingly, it was notable that in September, Betterment raised a fresh round of capital at a valuation of just $1.3 billion, while Wealthfront is reportedly trying but struggling to find a buyer at a list price of $1.5 billion. Both transactions place the robo-advisers in the vaunted territory of unicorns — tech firms that have garnered a valuation of greater than $1 billion — but also represent an astonishing stumble from the robos’ take-over-the-world implied valuations during their early years.

While it is notable that both firms have managed to garner valuations of nearly double where they were five to seven years ago, markets themselves are up nearly 130% over that time period (and an 80/20 portfolio of a typically younger and more aggressive robo-adviser client would be up more than 100% over the years since their last capital rounds). That means that while robo-adviser AUM is up two to three times from where it was, robo-adviser valuations today haven’t even kept pace with the passive growth of the markets!

Ultimately, the fact that growth in robo-adviser valuations hasn’t even kept up with market growth — even as the two leading platforms have each added an average of several billion of new AUM per year — helps highlight just how much growth was already priced into the early valuations (though commentary at the time had suggested that their growth expectations seemed unrealistic), and signals just how difficult it is to rapidly scale an advisory business given the incredibly high client acquisition costs. Financial services — a low-trust industry trying to command high-stakes decisions about one’s life savings — is quite unforgiving with an ‘if you build it, they will come’ approach to growth.

In the end, the leading robo-advisers that survived are still on track to have built substantively valuable ($1 billion-plus valuation) businesses, and while robo-advisers fundamentally misunderstood what financial advisers are paid for — which is driven much more by acquisition of clients and the ongoing advice relationship to establish trust in a low-trust industry — they have helped to drive a massive retooling of the back-office of advisory firms (e.g., the rise of esignature and digital onboarding) that is driving increases in staff productivity.

So for all those who were skeptics of the eye-popping valuations of robo-advisers during the height of the robo craze, the recent rounds of capital and prospective sales of the early robo-advisers simultaneously highlight that expectations of robo-advisers were substantively overstated, but that robo-advisers, and the technology they represent, are here to stay. Even if the benefits of that technology didn’t exactly play out in the ways that the robo-adviser founders had hoped.

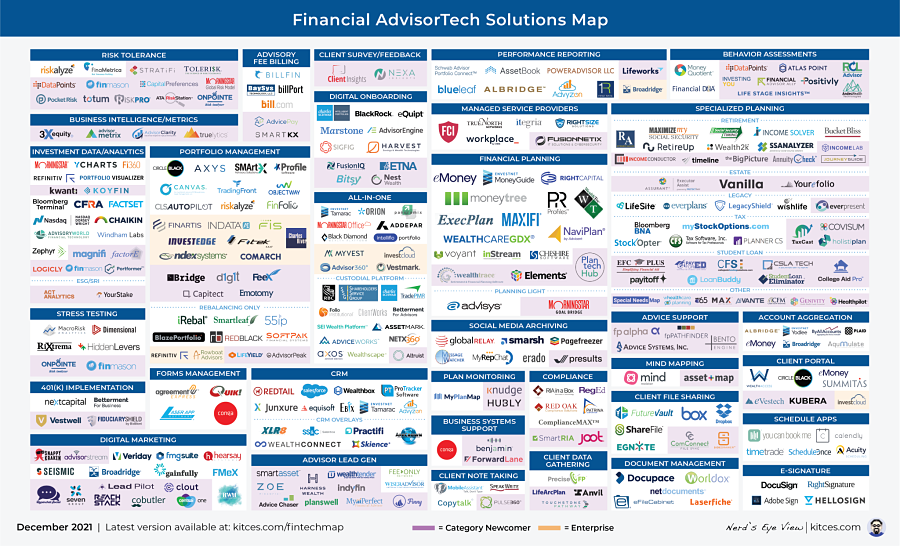

In the meantime, we’ve updated the latest version of our Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map with several new companies, including highlights of the “Category Newcomers” in each area to highlight new FinTech innovation!

So what do you think? Can Geowealth gain market share in the hyper-competitive TAMP environment? Will TIFIN Group be able to weave together its tech components into a cohesive whole that advisers will use? Can Pershing X finally succeed in creating an all-in-one solution (that advisers will pay basis points for)? Will more advisers continue to adopt structured notes and annuities to manage growing concerns of reduced equity returns in the years to come?

Disclosure: Michael Kitces is a co-founder of AdvicePay, and Kyle Van Pelt is the executive vice president of sales at Skience, both of which were mentioned in this column.

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter at @MichaelKitces.

You can connect with Kyle Van Pelt via LinkedIn or follow him on Twitter at @KyleVanPelt.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound