In America’s richest enclaves, word spread quickly: A bank was offering loans on sweet terms.

Wealthy homebuyers and property investors with high incomes and sterling credit scores could get a mortgage from First Republic Bank with a rock-bottom rate for several years. Better yet, they didn’t have to start repaying the principal for a decade.

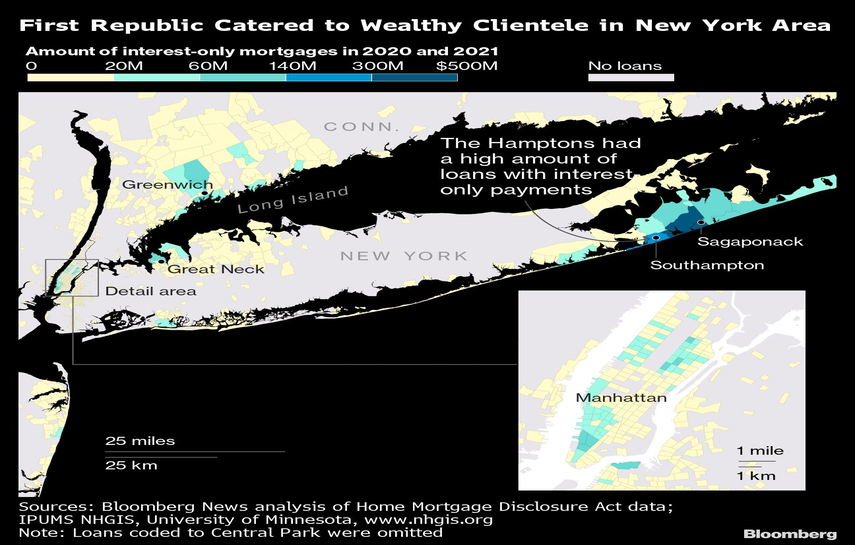

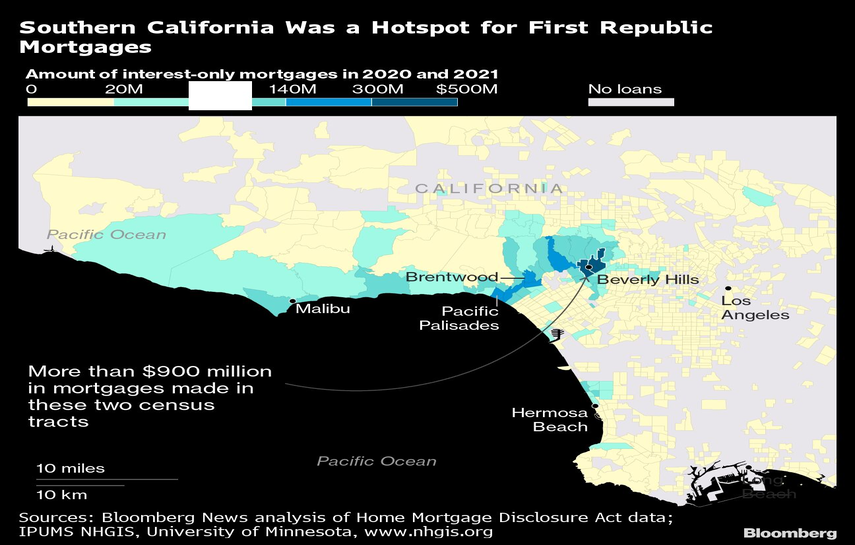

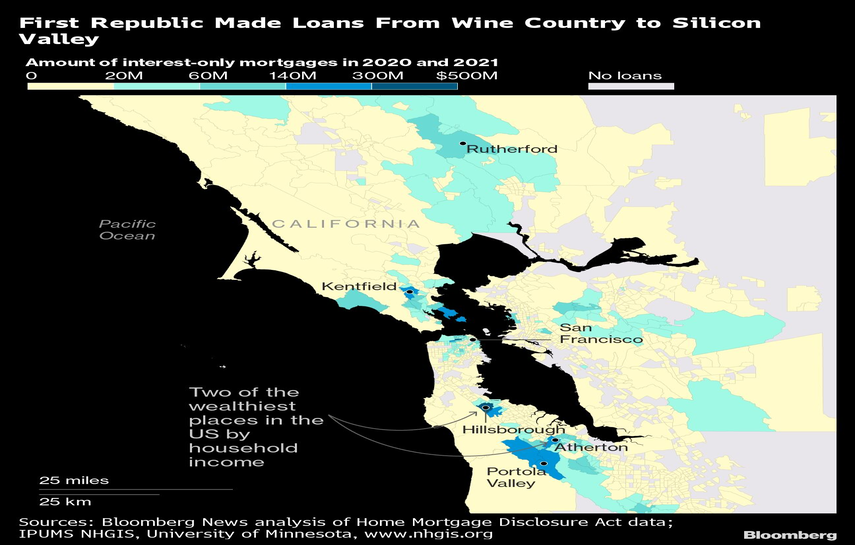

Across Manhattan, the San Francisco Bay area and Southern California, those terms attracted legions of wealthy clients — including executives from other banks — as interest rates sank during the pandemic. The loans left borrowers with more cash to invest and spend than if they financed their properties with more conventional mortgages. Demand was so strong that it helped First Republic double its assets in four years, while deposits surged.

Now, it's all looking like a colossal mistake.

The regional bank crisis has mostly focused on lenders' underwater bond holdings headed into a messy earnings season. Those contributed to the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Silvergate Capital Corp. last month after surges in withdrawals forced both firms to sell the securities at losses.

But at First Republic, which has lost almost 90% of its market value this year, such investments are only a piece of the issue. A much bigger challenge is its stockpile of low-interest loans, many of them to people who still have years to start paying them down. The mortgages are performing well, but their low rates and delayed repayments hurt their value.

The firm is set to report first-quarter results April 24 with analysts estimating it will post a $40 billion drop in deposits.

The loans have hampered efforts to find investors or a stronger lender to acquire the company, which is now leaning on $30 billion deposited by larger banks. The debt portfolio is one of the primary reasons several would-be rescuers aren’t willing to pony up cash, according to people with knowledge of their thinking, who asked not to be named discussing confidential deliberations.

The mortgages also make a government-backed deal all the more politically fraught: How eager will regulators or Wall Street’s critics in Congress be to aid a bank that hurt itself with a product tailored to rich clients?

While the loans complicate a classic takeover of First Republic by a more stable competitor, a deal isn’t impossible. One workaround would be to design a transaction that avoids a change in control of the bank, letting a rescuer avoid an upfront write-down, a person with knowledge of the situation said. Or First Republic could find a buyer so strongly capitalized that it could stomach the initial write-down, positioning itself for supercharged earnings as the loans are eventually repaid.

So far, no such deal has emerged.

Last month, First Republic’s predicament prompted Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to suggest an unusual industry-funded stopgap that led to JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp. and nine other US banks depositing $30 billion for at least 120 days. The move aimed to ensure the lender could keep operating smoothly while working on a solution. So long as it continues to have ample cash on hand, it can avoid costly asset sales, explore rescue deals, try persuading depositors to return or wait for debts on its books to regain their value or be repaid.

Until that happens, it’s unclear how those big banks can get their money out without upending the firm.

A spokesperson for First Republic declined to comment.

[Also read: Is first republic bank in trouble? First Republic’s cloudy future puts wealth management on notice]

The trouble with finding a buyer or new investors for First Republic comes down to simple math.

When rates rise, the market value of loans and other debt underwritten months or years before at lower interest levels generally falls. By the start of this year, First Republic estimated its $137 billion stockpile of mortgages would be worth about $19 billion less than their carrying value if sold off, its annual report shows. That compares to about $4.8 billion in unrealized losses on bonds the firm intends to hold to maturity and roughly $3 billion in markdowns on other loans on its books.

Altogether, that means that in a sale, First Republic could have to close a hole in its balance sheet that as of Dec. 31 stood at $27 billion. That’s about double the firm’s tangible common equity, a measure of capital that investors use to gauge a bank’s worth.

Even selling the bank at a price of $0 per share wouldn’t likely attract a buyer, David Chiaverini, an analyst at Wedbush Securities, wrote in a note to clients. “A would-be acquirer would essentially be paying $13 billion on top of whatever consideration is offered” to First Republic shareholders.

But it’s also hard to generate profits with so much low-interest lending weighing on the books. In mid-March, First Republic said it was paying around 5% for tens of billions of dollars in funding from the Federal Reserve and Federal Home Loan Bank. Mountains of mortgages and other loans it made to customers over the past half-decade generate less.

Among Wall Streeters, it was an open secret that the San Francisco-based lender was offering particularly attractive terms on mortgages. New York City property records from the past few years show customers came from all over the financial sector and included industry leaders such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc. President John Waldron, who took out an $11.2 million mortgage in June 2020, and R. Lawrence Roth, a board member at Oppenheimer Holdings Inc.

Another Goldman Sachs partner, a former executive at Blackstone Inc. and a managing director at private equity firm Sycamore Partners also borrowed millions from the bank, the property records show.

Beyond the finance industry, other examples of First Republic customers with seven-figure mortgages in New York include music mogul Todd Moscowitz, as well as an executive at a technology venture and the owner of a fine-art gallery, according to property records. All of their loans had 10-year interest-only periods and rates starting below 3%.

Roth, Waldron and Moscowitz declined to comment through company spokespeople.

Interest-only loans have been around for decades, with some banks offering them to select clients. The mortgages accounted for a tiny slice of the broader market as the millennium began, but by 2003 their popularity started to skyrocket as lenders pedaled them to less creditworthy customers, many of whom were speculating in hot housing markets.

Those loans were notorious by 2007, with a growing number of borrowers struggling to keep up with balloon payments or sell their homes. As the housing crisis escalated, interest-only lending plunged.

First Republic took a different approach, making interest-only loans to customers with ample wealth and strong credit histories a key part of its expansion over the past decade.

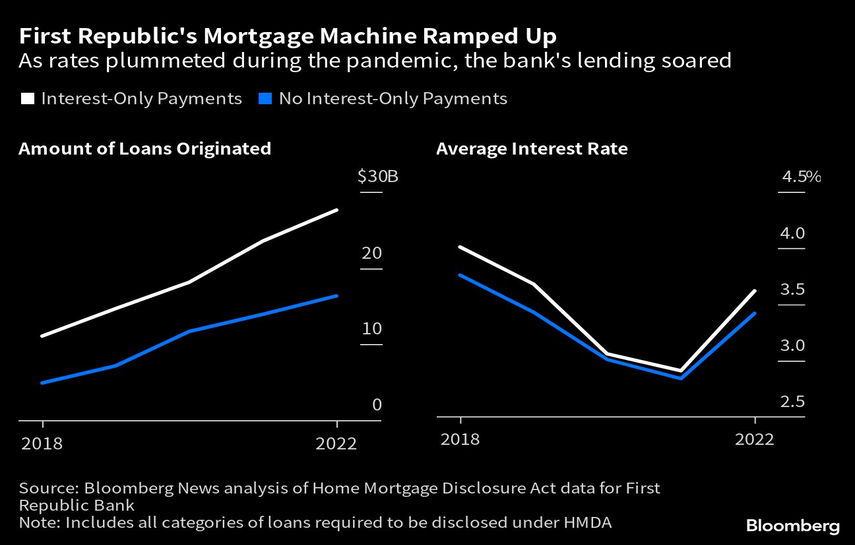

The firm’s annual reports show the business grew for years and then took off as interest rates bottomed out in 2020 and 2021. In that period, a Bloomberg News analysis of Home Mortgage Disclosure Act records shows that the bank made more than $19 billion in mortgages with interest-only payments in three metro areas alone: San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York. The debt also flowed in a big way to the Hamptons and the wine country north of San Francisco.

Last year, borrowers who opted for interest-only payments made $1 million a year on average, more than double the earnings of First Republic customers who opted for mortgages without that feature, the data show.

Interest-only mortgages made up a higher share of originations at First Republic than at any of its peers over the past half-decade, the analysis of HMDA data shows. By the start of this year, 59% of the bank’s loan book was comprised of single-family mortgages, and three-fifths of those — about $58 billion — were still in interest-only periods, according to the firm’s annual report. Principal payments on the vast majority don’t start until at least 2028.

Happy customers were a fixture in First Republic’s advertisements, with millionaires and business leaders extolling its customer service and dubbing the firm a “partner for life.” If homebuyers also parked cash at the bank, it could plow the money into other investments to burnish returns on those relationships. So many wealthy families, entrepreneurs and businesses deposited funds that surpassed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s $250,000 coverage limit, that some $119 billion — or two-thirds of the bank’s total deposits — were uninsured at the end of last year.

That unraveled when interest rates rose. In interviews, clients said they saw more opportunities to earn higher returns elsewhere. And when other banks with outsize piles of uninsured deposits started teetering this year, First Republic’s clients yanked their money, too.

Unlike the interest-only loans banks once made to speculators, First Republic’s mortgages have several hallmarks of safe bets. Over the past two years, its mortgage borrowers had a median credit score of 780 — well over the 720 mark that lenders typically use to define “super prime.”

That’s helped First Republic avoid credit losses. Since its founding in 1985, the bank has experienced only $45 million in cumulative net loan losses after originating $241 billion in single-family residential loans. By comparison, JPMorgan had $1.05 billion in charge-offs for consumer loans in the first quarter alone.

“Many of our borrowers have high liquidity and substantial net worth,” First Republic wrote in its annual report. “We have developed disciplined underwriting standards that have remained consistent through varying business cycles.”

Interest-only periods make it harder to keep track of borrowers who remain financially strong. Once loans are minted, banks typically can’t see how much those customers continue to earn. In recent months, San Francisco’s tech scene has been hit with layoffs by industry giants including Meta Platforms Inc.’s Facebook and Alphabet Inc.’s Google.

At the height of last month’s regional banking crisis, First Republic’s stock price plunged by more than 40% on several days, and as much as 79% inside a single session. Across the industry, executives worried that if the firm failed, more banks would come under pressure. That tumult began subsiding around March 25. US regulators keeping tabs on the firm concluded withdrawals were easing and it was stable enough to operate without an immediate intervention, Bloomberg reported that day. The stock steadied and has since climbed 6%.

Behind closed doors, authorities floated an unusual idea for helping the bank if the situation worsened again: expanding an emergency Federal Reserve facility in a way designed to bolster First Republic, people familiar with the talks said at the time.

The Fed’s facility currently accepts instruments including US Treasuries, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities. Any changes would have to apply to all banks, the people said, but officials believed it would be possible to widen the facility in a way that ensured First Republic would benefit.

It’s unclear what sort of assets or terms they had in mind. But the bank’s mortgage portfolio is unique.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound