Bill Gross has dumped all Treasuries from the world's biggest mutual fund, Warren Buffett is shifting to shorter-term debt, and Swiss Reinsurance Co. is boosting equities and corporate bonds.

Some of the biggest private investors in the bond market, from fund managers to insurers and pensions, are preparing for an end to the three-decade Treasury rally, as interest rates near zero and unprecedented spending by the U.S. government and the central bank threaten to fuel inflation. Their strategies range from reducing the longest-dated holdings and shifting to higher-yielding corporate debt, to investing in stocks, commodities, non-U.S. bonds and even holding cash.

“U.S. government bonds are not a safe haven,” Jim Rogers, the global investor who predicted the 2007-2009 housing-market crash, said in a telephone interview from Singapore. “I cannot conceive of lending money to the U.S. government for 30 years.”

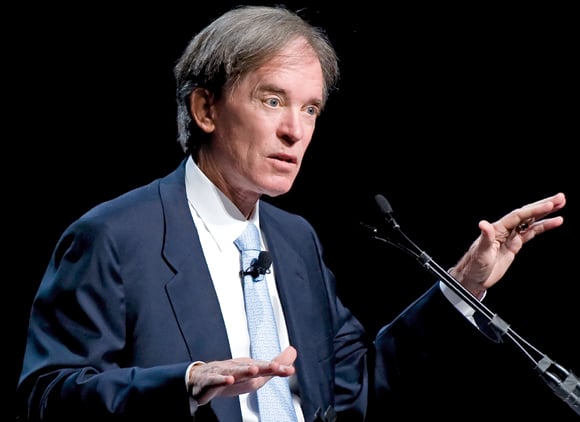

Pacific Investment Management Co. said yesterday that Gross, who runs the $237 billion Pimco Total Return Fund, eliminated government-related debt from his flagship fund last month as the U.S. projected record budget deficits. Gross, who has overseen the expansion of Pimco into a $1.2 trillion bond shop over four decades, predicted a year ago that “bonds have seen their best days.” Last month, he said Treasuries may have to be “exorcised” from model portfolios.

The bonds, considered the safest and most liquid, have been an investment staple for generations. The U.S. is the world's biggest debt issuer, with $14.2 trillion outstanding. Most of that is owned by U.S. government entities, foreign countries such as China and Japan, and investors including mutual funds, pension funds, insurers and banks.

Click here to participate in an InvestmentNews quick hit survey on inflation and clients' bond portfolios.

Real Assets

Mutual funds, which collectively represent the largest private owners of U.S. debt, cut their holdings by 17 percent to $638 billion as of June 30 from the end of 2008, according to federal government data. Treasuries have lost 0.3 percent this year, after returning an average of 8.8 percent a year since interest rates peaked in 1981, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch indexes.

Jeffrey Gundlach, who runs fixed-income specialist DoubleLine Capital LP in Los Angeles, said he's looking to real assets to lift returns. DoubleLine last month opened its first fund with the freedom to invest in a mix of assets including equities, real estate and commodities.

Gundlach, whose $5.3 billion DoubleLine Total Return Bond Fund has returned 19 percent since opening last April, had 93 percent of assets in mortgage bonds and none in Treasuries at year-end, Bloomberg data show.

‘Devilishly Difficult'

“Tactical investing is more important than ever before,” Gundlach, who has more than half of his personal wealth in real assets, said in a telephone interview. Government policies and rising commodity prices make it “devilishly difficult” for investors to profit in U.S. bonds, he said.

Pimco, based in Newport Beach, California, and led by Mohamed El-Erian, has opened a global stock fund and plans to start two that invest in the emerging markets. The firm has hired executives who previously worked at Franklin Resources Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., and this month added seven analysts and traders to help expand the active stock-fund unit.

Pimco Total Return in December expanded its mandate to invest as much as 10 percent of its assets in preferred stocks and convertible debt, a hybrid security that can be converted into stock at a predetermined price, according to a regulatory filing.

BlackRock ‘Underweight'

BlackRock Inc., the world's biggest money manager, has moved to shorter-duration securities because of the potential for interest-rate swings and is “underweight” Treasuries relative to benchmark indexes, Rick Rieder, chief investment officer of fundamental fixed income at the New York-based firm, wrote in a February investment commentary.

BlackRock started expanding beyond bonds a decade ago by making acquisitions, including the 2006 purchase of Merrill Lynch & Co.'s investment unit. The firm, formed in 1988 as a fixed-income manager, in 2009 bought Barclays Global Investors. Rieder, who co-manages the $3.4 billion BlackRock Total Return Fund, had more than half of its assets in mortgage-related securities as of Dec. 31, according to a quarterly report. About 26 percent was in Treasuries.

U.S. debt entered a bull market in the early 1980s, after Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker raised interest rates to as high as 20 percent to tame inflation. In the years that followed, inflation and interest rates declined, pushing up bond prices, which move inversely to yields. The 10-year Treasury yield, which reached a high of 15.8 percent in September 1981, fell to as low as 2.05 percent on Dec. 30, 2008.

‘Artificially Low'

That yield has risen to 3.47 percent as of yesterday. The Fed, after spending $1.7 trillion in the wake of the global financial crisis to end the recession, said in November it would buy an additional $600 billion of Treasuries through June to help the U.S. economy. The Fed and the Bank of Japan are alone among the major central banks in indicating they have no plans to increase rates.

Gross has said he may buy Treasuries again if yields rise. Laurence D. Fink, chief executive officer of BlackRock, said in an interview last week that he's a “big buyer” of the U.S. dollar and he doesn't see a “bear market” in bonds.

Bond buyers outside the U.S. have added longer-term debt, showing that some agree with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke's assessment that inflation will be contained even as global food and energy prices soar. China, the largest foreign investor in U.S. government debt, bought more U.S. bonds in December even as its leaders criticized Bernanke's plan for the Fed to buy $600 billion of Treasuries by June.

‘China's Faith'

“China has kept on lending money to the U.S. to keep its export machine going, and to prevent losses” on its existing holdings of Treasuries, said Yu Yongding, a former Chinese central bank adviser. “Perhaps it is too late to do anything about the existing stock without causing a serious political and financial backlash. But at least China should stop continuing building up its holdings.”

China's currency's de facto peg to the dollar limits its ability to diversify away from Treasuries even while its policy makers are “very, very bearish” on the dollar, said Andy Xie, formerly Morgan Stanley's chief Asia economist in Hong Kong. China's probably trying to diversify by increasing purchases of euro-denominated bonds and buying bonds with shorter maturities to minimize risk, Xie said.

“China's faith in the Fed broke a few years ago,” said Xie, now an independent economist based in Shanghai. “China used to be enamored of people like Greenspan and Bob Rubin even though at that time the dollar was coming down. QE2 destroyed whatever faith was left.”

‘Who Will Buy?'

Moves by the Fed to pump money into the economy are keeping interest rates “artificially low,” Gross wrote in a letter to investors published March 2. The central bank's purchases have resulted in 10 percent of publicly issued U.S. debt being owned by the Fed, 50 percent by foreign governments and 40 percent by private investors such as fund managers, insurance companies and banks, he said.

“The legitimate corollary question is: Who will buy Treasuries when the Fed doesn't?” Gross wrote.

Like Gross, Loomis Sayles & Co.'s Dan Fuss has expanded investments in non-U.S. bonds and equity-linked securities. The $19.9 billion Loomis Sayles Bond Fund has been reducing Treasuries for more than a year in favor of high-yield bonds, said Kathleen Gaffney, co-manager with Fuss. Junk bonds accounted for 24 percent of the fund's assets as of Jan. 31, while 11 percent was in convertible debt, according to the firm's website. About 2.4 percent was in U.S. Treasuries.

‘Excellent Liquidity'

“Treasuries are the one sector we would avoid, but the one positive about it that it provides investors with excellent liquidity,” said Gaffney, whose fund has beaten 96 percent of its peers in the past five years, according to Bloomberg data. “So we have plenty of government bonds with liquidity, just not in the U.S.”

The fund has shifted money into Canadian government bonds, Gaffney said in an interview. About 13 percent of the fund was in Canadian debt, according to the website.

Loomis Sayles, the Boston firm that oversees $152 billion, last year hired a portfolio manager and three research analysts from Evergreen Investments LLC as part of a plan to expand its stock-fund unit.

The impact of the Fed's efforts to stimulate the economy by buying Treasuries, questions over the durability of U.S. growth and rising oil prices spurred by unrest in the Middle East have created a “confusing landscape,” Cynthia Steer, managing director of investment strategy at Russell Investments in Seattle, said in a phone interview.

‘Wise Investors'

More institutional investors are seeking to break away from broadly used benchmarks for U.S. bonds, such as the BarCap U.S. Aggregate Total Return index, and use a combination of indexes that incorporate bonds all over the world, Russell's Steer said.

“Wise investors started diversifying away from the BarCap Aggregate index a decade ago into areas such as global bonds,” said Steer, whose firm manages $149 billion for institutional clients. “Alternatives such as hedge funds investing in credit should be part of the good investment program.”

Rogers, the chairman of Rogers Holdings who correctly predicted the start of the commodity rally in 1999, said he plans to sell Treasuries short, betting on a price decline, because of the “staggering” U.S. debt load. Net interest expense to service the national debt will triple to an all-time high of $554 billion in 2015 from $185 billion in 2010, according to the Obama administration's adjusted 2011 budget.

Buffett's Holdings

Rogers said he had a short position in U.S. Treasuries until the Middle East protests that began in Egypt in January prompted him to unwind the wager on expectations that demand for U.S. bonds would rise temporarily. He said he'll take a new bearish stand when prices climb.

Insurers, whose flexibility to allocate to different assets is limited by regulators, are buying bonds with shorter maturities to protect their investments from rising interest rates. Investors who buy longer-term securities face the risk that interest rates may spike, hurting them if they want to sell before the debt matures.

Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc. brought the percentage of securities maturing in a year or less to 23 percent as of year- end, according to a Feb. 28 regulatory filing. That compares with 16 percent when the Omaha, Nebraska-based company started disclosing the duration of investments 18 months earlier. The holdings include Treasuries, municipal debt, foreign-government securities and corporate bonds.

Swiss Re

Swiss Re, which trails only Munich Re by assets among reinsurers, is buying about $7 billion of “high-grade” corporate bonds to improve investment returns, Chief Financial Officer George Quinn said in a Feb. 17 interview from Zurich.

The company will also, depending on market conditions, increase stocks to 3 percent to 4 percent of its $149 billion investment portfolio by year-end, from 2 percent, Quinn said. The reinsurer last had that much in equities in the second quarter of 2008, according to quarterly statements.

Allstate Corp., the largest publicly traded U.S. home and auto insurer, is sacrificing yield for flexibility on the $49.9 billion in fixed-income holdings at its life-insurance division by acquiring shorter-duration bonds, according to Chief Executive Officer Thomas Wilson.

“We are staying short in Allstate Financial, so that when rates come up we can reinvest at higher rates and lock in good long-term returns,” Wilson, whose firm is based in Northbrook, Illinois, said in a Feb. 9 interview. “But that's costing us today in operating income.”

‘Hard Assets'

Liberty Mutual Holding Co. CEO Edmund “Ted” Kelly has decreased the percentage of fixed-income assets in the Boston- based insurer's $69.8 billion investment portfolio, while adding to equity and energy holdings.

“We have obviously long-term liabilities that will increase with inflation, so to protect ourselves we have been investing heavily in hard assets,” Kelly said in a Feb. 17 interview on Bloomberg Television's “Street Smart.” “We're a big holder of oil and gas, we're into mining and minerals and we just finished in wrapping up developing a wind farm in northeast Brazil.”

Pension funds, facing potential shortfalls in meeting their liabilities to retirees, are adjusting their allocations as well. Pensions surveyed by Greenwich Associates predicted fixed- income returns would decline to 4.8 percent annually over the next five years, from 5.7 percent predicted a year earlier, according to a Feb. 8 report by the Stamford, Connecticut, consulting firm.

Calpers' Target

California Public Employees' Retirement System, the nation's largest public pension plan at $230 billion in assets, in December cut its target allocation to bonds and raised the portion for assets that guard against inflation.

Calpers, as the Sacramento-based retirement fund is called, reduced its target for corporate bonds to 16 percent from 20 percent as part of a broader shift aimed at lifting returns. The pension added to inflation-linked securities and infrastructure to protect itself from the impact of possible price increases.

“We learned in the financial crisis and the past recession that a liquidity crunch or inflation can have a significant impact on portfolio performance in ways that many investors didn't anticipate,” Rob Feckner, president of Calpers's board, said in a Dec. 13 statement announcing the changes.

--Bloomberg News--