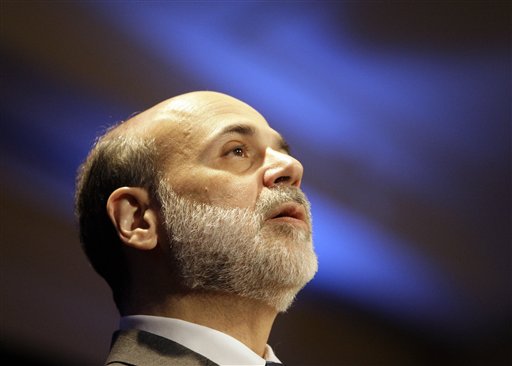

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke told Congress on Wednesday that record-low interest rates are still needed to ensure that the economic recovery will last.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke told Congress on Wednesday that record-low interest rates are still needed to ensure that the economic recovery will last and to help ease the sting of high unemployment.

In his twice-a-year report to the House Financial Services Committee, Bernanke struck a confident tone that the recovery should endure. But he also sought to tamp down expectations.

The moderate economic growth the Fed expects will lead to only a slow decline in the nation's nearly double-digit unemployment rate, he said.

He offered no new clues about the timing of an interest rate increase. Most economists think it is months away. Bernanke said rates will need to stay at exceptionally low levels for an extended period "as the expansion matures."

Investors seemed buoyed by Bernanke's commitment to low rates. In afternoon trading, the Dow Jones industrial average rose 87 points. The stock pickup came despite a government report showing sales of new homes fell to a record low in January.

Bernanke is facing more pressure than usual from lawmakers in an election year. Their constituents are struggling economically, while bailed-out Wall Street banks are profitable again. Unemployment stands at 9.7 percent, home foreclosures are at record highs and individuals and businesses are having trouble getting loans.

"Getting people back to work — socially, most of all, but also for the overall economy" — is critical, said the committee's chairman, Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass.

To help make that happen, the Senate passed a bill Wednesday aimed at spurring job creation. The legislation would give tax breaks to businesses that hire the unemployed.

The Fed chairman reiterated a pledge that the Fed will keep its main interest rate at an all-time low near zero for an "extended period." The target range for Fed's main rate, the federal funds rate, has been between zero and 0.25 percent since December 2008.

At the same time, Bernanke sought to stress that when the economy is on firmer footing and the Fed needs to reverse course and tighten credit for millions of Americans, he will do so.

Deciding when to boost rates will be the next big challenge facing Bernanke. Boosting rates too soon could derail the recovery. But waiting too long could trigger inflation and feed a speculative asset bubble. That, too, could threaten the economy, along with Americans' pocketbooks and nest eggs.

Bernanke would only say that "at some point," the Fed will need to move to tighten credit. When it does, Bernanke sketched out the Fed's strategy, first unveiled on Feb. 10, for doing so.

He said the Fed is likely to boost the rate it pays banks on money they leave at the Fed, which would mark a shift away from the funds rate, the Fed's main tool since the 1980s. A bump-up in the interest rate on bank reserves, though, would ripple though the economy in much the same way an increase in the funds rates does. Consumer and businesses borrowers would have to pay more for loans.

With financial conditions improving, the Fed has been able to wind down most of its special lending programs for banks and others set up during the crisis.

One key economic revival program that has lowered mortgage rates and bolstered the housing market is slated to end on March 31. The Fed is on track to complete buying $1.25 trillion worth of mortgage securities from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac at that time, and another $175 billion worth of debt from them.

Bernanke said the end of that program would have only a "modest effect" on pushing up mortgage rates. He continued to leave the door open to a possible extension of the program if the economy were to take a turn for the worse.

Asked whether the Fed's low rates are risking a new speculative bubble, Bernanke said he didn't see any "obvious bubble" forming in the U.S. economy.

The Fed's decision last week to raise the rate banks pay for emergency loans was part of a broader strategy to bring lending closer to normal now that the crisis is over, he said. The bump-up in the "discount" rate should not be seen as a signal that tighter credit for consumers and businesses is imminent, Bernanke added.

To help improve relations with Congress, Bernanke said the Fed will seek to be more open about its operations. He said it would support legislation to identify companies that used the Fed's special lending facilities — "after an appropriate delay." A delay in identifying the companies would help discourage investors from viewing a company as having financial troubles, he said.

But Bernanke said the confidentiality of banks drawing emergency loans from the Fed's "discount window" must be preserved. The Fed acts as lender of last resort for banks that can't get money from private sources. Bernanke said identifying banks that draw emergency loans could cause a run on those institutions and undermine the program. Healthy banks are key to a sound economy.

Rep. Ron Paul, R-Texas, who's led efforts in Congress to audit the Fed, accused it of a "cover up" involving details of bailed-out companies and users of its lending programs. Bernanke called those allegations "absolutely bizarre" and added: "I have absolutely no knowledge of anything remotely like what you just described."

Pressed by Paul on whether the Fed has discussed a bailout of Greece, which is suffering a debt crisis, Bernanke said no.

Republicans on the panel, in particular, expressed concern about record-high federal budget deficits, which Bernanke agreed must be reduced over time.

The deficits are the "elephant in the room," said Rep. Spencer Bachus of Alabama, the committee's senior Republican.

Bernanke urged Congress to move ahead on revamping the nation's financial structure to prevent a repeat of the events that thrust the economy into recession in December 2007. The Fed is working to improve regulatory oversight and is developing a program to better police large bank holding companies, he said.

The Fed's lax regulation and failures to spot problems were blamed by lawmakers for contributing to the financial crisis. Some want to strip the Fed of its banking powers and place it under greater oversight. Bernanke opposes taking away the Fed's banking supervision, saying it would hurt its ability to carry out interest rate policy.