The June edition of the latest in financial #AdvisorTech kicks off with the news that Riskalyze has completed its previously announced rebranding, and will now be known as Nitrogen, a “growth platform” for advisory firms. This represents less of a shift in the platform’s core function given that Riskalyze’s risk tolerance tool was always more about providing a clear way for advisors to generate a proposal that demonstrates their value to prospective clients and facilitates their conversion into paid customers than it was about quantifying risk tolerance for compliance purposes. Instead, the rebranding represents more of an acknowledgment of the firm’s true value proposition as a sales enablement tool that has allowed it to achieve dominant market share despite spawning numerous low-cost risk tolerance assessment competitors.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting advisor technology announcements, including:

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month’s column, and a discussion of more trends in advisor technology, including:

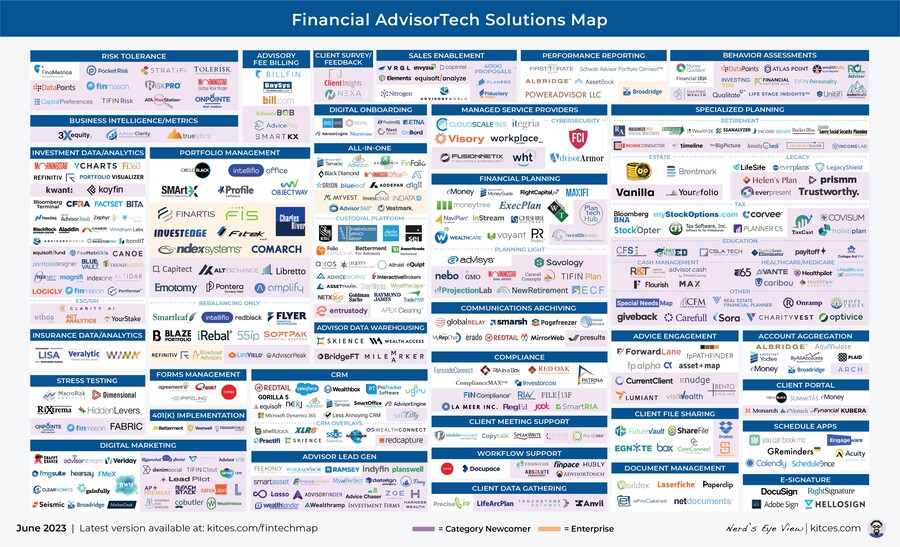

Be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map and also added the changes to our AdvisorTech Directory.

AdvisorTech companies that want to submit tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to TechNews@kitces.com.

In the early days of the financial planning field, the majority of the financial planning that advisors did for clients occurred before they actually became clients. Financial plans were effectively sales tools that highlighted gaps between the client’s current reality and their intended goals that the prospective client could help bridge by implementing the mutual funds or insurance products the advisor was selling, or later, the investment portfolios that the advisor would manage for the client.

As financial planning became less product-centric and more advice-centric, however, financial plans and financial planning increasingly became not a tool used to make a sale or secure a portfolio management agreement, but instead the product itself, for which the client paid a separate planning fee. This meant that, on one hand, financial planning software evolved to go even deeper to provide a unique analysis of the client’s situation and craft more individualized and sophisticated recommendations. On the other hand, since financial planning was now on the other side of the sales process (i.e., was delivered to validate the planning fee after the client signed on for the engagement), advisors now needed some other way to show their value to prospective clients. Specifically, ones who had already found the advisor, through their website or other marketing channels, and wanted a more hands-on demonstration of how the advisor could specifically help them invest their portfolio to reach their goals.

Against this backdrop, Riskalyze launched in 2011. While it was branded as a risk tolerance tool — and differentiated itself as an alternative to traditional compliance-mandated questionnaires with an attractive visual experience and an easily-digestible risk number score — in reality Riskalyze really functioned as a sales enablement tool. It filled the void left behind when comprehensive financial planning software largely left the sales realm. It did this by using prospective clients’ risk tolerance as a means to generate proposals that showed a gap between the excess risk of the client’s existing portfolio and the advisor’s alternative that was better aligned to the client’s tolerance. As a result, even though Riskalyze spawned a number of lower-priced risk tolerance competitors, it continued to gain dominant market share by solving the need not for yet another risk tolerance tool, but for proposal generation and other sales enablement needs for advisors.

Riskalyze CEO Aaron Klein acknowledged the reality of Riskalyze’s role in the advisory tech stack in the fall of 2022 when he announced that the company would rebrand in 2023 as a “growth platform” for advisors, rather than just a risk tolerance assessment solution. In May, Riskalyze officially rolled out its rebranded growth platform, as well as its new name, Nitrogen, a word that draws natural connections to growth — which depending on your perspective could be slow and organic (as in nitrogen fertilizer) or explosive (as in nitrous oxide rocket propellant).

From an advisor’s perspective, the rebrand primarily serves to make it clear exactly what Riskalyze/Nitrogen is for. To that end, it helps clarify the platform’s value proposition: Advisors seeking a risk tolerance tool primarily for the purposes of checking off compliance requirements around investment suitability may have balked at Riskalyze’s price point, which now runs at $395 per user per month, whereas paying that amount for a sales tool in Nitrogen that is tied directly to bringing in new client revenue might seem more reasonable. Going forward, it’s fair to expect that Nitrogen’s product updates will go beyond enhancements to the core risk tolerance tool and branch into other areas of facilitating sales. Perhaps, it might venture into areas of advice engagement as well since growth can come not just in the form of bringing on new clients, but in providing deeper value to — and getting commensurately higher fees from — existing clients, as Riskalyze expands on capabilities like its “Client Check-Ins.”

Ultimately, though, the Riskalyze/Nitrogen rebrand serves to highlight the opportunity that exists for platforms that can provide solutions for sales enablement, i.e., tools that can help facilitate sales to prospective clients. This is distinct from pure marketing in that it focuses on prospective clients who have already found the advisor and are going through the bottom-of-funnel sales process, not on bringing top-of-funnel leads to the advisor to begin with. Outside of a handful of proposal generation tools like CapIntel, VRGL and AdvisoryWorld, there are few platforms that focus primarily on the space between when a prospective client contacts an advisor and when they actually sign on as a client. In light of the Nitrogen launch, we’ll be reorganizing our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map to include a new sales enablement category, initially consisting of Nitrogen, plus the solutions in the existing proposal generation category, to highlight what could become a growing category in future years.

At the same time, though, the solutions that do exist in the emerging sales enablement category — including Nitrogen — are currently focused primarily on converting new prospects from a portfolio management perspective. This leaves the question of what future competitors will enter the sales enablement marketplace with more financial planning-centric tools echoing the OG financial planning software that initially occupied that territory.

In the late 1990s, when the internet and low-cost broker-dealers created platforms allowing consumers to buy mutual funds and other investments directly rather than having to get them through a financial advisor, as was previously required, it became clear that advisors of the future would need to build portfolios for clients differently than they had in the past. Whereas once the approach was centered around buying a collection of mutual funds, with each fund evaluated on its own individual merits, it increasingly became more about creating a single holistic portfolio designed around the client’s risk tolerance and investment horizon.

But once such diversified, asset-allocated portfolios became the norm, it became clear that a portfolio that worked for one client would also work for any other client with a similar risk tolerance or time horizon. This ultimately led to the emergence of turnkey asset management platforms, or TAMPs, and their sister offerings, separately managed accounts, or SMAs. Rather than build bespoke portfolios for each individual client, advisors could help clients select the right model portfolio to fit their needs and goals, but outsource the portfolio design and even trading itself to a more centralized platform (e.g., third-party managers who designed and then implemented portfolios on behalf of advisors and clients). This made it more efficient to deliver more in-depth portfolio management at scale.

In this environment, Envestnet emerged as early leader, successfully weaving together a platform that brought together a marketplace of third-party TAMP and SMA managers (who wanted to gather assets), with a cohort of advisors (both independent RIAs and, especially, tens of thousands of advisors on independent broker-dealer platforms who were searching for ways to scale portfolio management). It would then build (or more often, acquire) the technology to provide an ever-more-holistic advisor technology solution that would tie advisors into its manager marketplace. The success of Envestnet’s model was so pronounced, in fact, that in the 2010s it spawned a number of competitors who wanted to vie with Envestnet for the lucrative business of distributing third-party asset managers. They tried to execute a version of the Envestnet playbook of acquiring various solutions (e.g., portfolio accounting and performance reporting, financial planning software, CRM, etc.) and bringing them all together in the hopes that an Envestnet-style holistic advisor platform would allow them to win away Envestnet’s advisors (and enterprise clients that aggregated those advisors).

One notable challenger to Envestnet was InvestCloud, which had its own fairly meteoric rise in platform assets as it acquired its way to volume and scale. Founded in 2010, in a short stretch InvestCloud acquired Advicent (and its financial planning platform NaviPlan) to power its financial planning solution. InvestCloud completed a recapitalization that included acquisitions of fund distribution platform Tegra118 and private banking platform Finantix. Promising an “international financial supermarket” to connect asset managers with financial advisors, InvestCloud actually surpassed Envestnet in its self-proclaimed assets under administration (i.e., the total assets of clients across its platform), accumulating over $6 trillion largely as a result of its growth-by-acquisition strategy.

From outward numbers, then, InvestCloud appeared to be a successful until the news broke in April of a major leadership shakeup at the company, which saw an exodus of the bulk of the leadership that has been building InvestCloud as an Envestnet competitor over the last 10 years. First, there were CEO John Wise, chief corporate development officer J.P. Whelan and president of sales operations and integration Fiona Francis. Then, four days later, they were followed by chief product officer of digital wealth Yaela Shamberg, executive vice president of business development Michael Smith, chief information officer Vincent Sos Muñoz and president Colin Close. Even though InvestCloud has not said outwardly that there’s anything wrong, it’s hard to see this level of executive leadership turnover (whether by their own choice, in a purge led by InvestCloud’s private equity owners, or some combination thereof) as anything but a negative referendum on how successfully InvestCloud is actually competing with Envestnet for business.

InvestCloud’s shakeup highlights two core issues with emulating Envestnet’s success in the platform-TAMP marketplace. First, in the financial services industry — where client and advisor turnover is so low, and platforms rarely change their own core technology more than once every decade or so — it’s not enough for software providers to simply build (or buy) their way to a competitive tech platform; enterprise relationships and distribution capabilities matter. InvestCloud appears to be one in a long list of Envestnet competitors that have underestimated how effective Envestnet has been in the ground game of distribution and relationship management, particularly in the independent broker-dealer marketplace.

Second, acquiring multiple advisor technologies to band together in a manner that actually works better as a whole than the sum of its parts is radically more difficult than most companies seem to predict. That’s embodied not only by InvestCloud’s struggles in cobbling together an integrated platform to successfully take on Envestnet, but also by Tifin (which is reporting layoffs while struggling to entice assets away from Envestnet), as well as Envestnet’s own activist shareholder woes (with investors complaining it has not achieved enough growth development on its acquisition and integration strategy over the last 10 years).

This continues to highlight how hard it is to execute both distribution and enterprise relationships, and build a truly holistic platform where the parts actually integrate together in a meaningful way when the parts come together by acquisition. In an ultra-competitive environment for investment management technology, the stakes are clearly high enough that a disappointing return on that outlay was sufficient grounds for InvestCloud’s owners to reset with a new leadership team. Or as Ryan W. Neal succinctly quoted out in his analysis of the story, “If you come at the king, you best not miss.”

As a financial advisor, it’s great to have a lot of technology that you can use but it’s not so great to have a lot of technology to use. Advisors have an incredible number of different technology tools available to help them with almost every aspect of their job. However, the increasingly evident paradox is that the more different software solutions that an advisor uses each day to streamline their work, the more of a chore it is just to manage it all, from keeping track of logins and two-factor authentication across so many different applications, to onboarding and training and getting the most out of each tool, to evaluating new tools and the ever-growing list of features rolled out by existing software each month.

Complicating matters is the fact that while some software can fully complete some task that would otherwise take up a meaningful amount of the advisor’s time (e.g., meeting scheduling software like Calendly that eliminates the need for an email back-and-forth to confirm schedules and send a calendar invite), other tools really only provide the means to facilitate some broader function (like rebalancing software, which can calculate and execute rebalancing trades but still requires the advisor to create model portfolios, get compliance signoff and assign clients to appropriate models). This is especially true in the domain of marketing technology. On one hand, technology can streamline some parts of the marketing process (e.g., website development, email marketing automation and social media management), but at the end of the day, the technology really just aids a broader marketing strategy that’s still on the advisor’s shoulders to envision, design and execute, unless they decide to outsource their marketing to a third party.

To this end, outsourcing is on the rise among advisory firms, driven by two key factors: The growth of advisory firms in general, with the ongoing accumulation of clients inevitably meaning that firms have more work on their plate than the advisor themselves has the capacity to handle; and the rise of virtual and remote work, which has fueled the growth of centralized outsourcing platforms offering fractional services which provide the exact amount of service the firm needs (at a commensurate fractional price) in areas like virtual admin support, paraplanning and various forms of done-for-you outsourced marketing.

In this vein, digital advisory marketing platform Snappy Kraken has announced the launch of Freedom360, a service that takes Snappy Kraken’s core technology around marketing automation and, instead of leaving advisors to implement the tech, allows them to pay Snappy Kraken to do it on their behalf. In other words, Freedom360 gives advisors freedom from the burden of still being responsible for using the technology that Snappy Kraken sells.

From the advisor perspective, Freedom360 is akin to eMoney’s piloting of an outsourced paraplanner solution several years ago, which raised questions at the time about how some software meant to streamline complex tasks can be itself so complex that it can make sense to hire a person just to use the software who knows how to best leverage its value and how that person may as well be someone who works for the technology company (since they’re the ones who build and sell it and presumably would know it best. Although the $750 per month price of Freedom360 is substantially higher than Snappy Kraken’s marketing automation technology on its own (which ranges from $99 to $409 a month), that’s not really the choice for advisors looking to fully outsource their marketing support. It’s between Freedom360, and hiring a full- or part-time marketing employee or agency, either of which would likely cost substantially more than the $9,000 a year that Freedom360 costs.

Ultimately, this raises an interesting question for companies like Snappy Kraken: When do they stop being an AdvisorTech provider and start being a service provider with its own proprietary technology platform that allows for more efficiency and less cost than a full-service agency? And for new startups in areas of AdvisorTech like financial planning, advice engagement and even business intelligence, one wonders whether it might even be a better strategy to build themselves in the direction of being a service company first and a tech company second. As Freedom360 demonstrates, advisors might pay seven times or more for technology plus the support of someone with the wherewithal to use it to its full potential, than they would for the technology itself. Stated more simply, a lot of companies might build a significantly larger business, and grow revenue faster, by building not just a tech-only business, but a service platform using proprietary technology.

In the long run, arguably there will ultimately be room for both approaches. Like the ongoing debate over whether it’s better to use an all-in-one platform with a whole suite of technology solutions in one package, or to buy individual best-of-breed solutions in each category, some advisors would rather put all the pieces together the way they want, while others would rather just have it work out of the box. The same applies to the emerging question of software-as-a-service versus software-and-the-service. Some advisors will inevitably want to retain full control over their processes (from marketing to financial planning and elsewhere), while others will gladly outsource responsibilities they don’t really want or need to execute in-house (especially when it can be done on a fractional basis at the level they need it). Given the industry’s history of building tech for tech’s sake, however, few companies have yet tested the software-and-the-service model, and Snappy Kraken’s move puts it at the forefront of an emerging trend of companies that not only build tech for advisors but can also operate as tech-enabled service providers.

It takes a certain amount of revenue to get a software company off the ground. Even as a relatively lean startup, there’s at least a developer building software, an onboarding/customer support employee, a marketing and sales employee, and a founder who presumably would like to be paid as well. After the employees’ salaries, there are costs of benefits and other overhead expenses like office space and technology, and it doesn’t take long to get to $500,000 or more in annual expenses for a software startup, which creates pressure on the company to get to a break-even level of cash flow as soon as possible.

The challenge for AdvisorTech startups specifically is that there are only so many advisors to sell to — numbering in the hundreds of thousands, as opposed to the tens or hundreds of millions of potential customers for technology sold to the general public. In practice, a significant portion of those advisors are tied to enterprise firms or broker-dealers, meaning they can’t just go out and buy their own software. Instead, they’re restricted to whatever technology is available, or required, via their enterprise platform, which further limits the immediately serviceable market for new advisor software providers (who generally can’t break in with the enterprise platforms out of the gate).

So when an AdvisorTech software company launches, a realistic number of initial customers might be around 1,000 advisors. Doing the simple math, the provider would need to price their software a little over $40 per month to get to $500,000 in annual revenue in order to break even ($40 a month times 1,000 users times 12 months equals $480,000). This is why so many software products in the AdvisorTech landscape — regardless of their type or category or feature set — typically start out charging around $40 to $50 a month per advisor. If the prospective user base may be smaller, such as for specialty planning software around niche topics, the monthly cost would need to be higher (e.g., $80 to $100 a month for 500 potential niche advisors) to achieve breakeven. That is, unless the company can find investors willing to provide capital to subsidize losses until there are enough users to turn a profit. Or the company can find an acquisition partner with enough scale to operate sustainably while charging a lower price for the software.

In this context, it’s notable that Lumiant — an increasingly all-in-one platform for financial advice and client engagement that was founded in Australia and launched in the U.S. last summer — has acquired Genivity, which makes a specialized planning software tool called the Health And Longevity Optimizer, or HALO. The acquisition was presumably made possible, at least in part, by the $3.5 million in seed funding that Lumiant raised earlier this year.

From the companies’ perspective, the acquisition makes sense. HALO fits in alongside Lumiant’s existing suite of tools, which seek to facilitate more conversations between advisors and clients that go beyond money and explore the client’s values, goals and well-being with the aim of building a plan for the client’s whole best life. Genivity adds another dimension to this approach with its HALO tool, which crunches data on factors like a client’s health, lifestyle and family genetic history to create a personalized longevity model that in turn can aid in projecting everything from lifespan to the likely number of active years in retirement, to anticipated health and long-term care costs through that individualized time horizon (and based on an individualized projection of potential health issues). Although HALO didn’t have significant market adoption — it didn’t have enough users to crack the most recent Kitces Research on AdvisorTech or T3/Inside Information Technology Survey — its presence on Lumiant’s platform (where it is as of now still being offered as a stand-alone product) may garner higher visibility among advisors who (being on Lumiant’s platform to begin with) are presumably predisposed to being open to the kinds of conversations around health and wellness that HALO seeks to foster.

But at a broader level, the acquisition raises more questions about just how many individual specialized planning tools can really exist on the market at one time. For advisors, specialized tools can help with going deeper into planning and providing more valuable advice. This can easily justify the cost of the tool when the additional capabilities lead to more clients added or retained by the advisor, or allow them to charge higher advisory fees for a deeper value proposition. However, there are only so many additional stand-alone tools that any advisor can add at $50 to $100 per month each. While some specialized tools (e.g., Holistiplan) might be an easier sell for advisors when they fall within the wheelhouse of the types of conversations that advisors typically have already with clients (tax planning is already part of the core CFP curriculum), software like HALO that is geared toward conversations around health care and longevity that advisors aren’t as comfortable with have a harder row to hoe when it comes to convincing advisors to justify yet another monthly software subscription.

And so, as interest rates rise and venture/PE funding tightens, it remains to be seen whether a trend will emerge of specialty software providers being acquired by larger platforms to integrate as an additional feature (or as an adjacent value-add for asset managers or advisor platforms trying to deepen their relationship with advisors, as was the case for T. Rowe Price’s recent acquisition of Income Solver and SSAnalyzer). While HALO and similar tools do have value in facilitating different types of financial planning conversations, it might be more attractive from an advisor’s perspective if it’s offered as an option alongside other tools that the advisor already uses as part of a single platform, rather than being forced to buy each on its own. It might also bring down the total cost for a series of such tools compared to the $50 to $100 that each would likely need to charge to support themselves on their own. While as Kitces Research has shown, advisors’ adoption of specialty planning tools has grown significantly in recent years, it’s increasingly clear that advisors can’t adopt all the tools at once. This leaves the marketplace to sort out which ones have enough demand to remain stand-alone tools, and which need to seek other M&A options to stay viable.

In the early days of software, companies made a software product, and users bought the product. To the extent that the company released a new version of the software in the future, that upgraded/new version might then be sold as a subsequent product. To a large extent, this pricing model existed simply because it was the only way to distribute software in the first place, as in practice, users effectively bought the floppy disk that held the software to be installed. It wasn’t until the advent of the internet, where software increasingly was hosted in the cloud and could be updated once, centrally, for all users, that it even became possible to sell software as a service, or SaaS, for an ongoing fee.

In the process of making this shift from local software installation to cloud-hosted software, the pricing model typically reflected the storage or overhead costs that the provider themselves faced. For instance, software that required robust servers to run was priced based on the number of servers the buyer needed. Alternatively, if data were housed in a centralized database, firms were charged by the database. It was only years later that SaaS companies increasingly migrated toward a value-based pricing model that recognized that if each user is gaining value from the service, the company can charge an ongoing software fee per user instead.

Because of this evolution, though, it’s not uncommon for a crowded marketplace to have some competitors still on an old pricing model (e.g., by database), while others are on a newer pricing model (per user). In categories like CRM that have multiple established competitors with different pricing models, this works out well for advisors. They can follow the pricing model that fits best for their firm. For example, solo advisors will naturally gravitate toward vendors that charge a per-user fee rather than pay for a per-database license that supports more users than they need, while multiperson firms will seek vendors that sell a single-firm database license, which generally results in a lower per-user cost across multiple advisors at the firm.

But the flip side of this scenario is that for vendors, there’s an adverse selection effect at play. Since firms will tend to seek the vendor that provides the best pricing, each vendor will end up serving the types of firms that are least profitable for them. Those that charge per user will need to spend a lot of money and effort on attracting and retaining users since many of those users are solo firm owners with the power to stay with, or leave, the vendor. Those that charge for multiple users will require a lot of outlay on onboarding and ongoing service since they’re getting paid the same whether there is one user or 10 on the license.

Software providers have handled this challenge in different ways. For example, portfolio management tools usually require a minimum fee per firm (historically in the range of $10,000 to $15,000 per firm) to cover the cost of sales, onboarding and legacy data conversion, regardless of the underlying pricing model — and being so close to advisors’ revenue centers, advisors were willing to pay. But in the CRM space, the data show that advisors have generally followed the pricing model that works best for them. For instance, Kitces AdvisorTech Research shows that Wealthbox, with its per-user fee, has increasingly dominated in the small advisory firm marketplace, where it undercuts the competitors. Redtail — which still operates on a per-database fee for each firm covering up to 15 users, is the top choice for midsize firms with multiple users. Salesforce, the third-largest competitor, gets more traction in the larger enterprise marketplace with its customizability and deeper capabilities for firms with 10 or more advisors.

If you were a software provider like Redtail that charged a single fee for every 15 users, and consequently had many 10- to 15-person firms sign up to take advantage of that pricing, you might be tempted to switch to a per-user fee that immediately turned every user on your platform into a paying customer. In fact, that’s exactly what Redtail has announced that it’ll be doing. As of June 9, both new and existing users will be converted from their previous pricing structure of $99 for up to 15 users to one of two new pricing tiers, both charged per user: $45 a month for the basic Launch tier (which is only available for firms with up to five users), and $65 a month for the Growth tier (which also includes access to Redtail Imaging document management, the Redtail Speak compliant texting platform, and an expanded list of advisor tech tools from Redtail’s parent company Orion).

From Redtail’s perspective, the change makes Redtail more competitive for solo and startup advisory firm business with the likes of Wealthbox, which charges $49 a month and $65 a month for its respective Basic and Pro tiers (and had been undercutting Redtail’s $99 per month-for-at-least-one-database minimum). This makes sense for them, given that firms tend to change their CRM provider so rarely that winning their business at the outset can likely mean keeping them as a customer for a decade or more. However, the change is arguably far more financially impactful for Redtail with its core of midsize advisory firms, since a firm with 10 users that paid $99 a month for Redtail under the old model will see their cost jump to $650 per month overnight. However, it’s worth noting that even under its new structure, Redtail merely makes itself competitive with others like Wealthbox and Advyzon (that are around its price point), and is still significantly less costly than Salesforce, whose heavy customization capabilities come with a cost that is often north of $125 per user (which typically limits it to enterprise users that have such a need for Salesforce’s additional capabilities that they’re willing to pay up for it).

In fact, the irony is that from Redtail’s perspective, it was arguably so underpriced with its old pricing tier that it could lose half of its existing midsize firms and still double its revenue — with the sheer size of the price increase indicating that Redtail leadership has done the math and accepted that a significant number of Redtail firms are at least going to consider its competitors, if not leave outright. Redtail’s competitors may also well see a growth boom of midsize firms that now for the first time may be willing to consider competitors whose pricing is suddenly no longer much higher but merely in line with Redtail’s own cost, allowing them to get a foot in the door to compete on their features and value.

Or stated differently, Redtail’s pricing change has effectively made the entire addressable market in CRM software significantly larger in revenue terms. Ironically, this means that it will likely be a boon to almost all CRM systems – including Redtail itself (which will reap the benefits from rightsizing its price in the mid-tier advisory firm market), as well as competitors that have the opportunity to win market share away from Redtail now that they are similarly priced, with the obvious caveat that the fee increases in the aggregate will come at the expense of advisory firms themselves. Yet with CRM as the highest-adopted category of AdvisorTech software, which increasingly lives as the hub of an advisory firm’s entire practice, it seems likely that advisory firms will have little choice but to simply accept the higher cost of doing business.

The first generation of financial planning software was a relatively simple projection calculator. The tools took the inputs of what clients were currently saving and planned to spend in retirement, added assumed rates of investment growth and expense inflation, and solved for whether or not there were enough dollars to make it to the end. The upside to this was that it provided a straightforward framework to determine whether the client was likely to have enough money to last through retirement. The major downside, however, was that it didn’t account for sequence-of-return risk, which we now know has an outsized effect on the sustainability of retirement withdrawals, regardless of whether returns average out over the entire retirement time horizon.

Subsequent generations of financial planning software began to incorporate Monte Carlo analysis, which accounted for sequence-of-return risk by modeling 1,000-plus iterative scenarios while randomizing rates of return around probabilistic return distributions. The end result was a wide range of possible retirement paths, quantified in the form of a single probability-of-success number showing the percentage of instances in which the client had enough money to make it to the end. For advisors, the advent of Monte Carlo represented a great leap forward in the ability to quantify the risks that can imperil a client’s retirement (and perhaps provided some plausible deniability in that, if the advisor’s recommendations didn’t work out as hoped, the advisor had in fact shown a less-than-100% probability of success).

But despite the improvement over straight-line calculations, Monte Carlo still has its shortcomings. Most notably, it typically assumes that clients will make no adjustments to their current course over the life of the plan, such as spending adjustments or panic selling of risk assets in the face of steep market declines. This means that the probability-of-success number produced in most simulations has almost no bearing to the client’s actual chances of a successful retirement (given that in many cases the client has hired the advisor precisely to help them make the kinds of adjustments — and avoid the bad decisions — that will serve to improve their odds along the way). Additionally, Monte Carlo tends to suffer from an abstraction problem: Whereas most clients simply want to know whether they’re on track (which traditional straight-line projections were well able to provide a simple yes/no answer for), Monte Carlo produces a probability, which humans are notoriously bad at contextualizing and converting into a rational decision.

In this context, it’s notable that retirement income software provider Income Lab, whose advisory team includes Kitces lead researcher Derek Tharp, has rolled out a new retirement income stress-testing tool. Like Income Lab’s other tools, the Retirement Stress Test does away with the probability of success/failure framing, and instead focuses on adjustments that retirees can make to stay within risk-based income guardrails. Except in this instance, rather than using forward-looking assumptions for investment and inflation returns, it uses real-world historical scenarios (like the Great Depression, 1970s stagflation and the 2008 global financial crisis) to illustrate the adjustments that would have been necessary to stay on track during some of the worst-case periods in history.

In this sense, Income Lab’s stress test is notably different from traditional Monte Carlo analysis. While Monte Carlo does in a sense project how a portfolio would fare during extreme market volatility (in fact, Monte Carlo has been shown to often overestimate the prevalence of extreme multiyear market declines), that particular individual scenario is typically never seen by the client, but is instead buried within the hundreds or thousands of other plan iterations run by the software to produce the single probability-of-success number. This leaves the client with no sense of the real impact any given scenario would have on their lives — e.g., whether the shortcoming is “take one fewer vacation per year” bad, “sell the vacation home” bad, or “get a job and move in with the kids” bad. This means that, counter to the stress test label, Income Lab’s tool really seems to be about providing peace of mind in providing a tangible illustration of the specific actions a client might have taken to get through a major financial crisis. This may not be completely instructive for dealing with future crises, which will inevitably be different from the ones that came previously, but can perhaps show just how minor some spending changes need to be even to get through a worst-case scenario.

The ultimate question, though, is whether Income Lab’s stress-testing approach will really gain traction as a viable alternative to the popularity of Monte Carlo analysis among financial advisors. On one hand, it provides arguably a better framework for productive client conversations around retirement planning since clients can generally relate better to real-life periods in history than they can to an abstract probability-of-success number. On the other hand, it moves even farther away from the simple yes/no answer to the “Am I on track to retire?” question, and unlike Monte Carlo it doesn’t provide a single number that clients can use to track their progress over time.

Like many startups, Income Lab will need to navigate the challenges of making a product compelling enough to win advisors with its alternative approach, without making it so compelling as to attract a lot of attention from larger financial and retirement planning platforms that might simply copycat the same approach with their own software. Although if Income Lab does generate significant enough interest in its tools for modeling retirement scenarios and income adjustments, the question may shift to whether it’s more viable to continue growing its user base by distributing its tools as a stand-alone company — or to license them to/via a larger financial planning software platform to accelerate its distribution instead.

In the meantime, we’ve rolled out a beta version of our new AdvisorTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdvisorTech Solutions Map produced in collaboration with Craig Iskowitz of Ezra Group.

So what do you think? Is there a need for more tools that can help convert prospects into clients, beyond Riskalyze/Nitrogen’s Risk Score? What kinds of software do you use that you would be willing to pay someone to use the software for you, a la Snappy Kraken’s Freedom360? Does Redtail’s pricing overhaul warrant current users switching to a new platform, or does it just bring it back in line with the competition?

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter @MichaelKitces.

Ben Henry-Moreland is senior financial planning nerd at Kitces.com, where he researches and writes for the Nerd’s Eye View blog. In addition to his work at Kitces.com, Ben serves clients at his RIA firm, Freelance Financial Planning.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound