The April edition of the latest in financial #AdvisorTech kicks off with the news that RIA custodial platform Altruist has built its own full self-clearing capabilities, while nearly simultaneously buying competing (not-self-clearing) custodian Shareholders Service Group. Given the heavy costs of being in business as a self-clearing custodian, this suggests that Altruist has reached a tipping point in terms of growth and scale and intends to push that growth further, given its acquisition of SSG as it seeks to grow its market share as an alternative to the “Big 3” (or part of the new “Big 4”) custodians of Schwab/TDAmeritrade, Fidelity and Pershing.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month’s column, as well as a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

Be certain to read to the end, where we've provided an update to our popular Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory.

AdvisorTech companies that want to submit their tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to TechNews@kitces.com.

Launching a custodial platform for RIAs is a difficult process. Custodians incur significant expenses for the privilege of holding client assets for financial advisors, including the costs of regulatory compliance, meeting capital requirements, staffing for the service demands of advisors, and the investment in all the technology that underlies the process of storing, moving and trading client assets. As a result, custodians need to achieve significant scale — often at the level of tens or hundreds of billions of dollars in assets — just to operate as a sustainable business.

Consequently, firms that do want to get into the custody business generally need to find a way to achieve the required scale for doing so before launching a custodial offering. The irony is that none of today’s leading Big 4 RIA custodians were able to scale up solely by being RIA custodians. Schwab, TDAmeritrade and Fidelity originally functioned as retail broker-dealers until they had the revenue and resources to add RIA custody as a line of business, while Pershing served independent broker-dealers at scale before expanding into independent RIA custody as well.

More recently, a newer generation of smaller, second-tier custodians (after the Big 4) have served RIAs as introducing broker-dealers — essentially a technological and/or service overlay on top of an existing third-party custody and clearing broker. They can take orders for trades, money movements and account opening, then passes those instructions along to the real custodian, which executes the actions itself. The introducing broker-dealer model has allowed investment technology platforms — including robo platforms like Betterment, Wealthfront, Robinhood, Stash and SoFi, as well as RIA servicers like SSG, TradePMR and Altruist — to build their offerings on top of technology-friendly custodial platforms like Apex Clearing, First Clearing and Pershing, without needing to first achieve the huge scale necessary to build and sustain a full-service custodial offering.

The introducing broker-dealer path has significant advantages for firms that want to specialize in RIA custody from day one rather than serve both advisor and retail channels as the mega-custodians do. Rather than needing to build an entirely different business model as a retail broker-dealer before branching out into custody, those that serve as introducing broker-dealers can simply focus on building the type of custodial offering they want to build. The drawback, however, is that introducing broker-dealers don’t own the custodial technology they rely on, but instead essentially license it from a behind-the-scenes custodial partner like Apex Clearing. That lack of ownership can result in missing some significant revenue opportunities that true custodians can realize, as the core economics including spreads on cash sweeps, interest from margin lending, payment for order flow, and more recently fully-paid lending (i.e., posting custodial assets to lend to short sellers in exchange for cash collateral, which the custodian can then invest in short-term securities like Treasury bills for additional income), have to be shared and split between the introducing broker-dealer and the underlying clearing firm. This means that once introducing broker-dealers achieve the level of scale where building their own custodial offering would be less costly than paying a firm like Apex Clearing to provide it, they are highly incentivized to do so. Indeed, numerous firms that once used Apex’s custodial platform, including Wealthfront and Robinhood, eventually became self-clearing custodians using their own internal clearing broker-dealer.

In March, RIA custodial platform Altruist became the latest firm to break away from Apex Clearing and launch its own self-clearing custodian. Less than two weeks later, Altruist made more headlines by announcing its acquisition of competing RIA custodian Shareholders Service Group, or SSG. With these moves, Altruist has demonstrated that it believes it has achieved the scale necessary to exist as a self-clearing custodial platform, which gives it even more capability to scale up further and boost its market share in the competitive RIA custodian space.

For Altruist, the benefits of going self-clearing are self-evident. It gets to stop paying platform fees to Apex Clearing to provide its behind-the-scenes clearing services, and starts benefiting from all the revenue provided by cash sweep spreads, payments for order flow, and fully-paid lending revenue (which Altruist CEO Jason Wenk confirmed will be used to generate revenue for the platform).

The decision to buy SSG is perhaps a bit more nuanced. Similar to Altruist before its self-custody launch, SSG is an introducing broker-dealer that overlays a separate clearing firm, in this case Pershing instead of Apex Clearing. It has proven to be highly popular with RIAs on its platform as a result of its reputation for excellent customer service, along with its friendliness toward smaller RIAs. This leaves Altruist with the awkward choice of either offering two competing custodial options — one of which is built on Altruist’s in-house clearing custodian, and the other one on Pershing — or incentivizing SSG advisors over to its own platform, where it can earn revenue on client assets (and risking inconveniencing or outright angering existing SSG advisors, who would bear most of the headache of learning new systems). For now, Altruist has made it clear that SSG advisors can expect “zero disruption to existing services.” At the same time (and on the same webpage) it makes overtures to advisors on SSG’s platform, suggesting that transitioning to Altruist will get them “the benefits of a modern, all-in-one custodian.” This makes it seem at least reasonably likely that in the long run the two entities will merge into a single platform. What else can advisors expect when a self-clearing platform that built its own in-house technology acquires a fellow RIA custodian that is not self-clearing and did not build its own in-house technology?

For now, though, what the acquisition seems to really be about is simply further boosting the scale that allows Altruist to benefit from its self-clearing custodian capabilities. Before the deal, both Altruist and SSG reportedly had around 1,600 advisors on their respective platforms. The combined entity, with over 3,000 advisors, will now be the third-largest RIA custodian in advisor head count behind the Schwab/TDAmeritrade and Fidelity behemoths, although in asset totals, the firm still lags behind Pershing, which has fewer but much larger firms on average than Altruist or SSG.

The remaining question, then, is where Altruist goes next to continue its growth. SSG was an enticing target given its similar focus on small to medium-sized RIAs while having a gap in self-clearing and in-house technology that Altruist could solve. However, the remaining options for a custodial acquisition aren’t as clear a fit. This means that in order to keep scaling up, Altruist will need to capture a meaningful proportion of new or breakaway advisors coming into the market, or lure existing advisors away from competing custodians — a proposition that, beyond the current opportunity to peel off former TD Ameritrade advisors looking for alternatives to Schwab’s custodial platform with the pending Labor Day integration transition, traditionally has been an uphill road toward growth given the pain of switching all of an advisor’s clients from one custodian to another. Still, given the popularity of its technology and custodial tools — in the 2023 T3/Inside Information Software Survey, Altruist and its new subsidiary SSG ranked No. 4 and No. 1 in user ratings respectively, with Equity Advisor Solutions and TradePMR’s Fusion platform slotting between the two — and the inroads it’s already made to scale up to the point where self-clearing custody was even a feasible option, Altruist has made a clear argument for itself to reconstitute the Big 4 of RIA custodians (replacing TD Ameritrade as it’s integrated into Schwab, alongside Fidelity and Pershing).

The early 2010s saw the rapid emergence of direct-to-consumer robo-advisors, which marketed themselves as offering customers diversified, asset-allocated investment portfolios for as little as 0.25% of assets under management compared to the standard 1% charged by a human advisor. The purported reason that they could charge rock-bottom fees was that their technology could streamline account opening and money movement by offering paperless account opening years before most RIA custodians had that ability. They could also largely automate the investment management process itself using ETF model portfolios and algorithmic rebalancing engines, eliminating a significant amount of the manual and inefficient processes of human financial advisors.

What the early direct-to-consumer, or D2C, robo-advisors didn’t realize, however, was that account opening and portfolio management aren’t the biggest drivers of costs for human advisors that cause them to charge what they do. Instead, it’s the high cost of acquiring clients (as much as $4,000 per client for an established financial advisor) that largely sets a floor on advisory fees. For all the disruptive potential of the technology deployed by robo-advisors, it still failed to solve this cost-of-acquisition problem — which meant that by 2015 or so, many of the early D2C robo-advisors were struggling since their rock-bottom fees couldn’t cover the costs needed to entice new clients onto their platforms to begin with. At the same time, institutional giants like Schwab and Vanguard launched their own competing robo-advisors, backed by the huge scale and more importantly the name brands and existing distribution systems of their firms, which squeezed stand-alone robo-advisors even more. Over the next several years, the industry went through a shake-out period in which some robo-advisors were acquired or shut their doors like RobustWealth, Motif Investing, Jemstep, Upside Advisor and Vanare. Others were forced to adapt however they could to stay alive, such as Betterment launching its Betterment for Advisors and Betterment 401(k) solutions to tap into the advisor markets it had once loudly sought to disrupt.

One case in point on how robo-advisors struggled, then evolved, over the past decade is FutureAdvisor. Founded in 2010, FutureAdvisor had some early traction in asset growth, but was a clear No. 3 behind its primary competitors Betterment and Wealthfront in asset growth; they outgrew FutureAdvisor and then out-raised it with outside capital to keep their lead. By 2015, the writing was on the wall. Being distantly behind its competitors in what was likely to be a winner-take-all race. FutureAdvisor wouldn’t be able to survive on its own much longer. Luckily, however, it found a whale of a suitor in the massive institutional manager BlackRock, which bought FutureAdvisor for $150 million in August 2015. But rather than continuing to focus on retail customers, BlackRock instead pivoted FutureAdvisor into a technology offering for institutional firms like banks (e.g., BBVA and RBC, which both signed on to provide digital advice powered by FutureAdvisor) to use with their clients. At its core, BlackRock saw in FutureAdvisor not just a D2C investment management business, but the early stages of a model-based investment approach. It could become a means to distribute Blackrock’s iShares funds — with which it populated FutureAdvisor’s model portfolios — foreshadowing the rise of the model marketplace that would come to dominate investment management technology within just a few years.

But even though FutureAdvisor’s focus under BlackRock largely shifted to being a B2B robo-advisor for advisors, it retained its original retail offering as a sort of vestigial remnant of its D2C past. The retail side of the business survived — albeit overshadowed by its institutional counterpart — perhaps in part because it was such a small part of the multitrillion-dollar BlackRock machine that there was little pressure to do anything with it. That is, until February of this year, when BlackRock announced that it would be closing FutureAdvisor’s retail business, with RIA Ritholtz Wealth Management agreeing to take on the robo-advisor’s clients.

The deal makes sense for two main reasons. First, under BlackRock, FutureAdvisor didn’t seem to have much more success attracting new clients than it did before the purchase. Its growth in AUM from $600 million at the time of the acquisition in 2015 to $1.76 billion as of April 2022 appears to be heavily attributable to market growth combined with account contributions from its existing clients, and BlackRock seemingly had little interest in putting resources toward acquiring new retail clients. It simply didn’t make sense for BlackRock to retain a business it clearly had little interest in growing. Second, Ritholtz — as an example of an RIA that has successfully implemented robo technology via its Liftoff platform, due in no small part to the marketing machine of the many blogs, books, and TV appearances from Ritholtz’s principals — seems positioned to serve FutureAdvisor’s clients sustainably and can benefit from the increased scale and possible new technology that comes with the FutureAdvisor clients.

Notably, though, while the financial details of the deal weren’t made public, a sales price of two times revenue based on FutureAdvisor’s 0.5% management fee and estimated $1.76 billion AUM suggests Ritholtz would have paid around $17 million for FutureAdvisor’s clients, On its surface, this represents a nearly 90% loss on BlackRock’s original investment of $150 million. However, given that BlackRock’s original acquisition was never really about the retail business at all, but rather about using the platform’s technology to distribute its iShares ETFs via model portfolios embedded within FutureAdvisor’s technology to financial institutions and their clients, it’s certainly possible that the deal still turned out well for the firm. It may still continue to pay off for BlackRock on the institutional side of its business, and considering the ongoing success of the model marketplace channel in recent years, it could have already realized a healthy return on its investment.

Ultimately, however, the FutureAdvisor story provides yet another data point that shows how, rather than disrupting the financial advice industry, robo-advisors instead served to augment it in different ways, whether that was serving as a means to distribute iShares ETFs for BlackRock or as a way to efficiently serve smaller clients when the problem of how to attract those clients has been solved for RIAs like Ritholtz.

Advisory firms that use recurring revenue models (e.g., ongoing AUM or monthly retainer fees) have a strong incentive to keep their clients satisfied. A satisfied client is one who’s more likely to stick around for the long term. If they’re really happy, they just might refer their friends and family members to the advisor as well. And in a world where the costs of client acquisition in terms of both hard dollars and time spent can be a significant expense for advisory firms, having a nearly free source of incoming clients (with zero hard-dollar cost and a minimal time commitment from the advisor outside of doing the work for their existing clients and asking those clients for referrals to begin with) can be an incredibly valuable source of business growth.

In the traditional business world, client/customer feedback surveys help to gauge levels of satisfaction at a particular point in time, which repeated over time can track overall satisfaction levels to assess how the firm is broadly doing at serving its client base. It also flags potentially unsatisfied clients who might be at risk of leaving. Yet although this practice can be effective for monitoring overall client satisfaction levels for the purpose of client retention, it doesn’t work as well for determining whether clients are satisfied enough that they will go on to make referrals. It’s one thing for a client to be satisfied with an advisor’s services to the point where they won’t shop around for a new advisor but it’s quite another for them to be meaningfully engaged — that is, to be so actively utilizing the advisor’s services that they’re proactively sharing that client experience with others, thus becoming a source of referrals on the advisor’s behalf.

Research has shown that one of the biggest drivers of client engagement is simply whether the client feels as though the advisor hears, understands and meaningfully responds to the client’s needs. To this end, AdvisorTech companies like Absolute Engagement and Nexa Insights have developed survey tools that help advisors go beyond basic client satisfaction and tap into the real concerns that clients have, so the advisor can respond in a way that deepens the relationship and drives better engagement. The caveat, however, is that what’s top of mind for the client may be constantly evolving, and however effective a survey is at delving into the client’s needs, it can only tell an advisor what the client’s needs are at that time. A survey sent once a year won’t necessarily be helpful in deciding on discussion topics for a review meeting that’s six months away. Yet the time it takes for advisors to send out surveys, review feedback and respond accordingly means that soliciting feedback more than once or twice per year has never really been an option on a firmwide scale. Until now.

Recognizing this need for a way to efficiently ask for and respond to client feedback in real time, Absolute Engagement rolled out a new platform called the Absolute Engagement Engine that seeks to embed moments of client feedback more deeply within advisors’ ongoing workflows and client communications. In other words, rather than traditional feedback surveys, which are typically sent one-to-many at a single point in time, the engine aims to deliver one-to-one feedback at all the ongoing times that may matter (i.e., any time the advisor is otherwise interacting with the client).

In practice, the Absolute Engagement Engine platform seems to work by inserting survey-style and open-ended client engagement questions within various advisor processes — such as an initial contact form for prospective clients or a Calendly link for existing clients to schedule their review meetings — and then automatically generating follow-up actions and responses based on that feedback. For example, a survey tool used when scheduling an annual review meeting could then automatically populate an agenda for the meeting that includes the topics that are top of mind for the client based on their feedback. This ensures the advisor will address the areas that are most directly relevant and engaging to the client, while eliminating much of the manual work of sending out surveys, reviewing feedback and integrating the results into the advisor’s workflow.

Advice engagement has been one of the hottest and most rapidly-expanding categories of the AdvisorTech landscape over the past two years as advisors seek to keep clients engaged in the ongoing advice process. However, many of those advice engagement tools are about delivering advice in a way that is more engaging to clients, while the Absolute Engagement Engine works in the opposite direction. At its core, it’s really about keeping advisors engaged with what’s important to their clients so they can address those issues in real time. Although the problem of understanding what’s important to clients seems easy enough to solve by just asking them, the reality is that finding a way to systematize that client feedback process on an ongoing basis for an ever-growing number of clients is a real challenge for the modern advisory firm to solve at scale. This is the exact hole that Absolute Engagement is aiming to fill.

The roots of today’s financial planning software go back to the days when most financial advisors were primarily product salespeople. One of the methods those advisors used to sell products like life insurance and mutual funds was to show their prospective clients the gap between what they currently had and what they needed, which could be filled with whatever product the advisor was selling. The earliest financial planning software came about as a tool to conduct needs analysis and calculate and illustrate those gaps, and as such were generally designed to be used just once in the client relationship — i.e., when the advisors were pitching their product and needed to get the sale.

As the industry shifted from being product-centric to being more advice-centric, the software used by advisors evolved in kind. Financial planning software platforms built out more holistic planning tools, reflecting the need for advisors to develop deeper relationships with clients and deliver more comprehensive advice to demonstrate a value proposition beyond just the investment portfolio, and to support a more ongoing recurring-revenue-based relationship. But most of the financial planning was still concentrated around one or two meetings each year, an intensive process that entailed gathering and updating client information, rerunning projections, and creating and presenting “the (updated) plan” that encompassed the advisor’s latest observations and recommendations. So even though financial planning software had evolved to support ongoing relationships (e.g., by making it easier to update client data from one meeting to the next), each plan that the software produced was still essentially a new one-time projection, and the software’s output — and any recommendations stemming from it — would stay fixed until the next review meeting.

In more recent years, there has been a shift in focus from creating “the plan” to a process of continuous planning, as advisors feel more pressure to provide year-round value outside the annual or semiannual review meeting, and also recognize that clients’ financial lives evolve between review meetings in ways that would benefit from more advice in real time. This has opened the door to a rapidly growing category of advice engagement tech tools designed to keep clients engaged in the ongoing advice process and fill in the gaps between comprehensive plan updates that aren’t addressed by traditional financial planning software.

In this context, it’s notable that Lumiant, an advice and client engagement platform founded in Australia to create these types of higher levels of ongoing engagement with clients (and specifically with both members of the client couple, to engage what is often one less-engaged spouse), Lumiant raised $3.5 million in seed funding to support its expansion in the U.S. and build out its mobile app as it seeks to take this approach even further. Notably, the funding from this round came not from venture capital sources but from two of Lumiant’s large enterprise users, Australian advisory firm Invest Blue and U.S.-based Savant Wealth Management.

From an advice engagement perspective, Lumiant aims to differentiate with a more values-based approach to help clients define what really matters to them — an area that’s often cited for its importance in financial planning, but which few technology tools exist to address. To this end, it includes surveys and discovery tools to address nonfinancial areas of importance, values and goals for the client. But beyond these discovery tools, Lumiant’s product also includes a growing suite of other tools that are likely more familiar to financial advisors. This includes an investment risk tolerance survey, account aggregation and data collection tools, a client dashboard, a document vault and now a growing breadth of retirement planning and Monte Carlo projections. So although Lumiant frames its product as an advice engagement tool, the sheer breadth of its functionality raises the question of whether it is intended to work alongside an advisor’s other software tools or as a more end-to-end solution to replace them entirely by combining financial planning software and ongoing advice engagement into a single platform.

Notably, Lumiant’s end-to-end platform approach is a departure from how other advice engagement tools have approached the market. Many of these startups have found success by focusing on a specific need or segment of the planning process, so that they can augment an advisor’s existing financial planning software tools rather than competing with them. This makes sense given that financial planning software is one of the highest-rated software categories in terms of satisfaction. Kitces Research On Advisor Technology Use has found that barely 5% of advisors are looking to make a switch from their current software (and of those who do intend to switch, most already know which platform they plan to switch to), meaning that any new entrants into that category face a heavy lift in convincing advisors to go through the pain of transitioning from one platform to the other (especially given the lack of data migration capabilities when switching from one financial planning software to another).

By themselves, Lumiant’s values discovery and engagement tools could likely slot in with an advisor’s existing technology, alongside other behavioral assessment and values-discovery platforms like Money Quotient or ROL Advisor. But adding on all of its other tools, which are likely redundant with other software that advisors are already using for financial planning, raises the stakes for advisors considering Lumiant, since now they need to evaluate each of those tools versus its incumbent and decide whether it’s really worth it to switch (or to simply own, and pay for, multiple tools fulfilling the same function). Ultimately, Lumiant may find it more difficult to gain traction in its current end-to-end form than if it were to stick to one or two core functions and not compete with the rest of advisors’ tech stacks.

This is reminiscent of how, in investment management, advisors must generally choose between using separate tools for trading, performance reporting and billing versus having one all-in-one solution that covers each step in the process. It’s worth noting that there is no single dominant approach, with a best-in-breed combination of individual tools, and all-in-one solutions both gaining widespread adoption throughout the industry. However, the all-in-one tools that have been successful, like Orion and Envestnet, generally found their initial success as more focused solutions, building out new functions as time went on to encompass more of the investment management process. In that vein, the question is whether the first all-in-one financial planning and advice engagement platform will evolve out of an existing tool that has already gained widespread traction, or whether a newcomer like Lumiant can really break into the market with all of the features built in and actually persuade advisors to change out everything they’re currently using for financial planning for something new.

One of the key parts of financial planning is creating a detailed portrait of a client’s financial picture — their balance sheet, spending, investments, taxes, insurance, estate plan and everything else that contributes to their ability to meet their long-term financial goals. Much of the information needed to create this picture comes from primary source documents such as investment statements, tax returns, insurance policies, wills and trusts. So reviewing these documents to find the key information relevant to clients’ financial planning needs traditionally has made up a nontrivial part of the analysis stage of the financial planning process.

The problem, of course, is that many of these documents can be incredibly long (tens or even hundreds of pages) and complex, such that reviewing them can take an enormous amount of the advisor’s time. Education and experience can help streamline the process somewhat. For example, getting training on and knowing what key information to look for in clients’ tax returns or in their estate planning documents can help advisors zero in quickly on the important parts without flipping through the entire document. But even then, the information needs to be reviewed, analyzed and put into the context of the client’s financial situation, a process that has traditionally been largely manual and time-intensive.

One of the pioneers of automating the process of turning raw primary document data into an analysis of key information was Holistiplan, which launched its tool in 2019 that reads a client’s scanned or uploaded tax returns, summarizes the key information, and provides individualized planning recommendations based on the data it finds. Holistiplan solved such an obvious pain point that it rapidly gained widespread adoption, with the 2022 Kitces Research on the Financial Planning Process showing a whopping 79% adoption rate among advisors who use specialized tax software.

With the success of Holistiplan, it was only a matter of time before other providers emulated that approach for other financial planning topical domains. One of the most obvious areas of need was in clients’ estate planning documents, which are not standardized and often full of legalese that can be hard for non-attorneys to decipher. In May 2022, AI-driven fintech provider FP Alpha launched an estate planning tool that, similar to Holistiplan’s approach to tax returns, will read clients’ wills, trusts, power of attorney documents and health care directives, and generate a simple snapshot document summarizing the key components of their estate plan. The tool also includes an Estate Planning Lab that allows advisors to model different estate planning scenarios.

The launch of FP Alpha’s estate planning tool generated a lot of buzz at the time as the “Holistiplan of estate planning,” but unlike Holistiplan, it wasn’t released as a stand-alone solution. Instead, it was bundled alongside FP Alpha’s suite of other AI-driven planning tools (including tax planning, insurance and prospecting tools), which meant that advisors were required to buy the whole package even if they were only interested in the estate planning solution and weren’t necessarily ready to bite off more software changes. This led to questions about whether FP Alpha would eventually feel pressured to spin off the estate planning module as a stand-alone offering.

Those questions were answered at the T3 Conference in March, when FP Alpha founder and CEO Andrew Altfest announced that the Estate Module will be available for purchase as a stand-alone product. Reading between the lines, it’s clear that demand for the estate planning solution on its own outstripped the demand for FP Alpha’s full suite of products, leading the company to offer the estate planning tool on its own. The tool gets the product’s foot in the door with advisory firms that could be convinced to spring for the whole bundle in the future.

In the vein of going deeper on primary document reviews, another feature announced by FP Alpha at this year’s T3 Conference was a new P&C Insurance Snapshot. Similar to the Estate Planning Snapshot, P&C Snapshot will automatically read clients’ property and casualty insurance documents (e.g., home, auto, and umbrella liability policies), generate a summary and highlight any potential gaps in coverage that should be addressed. This is helpful to a certain extent, though its value may be limited by the fact that advisors don’t typically spend that much time reviewing clients’ property and casualty insurance to begin with (the latest Kitces Research on Advisor Productivity showed that only 46% of advisors do any evaluation of P&C insurance for clients, compared to 81% who cover estate planning and 90% who address income tax planning).

The takeaway is that while there’s clearly value for advisors in technology tools that can automatically read and summarize often-length primary source documents — namely tax returns, estate documents and P&C insurance policies to date — there isn’t necessarily burning demand for those tools in all areas. Not all advisors cover all of these domains in the first place (either at all, such that they wouldn’t buy the tool, or potentially for some clients but not all, such that they’re not willing to pay the full software fee). This means that advisors who may be willing to pay for a stand-alone tool like Holistiplan or FP Alpha’s estate planning module may not yet be ready to pay for a whole suite of document analysis (or other more holistic advice) tools offered by FP Alpha. Of course, that assumes that advisors are even ready to trust AI tools enough to substantively hand over the process of reviewing and analyzing primary source documents from clients in the first place.

Still, in terms of real-life use cases of AI technology for financial advisors, tools that can read and analyze financial documents have the potential to be a major time-saver, even if they just flag areas where advisors can dig deeper and address issues instead of needing to be fully relied upon for recommendations. Much of the opportunity of AI when it comes to financial advisors is not in replacing the advisor, but in the ability to augment advisors’ work by automating back and middle office functions that deal with complex financial planning tasks — in essence, replacing not the financial planner, but instead the administrative assistant and the paraplanner supporting the advisor. By showing advisors how they can resolve major pain points like digesting reams of estate planning documents (and assuming it can create an accurate and reliable output), perhaps tools like FP Alpha’s can get more advisors to come around to the idea that AI tools aren’t coming for their jobs, but are rather setting up to allow them to do their jobs better (which it would then be in a position to monetize with its broader suite of AI-driven tools).

One of the enduring legacies of the early, product sales-driven days of the financial advice industry is that it remains largely focused on the asset side of the balance sheet. Clients have always needed debt products as well, such as mortgages, credit cards and business loans. But in the days when financial advisors were mainly concerned with selling mutual funds and life insurance to growth a client’s assets, it was usually bankers and mortgage brokers that consumers turned to for guidance on obtaining and structuring debt. Since then, even though the advice industry has largely shifted from a product-centric to an advice-centric model, the emphasis is still often on saving and accumulating assets to build wealth rather than managing the liabilities side of the client’s balance sheet.

A more holistic view, of course, recognizes that debt matters, too, since each dollar added to the asset side has the same impact on net worth as a dollar removed from the liability side. Arguably, relieving obligated debt payments can be an even greater driver of positive optionality in clients’ available financial planning choices. While the traditional clients of financial advisors don’t typically have much debt to speak of (e.g., high-net-worth retired clients with paid-off houses), a growing base of younger clients from the Gen X, millennial, and even Gen Z generations are coming onboard with high debt loads from student loans and mortgages and sometimes even credit cards as well. This presents a significant opportunity to advisors who can best advise on how to manage their debt, given that when a client’s liabilities reach into the mid-six-figure range (as is the case for many professionals with college and/or graduate school debt plus mortgages), helping them save merely 1% to 2% in interest can add up to as much or more than the advisor’s entire annual fee.

But in practice, advisors often still only pay lip service to client debt management while providing basic advice that starts and stops with “pay off your highest-interest loans first.” In reality, there are many more ways that advisors can help clients structure and optimize their debt. In much the same way as advisors can help clients find higher interest rates on their cash deposits (and use tech tools like MaxMyInterest, Flourish Cash and Advisor.cash to help them do so), advisors can also help clients find lower rates on their debt by refinancing or shopping around for new debt. In other words, rather than solely managing clients’ assets, advisors can effectively put their clients’ liabilities under management as well.

One startup seeking to capitalize on the advisor opportunity presented by credit/debt management is Sora Finance, which recently announced a $3.9 million fundraising round. Sora’s value proposition is threefold: putting together a picture of clients’ debt situations to facilitate planning, finding the best rate on new debt (or opportunities to refinance existing debt at new rates) via partnerships with financial institutions, and seamlessly facilitating the process for advisors’ clients to apply for and close on new loans, all within its platform.

Sora’s platform is one of the few tools out there (along with Advisor Credit Exchange, which has also integrated its solution with Envestnet) for advisors who want to take a more active and engaged role in managing client debt — which, given the potential for hard-dollar client savings, may be an attractive option for advisors who want to go deeper into that realm. The main question, however, is how much advisors really dowant to be involved, with debt management being just one more item on top of an ever-growing list of ways that advisors can provide value for clients. It’s a list that has grown so large that advisors can’t possibly do everything on it, and therefore need to choose which menu to focus on to best serve their own clients. In other words, for advisors who do plan to take an active role in clients’ credit management, Sora has the potential to be a significant value-add. However, it remains to be seen whether Sora’s solution is enough to convince advisors who weren’t planning on providing credit management to start doing so (particularly when it isn’t already something they’re paid to do), and whether there are enough advisors who do advise on client debts (or are willing to begin doing so) to build a substantive business for Sora.

In fact, since the launch of Envestnet’s Credit Exchange in 2019, it’s not clear whether “liabilities under management” has gained any material momentum with advisors. Clearly the majority of the industry is still focused on gathering assets, since (for AUM advisors at least) that’s the side of the balance sheet on which they hinge their own fees. With interest rates having risen sharply in the last year (and being still predicted to rise at least modestly above their current levels), the awkward reality is that advisors who start offering credit management today might find few opportunities for real savings on client’s existing debt, as the biggest opportunities lie in refinancing at lower rates (which is happening far more rarely now that rates are rising). Still, though, given how rates have historically risen and fallen with changing economic conditions, a return to normal conditions of bigger and/or more frequent changes (at least compared to the mostly rock-bottom rates of the 2010s) could create more opportunities for advisors to provide value by providing liabilities under management services as rates move up and down over time. This means both periodic refinancing opportunities and helping clients shop for the best loan terms at the exact time they need to borrow. Still, time will tell whether those conditions, coupled with evolving advisor business models, will translate into greater traction for the liabilities-under-management advice model.

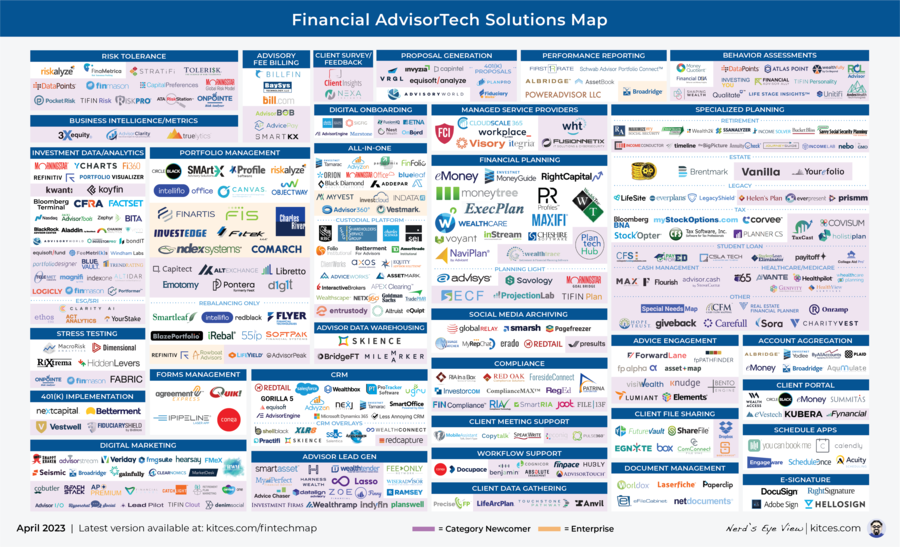

In the meantime, we’ve rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map with several new companies, including highlights of the Category Newcomers in each area to highlight new fintech innovation.

So what do you think? Is the combination of Altruist and SSG a viable competitor to the Big 3 RIA custodians? Would an end-to-end advice engagement tool like Lumiant’s be worth deploying in addition to — or even instead of — traditional financial planning software? Do credit management tools like Sora Finance’s make it worth offering liabilities under management as a value-add for clients?

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter @MichaelKitces.

Ben Henry-Moreland is senior financial planning nerd at Kitces.com, where he researches and writes for the Nerd’s Eye View blog. In addition to his work at Kitces.com, Ben serves clients at his RIA firm, Freelance Financial Planning.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound