The July edition of the latest in financial #AdviserTech kicks off with the big news that Charles Schwab agreed to pay a whopping $187 million to settle charges from the Securities and Exchange Commission that it misled investors by advertising that its Schwab Intelligent Portfolios robo-adviser was “free.” In reality, Schwab not only was profiting on investor cash that was being swept to its affiliated Schwab Bank, but set its cash allocation targets in client portfolios at above-typical levels specifically to ensure it achieved its desired level of business revenue from its robo-offering. This was achieved by reducing long-term client returns by an amount equivalent to the advisory fee it said it wasn’t charging but indirectly generated anyway.

The significance of the Schwab settlement is not only its sheer magnitude — at $187 million, it is likely enough to wipe out virtually all profits that Schwab ever earned on its robo-adviser in seven years. This is equivalent to the profits on $375 billion of assets under management assuming a 25-basis-points fee and a 20% profit margin, while Schwab’s robo-adviser itself reportedly had just $65 billion of AUM last month. This raises questions about whether Schwab’s other lines of business, including its RIA custodial offering, may also face regulatory scrutiny, given that Schwab’s “pledge” not to charge RIA custody fees while profiting from the cash sweep to Schwab Bank is remarkably similar to the marketing tactic it just settled with the SEC for its “no-fee” robo-adviser.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting adviser technology announcements, including:

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in adviser technology, including:

In the meantime, we’ve also made several updates to the beta version of our new Kitces AdviserTech Directory, to make it even easier for financial advisers to look through the available adviser technology options to choose what’s right for them.

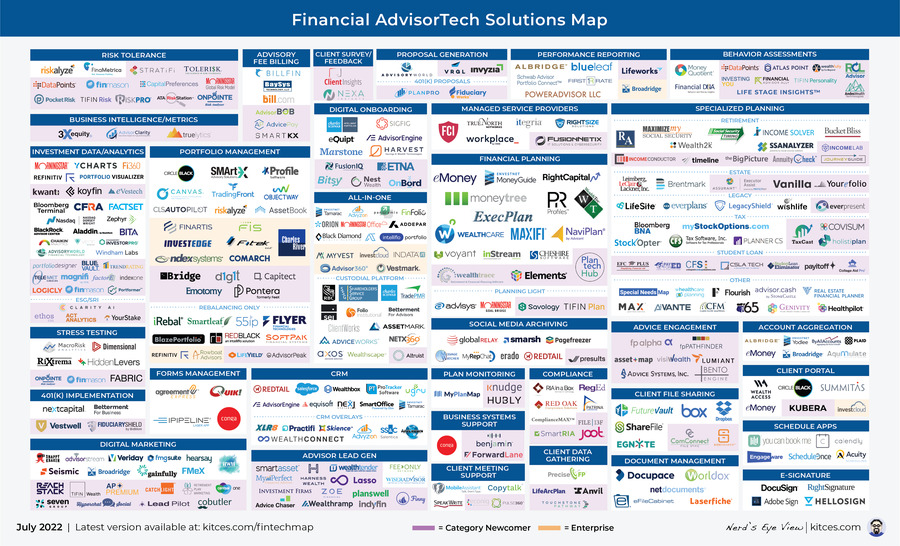

Be sure to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map!

AdviserTech companies that want their tech announcements considered for future issues should submit to TechNews@kitces.com!

When robo-advisers first launched nearly 10 years ago, they made the case that consumers were paying human financial advisers too much to allocate their investment portfolios, and that a robo-adviser could create a substantively similar allocation at a fraction of the cost — trying to set the going rate for building an asset-allocated portfolio at an AUM fee of just 0.25%. This would be relative to a typical adviser cost of a 1% AUM fee in the hope that consumers would flock to their platforms for the cost savings alone.

Yet what competing on price giveth, competing on price can also taketh away. It was just a few years later that Schwab decided to enter the fray, recognizing that robo-advisers were actually more of a DIY solution that threatened its self-directed brokerage platform than traditional advisers, and launched its own Schwab Intelligent Portfolios, or SIP, solution, which decided to take price competition one step further by launching and promoting itself as a free solution, and highlighting how consumers would be able to save even more wealth in their own pockets by eschewing the fees of competing robo-advisers altogether.

Except the media noted at the time that Schwab’s “free” robo-adviser wasn’t entirely benevolent. While Schwab wasn’t going to charge a robo-fee like its brethren, it did include a cash allocation that would vary from 6% to almost 30%. This would be allocated to a cash sweep with Schwab’s own bank, on which Schwab would earn profits that would allow it to make up for its foregone AUM fee. Not only was Schwab not necessarily free, but its higher-than-typical cash allocations would result in a “cash drag” on returns that could actually result in lower long-term returns (in addition to the fact that Schwab was making allocations to Smart Beta ETFs. These ETFs were "all ... either proprietary Schwab ETF products or ETFs from issuers that pay Schwab to use them"), even as Schwab maintained that its ETF and cash allocations were simply a result of a disciplined portfolio construction methodology.

But in June, the SEC charged Charles Schwab and its robo-adviser subsidiary. Schwab agreed to pay a whopping $187 million settlement “without admitting or denying the SEC’s findings.” This was after the SEC made its determination that Schwab’s cash allocations were not “set based on a disciplined portfolio construction methodology designed to balance performance with risk management” as its brochures claimed. Instead they “were pre-set for business reasons, and to compensate respondents for not charging an advisory fee” and that “Schwab management set the percentages of cash that each of the model portfolios should contain, and the portfolio construction team then applied its methodologies to create the rest of the portfolio, using the cash allocations as a constraint.”

This is important because, in the end, Schwab’s higher-than-usual cash allocations did adversely impact investors due to the cash drag. As the SEC noted, even Schwab’s own internal analysis had already found that “the cash allocations in SIP would reduce investors’ returns by approximately as much as advisory fees would have.” Schwab was continuing to advertise how “fees can eat away at your bottom line” and implying that its robo-adviser solution would generate higher returns as a result of the lack of fees without acknowledging that those benefits would be more-than-lost by the revenue and profits it was generating from Schwab Bank on the cash allocation.

This explains the remarkably large $187 million sum that Schwab ultimately agreed to pay in settlement with the SEC without even addressing Schwab's use of its own proprietary funds in its robo-models as well. This includes $45.9 million of profit disgorgement, $5.6 million in interest, and a $135 million civil money penalty, to be deposited into a fair fund that will be paid back to investors in the coming months. To put that in context, if Schwab’s robo yields an average of 0.25% on managed assets, a price similar to competing robo-advisers, the settlement is equivalent to all the annual revenue from nearly $75 billion of AUM. Schwab’s total AUM in its Intelligent Portfolios solution was reported last month at "only" $65 billion of AUM. If Schwab generates a 20% profit margin on its robo business, the settlement is the equivalent to the profits on $375 billion of robo-adviser assets. This means its $187 million payment may be close to wiping out all cumulative profits Schwab ever made on its robo-adviser since it was established seven years ago.

Notably, though, even as Schwab’s settlement with the SEC may wipe out years of profitability on its robo-adviser, it still can’t undo the competitive damage that Schwab caused in the marketplace itself. As Schwab’s growth, ostensibly driven in no small part by its years of aggressive advertising about its “free” robo-adviser, hobbled virtually every competing robo-adviser in the mid-2010s out of business. FutureAdvisor, Vanare, SigFig, Jemstep, Hedgeable, WiseBanyan and more all either were shut down or sold to traditional financial services firms after failing to compete successfully in the retail marketplace. Schwab Intelligent Portfolios alone is now larger than Betterment, Wealthfront and all the other stand-alone robo-advisers combined. In other words, while the SEC may have penalized the profits that Schwab generated from its “misleading” no-fee marketing against competing robo-advisers, it can’t bring back the competition that Schwab also decimated along the way.

This raises questions of whether Schwab will eventually face similar scrutiny for its other offerings, given that Schwab has similarly made a very public “pledge” that it does not and will not charge custody fees to RIAs and instead generates RIA custody revenue in a substantively similar manner to its robo-adviser (sweeping advisers’ client cash into its Schwab Bank offering, while also earning a piece of the underlying expenses of third-party products that advisers use and must pay to be available on the Schwab platform). Though while Schwab’s robo-adviser was itself an RIA — and the SEC’s charges focused on Schwab’s violations of the Investment Adviser Act requirement that investors not be misled — Schwab’s RIA custodial offering is technically a brokerage platform. This means Schwab doesn’t have the same obligation to its own RIAs, and it is up to the RIAs that use Schwab’s platform to make their own determination of whether Schwab’s revenue model is the right fit for their clients.

One of the biggest challenges that advisory firms face as they scale up the number of clients they serve is simply keeping track of the sheer number of advice opportunities that may exist at any time among their clientele. From reaching key ages where life transitions occur, to simply having life events happen, the ongoing flow of potential advice needs is what keeps the value of advice relevant to clients over time. However, it also requires an ongoing series of client meetings just to find out if there’s anything the adviser and client should be talking about now. This is remarkably inefficient, as it simultaneously means that often advisers are simply having a meeting for the sake of figuring out whether they even needed that meeting in the first place, and risks failing to be proactive enough to engage with clients at the exact moment they really need to meet, such as turning 65 and enrolling in Medicare.

Several years ago, Morgan Stanley made AdviserTech waves when it attempted to solve for this internally with a solution known as Next Best Action. The solution used AI to scan across the firm’s entire client base, watch for investment opportunities that might arise in their portfolios, and then prompt the firm’s brokers with investment ideas that they could reach out to those clients about. Ideally, Next Best Action could turn what historically was a very sales-based approach (here’s a product our company has for sale, let’s see which clients want to buy it) into a more client-centric approach (the software has identified something a client might want and need. Let’s reach out to show them how it solves their problem).

The caveat to Next Best Action, though, is that functionally it was arguably still more focused on product distribution than the advice itself. After all, a lot of the most meaningful opportunities to engage with clients have nothing to do with a change in their investment portfolio or their investments at all. Instead, they could tie to retirement planning, tax strategies, insurance or estate needs, or any of the numerous other domains of financial planning where advisers can add value.

In this context, it’s notable that last month, Bento Engine raised a $1.1 million round from a notable list of “RIA influencers” to power up its Next Best Action-style offering that is focused on evolving beyond just highlighting investment product ideas and toward supporting actual financial planning advice conversations.

At its core, Bento Engine integrates with the adviser’s CRM system, currently supporting integrations to Redtail, Wealthbox, Salesforce and Microsoft Dynamics. It uses a life in numbers framework that identifies common age-based milestones that may trigger planning conversations. From teenagers who could start their first Roth IRA with summer job money to benefit from multidecade compounding, to eligibility for IRA and 401(k) catch-up contributions at age 50 or HSA catch-up contributions at age 55, CRM data is mined to spot when clients are approaching those age milestones, and then prompts the adviser to reach out to the client regarding the planning opportunity. In turn, to support the outreach, Bento then provides prepackaged educational content, from articles to PowerPoint presentations and other visuals, that can be white-labeled to the firm for branding purposes, and used to help facilitate the conversation with the client.

Often financial planning advice doesn’t end in a product sale. The advice value-add is the conversation itself, which helps to introduce a new idea or concept to the client. Bento Engine’s approach is arguably less about a next best action per se, and more about facilitating the next best conversation that an adviser can have with the client to add value. This may or may not result in a subsequent action. In the end, the reality is that even when clients decide not to act, it’s still a meaningful moment in the advice relationship to have the conversation in the first place. Bento Engine is built to both prompt with its CRM integrations and help facilitate with its supporting educational materials.

In the long run, the real question for Bento Engine is whether it’ll be able to draw in enough data from adviser CRM systems to find the planning opportunities beyond just age-based milestones, which arguably advisers can build triggers to prompt themselves about already in existing CRM systems. This truly introduces new conversations, at the exact moment they’re most beneficial, that advisers would otherwise have only uncovered through the time-consuming traditional meetings-to-find-out-if-we-needed-a-meeting approach that tends to be less timely. This is also important, because, in the end, it means that Bento Engine won’t necessarily succeed by saving advisers time by cutting down on time-consuming conversations with clients, but instead by reallocating the advisers’ time to ensure the conversations they’re having are the most timely and relevant ones to be having at that moment.

The past decade has witnessed a veritable explosion of Adviser Technology solutions, transforming the space from a cottage industry of homegrown solutions (where an adviser has a problem, can’t find a solution, builds their own solution, starts selling their solution to other advisers, and ends up with a software company on the side) into a domain where advisers have half a dozen or more choices in every major category that can be woven together through the proliferation of APIs.

The good news in this proliferation of solutions is that advisers have more choice than ever about what solution they want to use. This means both a better chance to find software that’s the right fit for their firm, and ongoing competition that forces all players to make improvements to keep up with one another. The bad news is that the number of potential integrations that need to occur among an ever-widening breadth of players means that most tools don’t integrate as well as they could or should, as each company suggests that the other one should build the integration to their API. This often results in a finger-pointing stalemate and adviser data ends up splintered across multiple systems in a way that’s hard to maintain, often necessitates double data entry and prevents having one clear source of truth.

As a result of these integration challenges, in recent years the pendulum has begun to swing away from an ever-widening range of stand-alone best-in-breed solutions, and toward the rise of all-in-one platforms that aim to cover the full range of an adviser’s technology needs within a single platform. This means all the solutions are natively integrated with one another, and all the data is housed in one central location.

In this context, it was notable when last year, Pershing announced the launch of a new business unit, dubbed Pershing X, with the vision of building, from scratch, its own end-to-end advisory platform to become the next-generation all-in-one solution to compete with the likes of Orion, Morningstar Office, Black Diamond and Envestnet. It cited the challenges that even incumbent platforms like those have in weaving together data and workflows across disparate systems and sources. Now, after hiring up nearly 350 team members to build it, Pershing X has indicated that it expects to launch an initial Minimum Viable Product, or MVP, by the end of 2022 (while acknowledging that it will probably be two to three years before all the core features are fully built out).

From a pure technological perspective, Pershing’s ambitions to build a competitive full-scale adviser platform in just a few years is daunting in and of itself, especially given that Pershing is not exactly known for the pace of its technological innovation as the subsidiary of one of the oldest banks in the country. The company’s more modern lean-startup-style MVP approach is at least a promising step in the right direction.

But the bigger question from the adviser perspective is simply what Pershing’s end-game goal is for Pershing X in the first place. After all, the reality is that most advisory firms spend only a few percent of their revenue on all technology combined. This means even a robust all-in-one technology platform may command no more than 2 bps to 3 bps in software fees or as per-account, per-client, or per-account user fees when converted into a bps equivalent. This pales in comparison to the nearly 10X revenue that broker-dealers like Pershing can generate from the actual RIA custodial business, even as Pershing has emphasized that Pershing X is a separate division from Pershing’s custodial offering, and that Pershing X is expected to be a multicustodial platform not specific to just Pershing as an RIA custodian.

It's possible that the vision for Pershing X is to be less like a custody/clearing platform, which Pershing itself is, and more akin to Envestnet, where its technology facilitates the distribution of investment products. Pershing X can generate revenue-sharing payments for distribution, or even queue up its own Pershing-owned asset management solutions. Already, Pershing has tucked its own TAMP — Lockwood — under the Pershing X umbrella, and has signaled more broadly that model marketplaces and product provider lists (which often involve revenue-sharing from asset managers to the technology platform that facilitates them) could be part of its future.

Pershing X itself is simply emphasizing the potential time savings that it may be able to generate for advisers with a more efficient technology platform, highlighting Cerulli research that typical advisers spend only about 25% of their time meeting with clients. This is similar to Kitces Research also showing that the typical adviser only spends about 1/4 of their time actually meeting with clients). However, the reality is that the rest of an adviser’s time is more often spent on meeting preparation and follow-up, planning analysis for clients, business development activities, and internal team management time, none of which are particularly impacted by the technology that Pershing X is building. In the end, typical advisers spend barely 10% of their time on investment-related tasks in the first place, given the efficiencies that technology has already brought to the investment process that Pershing X is now trying to improve upon.

All of which means that in the long run, the real challenge for Pershing X may not even be its monumental task of trying to build an entire all-in-one adviser platform from scratch, but the end goal it's actually trying to achieve, given that there may not actually be much time savings on the table for Pershing X to generate for the typical adviser (that haven’t already been saved with technology or delegated to staff). Will Pershing X actually be able to save advisers meaningful time? Will it pivot to make the case that it can improve adviser margins by cutting down back-office staff time instead? Will Pershing X turn out to be more of an asset-management-distributed-via-technology play than an actual technology solution unto itself?

In the end, it will be hard for Pershing X to gain traction with advisers until it gets clear on the adviser problem it’s actually being built to solve.

Over the past 20 years, what were once two completely separate channels in the financial services industry — broker-dealers selling investment products to their customers, and registered investment advisers providing advice and managing portfolios for clients — have converged into one channel of financial advisers who typically receive ongoing (typically about 1%) fees to provide their clients an ongoing advice service. In turn, this has led to a decade of regulatory debates — from potential Dodd-Frank legislation to Regulation Best Interest — about how best to converge the differing suitability-versus-fiduciary regulatory standards of care that historically applied to brokers versus investment advisers, as the line between them becomes increasingly blurred.

At the same time, though, there is a third channel through which financial advice is delivered — to employer retirement plans — which is regulated by ERISA, which has its own fiduciary standard of care. As the broker-dealer and RIA channels have converged, so too has their delivery of advice to consumers via retail brokerage accounts and via their employer retirement plans. This has led to a series of Department of Labor fiduciary rule proposals over the past decade about how to modernize advice standards for both employer retirement plans, and rollovers from them to IRAs (and even rollovers from one IRA to another).

In December 2020, the Department of Labor finalized its latest rule — known as PTE 2020-02 — which prohibits both investment advisers and broker-dealers from receiving a wide range of conflicted compensation when engaging in retirement account rollovers unless they are eligible for a Prohibited Transaction Exemption, or PTE. This includes a number of key documentation and disclosure requirements, including not only the scope of the relationship and any potential conflicts of interest, but also specifically regarding the existing costs the client faces, how those costs would change if they begin to work with the new adviser, and a written justification of why engaging in such a rollover is in the best interest of the client even and especially in light of any additional costs that will be incurred. This is now required as of June 30, after the original rule’s 18-month delay to allow time for the industry to prepare for implementation.

Accordingly, this month RIA In A Box — which provides a software platform that helps RIAs manage their ongoing compliance obligations — announced a new partnership with InvestorCOM and its RolloverAnalyzer solution, just as the new PTE 2020-02 requirements take effect.

At its core, InvestorCOM’s RolloverAnalyzer is built to help fulfill the documentation and disclosure requirements when conducting rollovers, which it aids by extracting cost data on a prospective client’s existing employer retirement plan from available Form 5500 public filings, benchmarking those plan costs against similar plans, comparing those costs (and the associated services) to the adviser’s own costs and associated services, providing an explanation to the client of the recommendation, and then capturing the information shared and the subsequent recommendation that was made. Then RIA In A Box users will simply be able to access directly through their partnership.

Ultimately, the irony is that while financial adviser technology innovation has increasingly focused on financial planning and investment platforms, compliance arguably is one of the domains that has the most consistently repeatable processes that are most conducive to technology that automates or at least greatly expedites the process. RIA In A Box has long been effective at rolling out tools that directly address the compliance challenges that advisers face, and the integration with InvestorCOM’s RolloverAnalyzer — while not directly an RIA requirement, but a Labor Department requirement that RIAs must also now comply with — fits perfectly within RIA In A Box’s domain of making adviser compliance more efficient through technology.

Financial advisers don’t change their technology solutions very often. In fact, a recent Kitces Research study on AdviserTech found that only 4% to 8% of advisers were looking to change software in any particular category last year, which means on average, advisers only change any specific technology tool every 12 to 25 years.

This dynamic is further complicated by the fact that the adviser landscape is extremely fractured, with the overwhelming majority of advisers either entirely independent (e.g., as an RIA), or at least independent contractors affiliated to a centralized platform (e.g., most independent broker-dealers). Even the largest adviser enterprises — wirehouses, which have as many as 15,000 advisers — still only amount to barely 5% of the total adviser market of about 300,000 advisers.

The end result of this environment is that adviser technology companies looking to grow have to spend a lot of money on marketing just to reach prospective advisers, one individual or small firm at a time. It’s a pathway that’s often cost-prohibitive for most startups, unless they’re already raising outside capital to spend on marketing, or at least means that growth will be very slow, attracting one advisory firm at a time until the software company grows large enough over a span of years to crack into the enterprise marketplace.

This has made it all the more important that in recent years, a number of adviser events have arisen that give new AdviserTech companies a chance to showcase their wares and “be seen” by a wide range of individual advisers without necessarily being required to pay the steep price of pay-for-play presentation slots or exhibitor booths. Of course, conferences need to support their own economic model, which is typically supported by vendor sponsors, but startups that are required to pay top dollar to compete never get the opportunity to grow to the point that they can afford to pay for sponsorships in the long run.

Both Future Proof (a new adviser conference by a very experienced conference adviser team that’s looking to make a big splash as a new kind of “adviser festival”) and XYPN LIVE (the annual conference for XY Planning Network, an organization predominantly compromised of next-generation advisers serving next-generation clients) announced new demo events where emerging AdviserTech companies will have the opportunity to showcase their software to a wide audience without the requirement to pay a big sponsorship fee. Companies are only required to pay for their own travel and accommodations to participate in the event itself.

In the case of Future Proof, judges will select 10 AdviserTech companies to participate in a FinTechX Demo Drop. Submissions will be judged based on their “creativity, outside-the-box thinking, and the ability to create a real impact for the Future Proof audience.” XYPN’s AdviserTech Expo will highlight six finalists, and submissions will be judged by how well they support advice engagement (delivering financial planning advice to clients in a more engaging way). It is specifically limited to startups, that is companies that launched in the past 12 months, or that have less than $1 million of revenue, or an existing company with a substantively new offering that itself meets one of those criteria.

In both cases, the finalists that are selected will have an opportunity to showcase their software to the audiences of the respective conferences, which run from Sept. 11-14 for Future Proof and Oct. 8-11 for XYPN LIVE. Submissions were due by July 8 for Future Proof, and are due Aug. 1 for XYPN LIVE, with applications for XYPN’s AdviserTech Expo here.

As the first wave of baby boomers began to reach retirement and Social Security age in the mid-2000s, the financial advice industry increasingly began to focus on retirement planning and the assets under management model. The shift made sense; just as bank robber Willie Sutton famously robbed banks because “that’s where the money is,” advisers increasingly focused on baby boomer retirees and helping them with their retirement portfolios because that’s where the money was (with 85%+ of investible assets at the time in the hands of retiring baby boomers and their already-retired parents in the silent generation).

Yet at the same time, there was growing concern that eventually, the older generations will pass away, and the adviser community had no established relationship with the next generation of clients (Gen X and millennials), inhibited primarily by the fact that the younger generations were unprofitable to serve because they didn’t yet have substantive portfolios and the complexity that comes with more significant wealth, such that they didn’t have the complex needs to pay what it takes to have and get value from a financial adviser relationship.

The reality, though, is that while Gen X and Gen Y clients may not yet have substantial portfolios, their financial lives are not simpler, they just have different (non-investment-related) complexities. As a result, the younger generations were interested in, and willing to pay for, a relationship with a financial adviser for help with the complexity in their lives. They simply needed a different way to pay for advice than the traditional AUM model, leading to the rise of the monthly subscription fee for financial planning, from adviser networks for subscription fee planning like XYPN, to scaled RIAs like Facet Wealth also championing the model, and technology platforms like AdvicePay facilitating the payments and associated compliance obligations.

Of course, not everyone even wants a financial adviser to deal with the financial complexity in their lives. Some are fine using the available do-it-yourself technology tools or simply doing their own research on the internet to handle their own situations. Others would prefer to pay someone else to help them figure it out and want a full financial planning relationship. There’s also a midpoint of people who may want to engage in more piecemeal advice as needed — dubbed Validators by Forrester Research — who right now tend to buy hourly as needed when they have a complex issue and a tentative plan, and need an expert to validate their course of action.

In this context, it was notable that Fruitful emerged from stealth mode with a big $33 million Series A round to fuel a combination of a financial planning app (to be launched on smartphones this fall) paired with access to a CFP professional who will serve as a “guide” to provide ongoing financial advice, for about $100 per month. This effectively appears to aim at a midpoint between pure DIY tech, with apps that are free or have a very low nominal cost, and full-on subscription financial planning, from firms like Facet or advisers at XYPN, which increasingly is pricing at $200 per month and up.

As with most other low-cost, highly scaled advice solutions that have entered the marketplace in recent years, the immediate question from the adviser community has been, “How many clients will a Fruitful CFP guide actually be able to support?” After all, at an annual fee of $1,200, each CFP guide would ostensibly need 300 to 400 or more clients to be able to meet typical adviser-industry revenue/adviser productivity metrics. Would Fruitful ostensibly be expected to have even better numbers as a venture-funded technology company? At 2,000 working hours per year, of which even a very efficient adviser would likely struggle to maintain more than 50% to 60% of their time in client meetings (given the need for training, professional development, management, some level of operations/administrative and compliance work), that suggests that at best, a typical Fruitful client may only get three to four instances per year of engagement with their CFP guide.

To the extent that Fruitful’s app can also add meaningful value, arguably consumers may still be happy with the service even with fewer hours from their CFP guide in any particular year. Though to the extent that competitors like Personal Capital gave their app away for free — because ironically, it was so popular the app was more effective to use as a free lead generation tool than it was to monetize by charging for it — arguably there’s only so much room for Fruitful to maintain its $100 per month fee via an app when most such tools charge less than $100 per year if anything at all.

The added complication for Fruitful is that to the extent it’s serving validators who tend to engage for just a few hours of advice here and there as needed, validators can already engage in piecemeal hourly advice from a wide range of advisers for a going hourly rate of $200 to $300 per hour. This means that Fruitful’s pricing structure for validators would actually be more expensive for them than simply hiring an adviser as needed on an ad hoc basis, especially in the years where fewer advice questions crop up in the first place.

In other words, the irony is that while on the one hand there’s clearly a market for some low-priced technology to support the do-it-yourselfer, and a market for higher-priced advice for those who have more complexity and want an ongoing advice relationship (e.g., even Facet’s “highly scaled” model runs at $1,800 to $6,000 a year), it’s not so clear whether the middle will be viable. This is because client acquisition costs may be prohibitive when the typical advisory firm spends $3,000 or more to acquire a client. Also, Fruitful’s cost may not even be competitive for validators, who could just pay an hourly rate as needed, and also simply by virtue of a service that is priced for an ongoing relationship but would only have room for three to four client interactions per year. By comparison in the world of physical fitness, DIY consumers can look up exercises for free on YouTube or pay a few dollars per month for an exercise app, or hire an ongoing personal trainer to work with them several times per week to keep them on track for their goals; but not many people pay a coach an ongoing fee for an ongoing relationship, but just meet an hour here or there.

Of course, it’s still very early for Fruitful, and the company has substantial funding to give it room to iterate and decide whether it wants to move further upmarket with higher fees for a deeper relationship or further down-market with an even more scaled offering that relies primarily on its app instead of CFP guides. Nonetheless, Fruitful may well prove to be a good test case for the feasibility of an ongoing recurring revenue model to serve not the do-it-yourselfer or the deep-relationship delegator, but the broad base of validators who still struggle to engage with traditional financial advisers.

In the meantime, we’ve rolled out a beta version of our new AdviserTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map with several new companies (including highlights of the Category Newcomers in each area to highlight new FinTech innovation).

So what do you think? Will Fruitful be able to find a market and scale with validators paying just $100 a month, or will it have to go further up- (or down-) market instead? Will Schwab’s “free” RIA custodial offering attract the kind of regulatory scrutiny its “free” robo-adviser faced? Will Bento Engine find traction with a “Next Best Conversation” solution for advisers?

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter @MichaelKitces.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound