UBS Group has become an investor favorite in recent years as a reliable beacon of profitability. For Chief Executive Ralph Hamers, such stability poses a challenge: how to fix something that isn’t visibly broken. Coming from ING Groep, the Dutch lender he’s credited with transforming, the Dutchman’s mission statement is to pull UBS into the digital age.

Last week, he made his long-awaited first move, buying robo-adviser Wealthfront for $1.4 billion in cash.

The deal gives UBS more than 470,000 additional U.S. clients, notably a younger crop that’s still accumulating wealth. It’s a departure for the Zurich-based bank, long accustomed to providing personalized services to the ultra rich. Hamers says the bank must embrace a broader base, even if it means pushing lower-margin, automated products that aren’t the hallmark of UBS’s personalized offerings.

“Let’s not wait for somebody to eat our lunch, let’s do it ourselves,” Hamers said in an interview this month, before the Wealthfront deal was announced. “Do you dare to cannibalize your own business? You have no choice.”

But long-term employees priding themselves on tailor-made services worry that automated advice might dilute a cherished brand. Investors say that moving into unfamiliar territory will probably require more costly acquisitions. And Hamers still has to prove that he can put his stamp on the Swiss institution. His first full year passed with mainly cosmetic fixes like collapsing hierarchies or revamping tech teams, and his first strategic update last year got a lukewarm reception from analysts and staff alike.

UBS is poised to lay out new financial targets and give more clarity on its strategy when the bank reports fourth-quarter earnings Tuesday. The Wealthfront deal is the clearest indication yet where Hamers, 55, wants to take UBS, both geographically and strategically. He’s pushing for a mixed model, in which advisers personally focus on the wealthiest and most lucrative clients, while algorithms cater to less affluent and demanding customers.

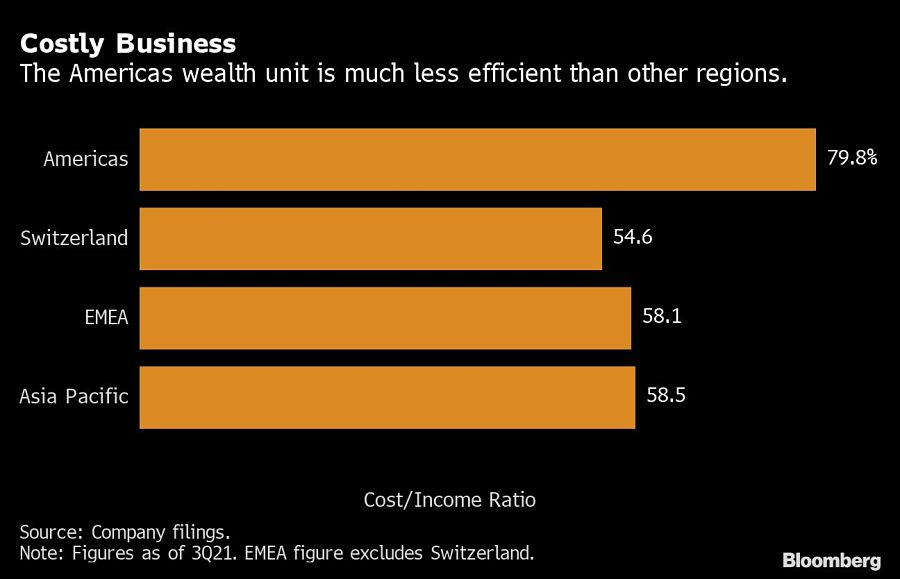

Stakeholders have long pointed to the bank’s U.S. operations as an area in need of attention. The business is too costly, with a cost-income ratio of 80% compared with less than 60% in all other regions. Assets are too sub-scale when stacked up against peers, and UBS lacks the investment banking punch to break into the Top 5 on Wall Street.

UBS remains committed to the region, because selling out the way Credit Suisse Group did in 2015 would effectively shut it out of the world’s largest wealth pool. Instead, Hamers sees the U.S. as a laboratory for his digital push, which will help cut costs. While some analysts questioned the relatively high price paid for Wealthfront, others expect the bank to pursue more bolt-on deals as it tilts more toward robo-advisers.

“The digital wealth offering is a model that will have to prove itself,” said Eric Hagemann, senior analyst at Pzena Investment Management, a UBS shareholder. “Can a human being in a call center deliver a credible substitute for a full-service high-touch model? It’s really unclear. And then that raises the question of is it really worth the cost of having human beings involved at all?”

Coming into a institution steeped in private banking tradition, Hamers — with his background in corporate and retail banking and direct Dutch approach — was initially viewed with skepticism by other leaders and their cohorts in UBS’s wealth arm. Financial advisers were concerned that he would replace centuries of practiced behavior with a flashy app that would alienate and ultimately drive away cherished clients.

It’s not the first time Hamers has sought to shake up a business that was doing well. But at ING, he had to reboot a strategy two years later, with stricter targets and thousands of job cuts, when internal resistance slowed down execution.

And the speed at which ING built out its digital platforms left the bank vulnerable to money laundering, resulting in a record fine in 2018 for shortcomings in its checks. Hamers himself remains the subject of a probe by Dutch prosecutors into his role in ING’s past failures to police money laundering.

Hamers concedes the wealthiest customers still need highly personalized advice that no machine could ever replicate. In theory, the digital-first model is more varied and flexible and comes with the added benefit of a human fallback should the client demand a more personal touch. It will push UBS into a lower category of wealth — those with $250,000 to $2 million in assets — that it hasn’t previously targeted in a meaningful way.

Pushing business through digital channels automatically chips away at margins. But UBS needs to act now while it has the funds to invest, Hamers said. Eventually, it could roll out the model in Europe and Asia, with some programs already being put in place this year.

“The reason it is so easy to disrupt in banking is that we don’t deal with physical goods,” Hamers said. “Music is digital. Money is digital. Everything that is an immaterial good can be disrupted through technology.”

It’s a message he’s taken great pains to get across. Hamers says the bank initially struck him as a hierarchical and divided when he first took over in late 2020. Units had few links to one another other than residing under the same roof, leaving the new CEO with a sense that he was running three separate banks, according to people familiar with his thinking.

An econometrician by training, Hamers has a keen eye for details and data, analyzing potential problems from every possible angle, according to people who have worked with him.

At UBS, his management style has also come across as unorthodox, the people say. If someone complains about a problem, he tells them to go fix it.

“People generally like to be told what to do,” Hamers said. “But my belief is, that most people know what to do.”

Hamers gave the executive team more oversight than just their own divisions. Rob Karofsky, the head of the investment bank, is now also co-head for the artificial intelligence data team together with digital head Mike Dargan, while the leader of asset management, Suni Harford, is also in charge of sustainability.

Hamers also abolished titles like group managing director, a crop of the most senior 100 or so employees across the bank. While they kept their elevated pay, they joined the ranks of ordinary managing directors. Mindful that his message might otherwise not filter through the sediments of management that remain, Hamers routinely appears in short, impromptu videos that he beams to all employees.

The CEO acknowledges that it will take time for his message to sink in. But at the same time, his patience isn’t endless because the disruptions are taking place now, and UBS can’t afford to sit them out.

“The shift to digital in wealth is literally happening now,” Hamers said. “Every client I have talked to over the last year and a half that I have been here says UBS has great products and the best advice, but oh man, you can really improve when it comes to digital.”

Executives from LPL Financial, Cresset Partners hired for key roles.

Geopolitical tension has been managed well by the markets.

December cut is still a possiblity.

Canada, China among nations to react to president-elect's comments.

For several years, Leech allegedly favored some clients in trade allocations, at the cost of others, amounting to $600 million, according to the Department of Justice.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound