Everyone in the room knew it was over.

First one side, the U.K. one, had seen its CEO ousted. Now the other side, the U.S. one, was about to see its CEO head for the exit, too.

It was September 2021, and the end was near for Dick Weil, the American who’d deftly maneuvered his way to the top of a transatlantic amalgamation of two famous if faded names in mutual funds.

One of those names is Janus, the company Weil used to run out of Denver that reached the zenith of its fame in the dot-com 1990s. The other is Henderson, a London outfit originally established to mind the legacy of Sir Alexander Henderson, 1st Baron Faringdon.

Today, five years and soon-to-be three chief executives into a self-described “merger of equals,” Janus Henderson Group Plc is struggling to show just how the tie-up will pay off for customers and shareholders.

Weil was brought down by what’s become a fumbling attempt to unite the two companies. His antagonist at that September meeting in London: power investor Nelson Peltz. After amassing a sizable stake in Janus Henderson, Peltz quickly lost patience with Weil, and the feeling was mutual, insiders said. Weil stepped down in March. AllianceBernstein Holding LP Chief Financial Officer Ali Dibadj, who has a history with Peltz and his firm, is due to take over as CEO next month.

The following tale of hubris, alliances and intrigue is based on interviews with more than a dozen current and former Janus Henderson employees, who asked not to be identified to avoid hurting their careers.

First Weil moved to London from Denver in style — the relocation cost almost $1 million. Then he began to outflank his U.K. counterparts in the Henderson camp.

Inside 201 Bishopsgate, Henderson’s City of London headquarters, doubt and mistrust began to spread soon after the merger. Cracks formed between the two sides, and the Henderson crowd’s worst suspicions seemed to be confirmed in July 2018 when Weil beat out co-CEO Andrew Formica — the Henderson chief who’d initiated the merger — after the company decided it wanted a single leader.

Now Weil, 58, is also out, and it’s left to someone else to prove they can confront the sobering reality of today’s mutual-fund business. The merger — and Peltz’s wager on the combination — rests on a bedrock belief that people will pay for funds that actively manage investments rather than simply hew to market indexes. But that idea comes as the passive approach slowly eats up market share, from 42% of all funds two years ago, to 46% today, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

People close to Peltz, the corporate shakeup artist of Procter & Gamble Co. and PepsiCo Inc. fame, said he’s betting the active/passive tide will turn when the markets do, as they have this year with vengeance.

But so far, the Janus-Henderson merger has been a loser by almost any measure.

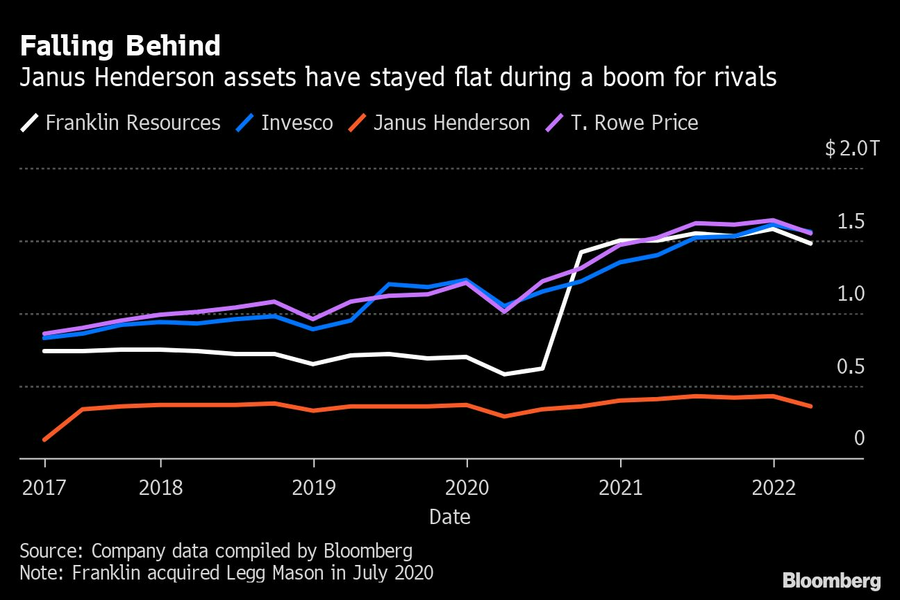

Money has flowed out of its funds for 18 consecutive quarters. Despite once-heady markets that lifted asset values industrywide, Janus Henderson manages about $360 billion, only marginally more than it did at the time of the merger. Its stock price, meantime, has fallen 10% since the combination. Rival T. Rowe Price Group Inc. gained 74% over that period.

Weil, still in London, said he had laid the groundwork for the future and felt the time was right to move on.

“My leadership team had instilled a unified employee culture of excellence and led the consolidation across the business and, as a result, we built a strong foundation to support future growth,” he said in a statement.

Janus Henderson speaks a similar language.

“Over the past five years we have made significant progress establishing a strong foundation which positions the firm well for the future,” the company said in a statement for this story.

“We are excited to welcome our new CEO in June, we are ready to drive Janus Henderson’s next phase of growth and look forward to continuing to create value for our clients and shareholders.”

Formica declined to comment, as did Peltz.

It was 2016, and Formica, then head of Henderson Group, was eager to expand his reach into the U.S. — to build, at long last, a truly global fund company eight years after he had taken the reins at the tender age of 37.

Staff mostly liked him. Energetic and approachable, with an easygoing Australian informality, Formica had a knack for mingling up and down the ranks inside 201 Bishopsgate. He liked to walk the floor and spend time with investment and sales teams.

Now, he had reason to make his move. Henderson seemed to be in solid shape. As CEO, Formica had undertaken several modest acquisitions, strengthening the firm’s foothold in Continental Europe and expanding in Asia and Australia.

Yet Henderson was still a small player on the global scene, and a pipsqueak next to multitrillion-dollar giants such as BlackRock Inc. and Vanguard Group. If Henderson, founded in 1934, didn’t buy someone else, the thinking went, it might become takeover bait itself.

Enter Janus. No one under the age of 40 might remember this, but Janus fund managers used to blow away the competition. After the great Nasdaq collapse of 2000, however, it never regained its former glory. Quite the opposite: In the years that followed, it spiraled down and down. By the time Weil arrived in 2010, from Pacific Investment Management Co., it was struggling to attract new client money, and its stock had languished for years.

Weil, a lawyer and boardroom networker, rather than an investment savant, kept reminding people that he’d come from the mighty Pimco, which had turned sleepy bond investing into a cutthroat trillion-dollar business. He vowed to work similar magic at Janus. (Years later, he even picked up Pimco legend Bill Gross, the one-time Bond King. But Gross, like Janus, couldn’t relive past glories, and would retire after a few lackluster years. He declined to comment.)

And so, gazing across the Atlantic. Formica thought Henderson had the upper hand, and that his firm would grab Janus.

But once Britain broke with the European Union in 2016, shocking London finance and dragging down both the pound and stock prices, Formica’s dream acquisition turned into a “merger of equals.” After months of discussions between the two CEOs, Janus and Henderson announced they would combine in an all-stock deal.

Initially, the board considered having Weil run the company for a few years before handing the reins to Formica. Instead, Janus Henderson opted for co-CEOs, an arrangement that often becomes fraught.

Inside the London headquarters, a joke began to make the rounds: The new Janus Henderson felt like Noah’s Ark. Everywhere executives went, they seemed to move two by two, one from the Janus side, one from the Henderson side.

Janus Henderson maintained two identical technology teams, two heads of facilities, two heads of HR, two heads of products. On and on. Instead of reducing redundancies and inefficiencies, the merger had added to them, starting at the very top, with two CEOs.

But the dual leadership was seen as dysfunctional, and amid the firm’s struggles it descended into a period of politicking between rival factions.

Some rank-and-file employees said they were rooting for Formica. To them, he seemed to have a firmer grasp of fund management than Weil, and he came across as a nicer guy. On a visit to Denver, Formica had the interior stairwells heated and carpeted — a small gesture that the staff appreciated. Another time he hopped into an employee’s Honda to hit the phones at a Janus call center, the sort of place Janus higher-ups rarely visited.

But while Formica was popular, some portfolio managers felt their personal fortunes would be better under Weil, according to people with knowledge of the matter. Ultimately, the board sided with Weil. His lawyerly manner and knack for corporate maneuvering helped him be seen as the safer option, according to some of the people. Formica, the Henderson CEO who’d dreamed of building his empire, was out.

Insiders said the firm’s new leaders soon came to be viewed with suspicion, even animosity, by many in the Henderson camp. These people — some of them concede they’re still embittered — said the executives did little to set the company apart from the competition. Formica, who’s now CEO of Jupiter Fund Management Plc, is said to stand by his rationale for pursuing the Janus deal. Unsurprisingly, he is also said to regret the board’s decision, as well as the departure of key Henderson people.

Even pro-Weil executives said Janus Henderson failed to move quickly to sort Intech Investment Management, a quantitative equity subsidiary that was finally spun off earlier this year. Weil also could’ve done more with technology, these people said.

But portfolio managers also took away an uncomfortable message from Weil’s chief investment officer, Enrique Chang.

Chang spoke often of limiting the volatility of performance, which left some portfolio managers with the impression that they should stick closer to benchmarks and do less of what they were supposedly good at: picking winning investments. While Chang denies promoting that idea, many employees saw it as caution aimed at preventing more client money from walking out the door.

“I wanted to have superior — so more than benchmark returns — long-term, risk-adjusted returns,” Chang, 59, said in an interview. “So definitely beat the benchmarks, and be active investors, and do so in a way that is very much taking the risk that they have in the portfolios into account.”

As Janus Henderson’s share price sank, some staffers began circulating a chart that compared the decline in the company’s market value to the gain in the S&P 500 — and Weil’s compensation. Since the merger he has taken home about $50 million, according to company statements.

Those more sympathetic to Weil said he was taking on unglamorous administrative tasks and focusing on the big picture, as CEOs should.

Peltz was watching. His Trian Fund Management had begun buying Janus Henderson shares in 2020.

Peltz, 79, believes active fund management will stage a comeback, according to people familiar with his thinking, and that Janus Henderson’s research teams and sales network will help it benefit when that happens.

At that September meeting in London, Peltz pressed Weil to justify his strategy, but he wasn’t satisfied with what he heard. Weil, for his part, was cautious given Trian’s stake in Invesco. (At that stage Trian also had Invesco board seats). Peltz quickly concluded that Weil was no longer the person for the job. Even Janus Henderson insiders who said Weil did the best he could concede his position had become untenable. Before long, Chang was also out.

The next CEO, Dibadj, certainly has Peltz’s backing — Trian welcomed the appointment, and referred to a relationship that goes back more than 15 years. The new man is said to have made a good impression on recent visits to Denver and London, but no one is under any illusions about the size of his task. Since the merger, the firm has seen $100 billion of client money head for the exits.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound