Nearly a decade after arriving in Europe’s exchange-traded fund market, Vanguard Group doesn’t have to look far for reminders of just how tough it can be.

The investing giant’s first European ETFs turned eight last month, but the company’s performance in the region will surely have put a damper on any celebration. Vanguard products bled more than 600 million euros ($670 million) in May, their first losing month in 10 and the worst since 2018.

Compare that with the American market, where Vanguard trounced all its competitors, spurring talk it could even overtake BlackRock Inc. to become the largest asset manager globally.

It’s a disconnect that perfectly illustrates the challenges facing even the biggest names trying to crack the world’s second-largest ETF market, and one of its fastest-growing.

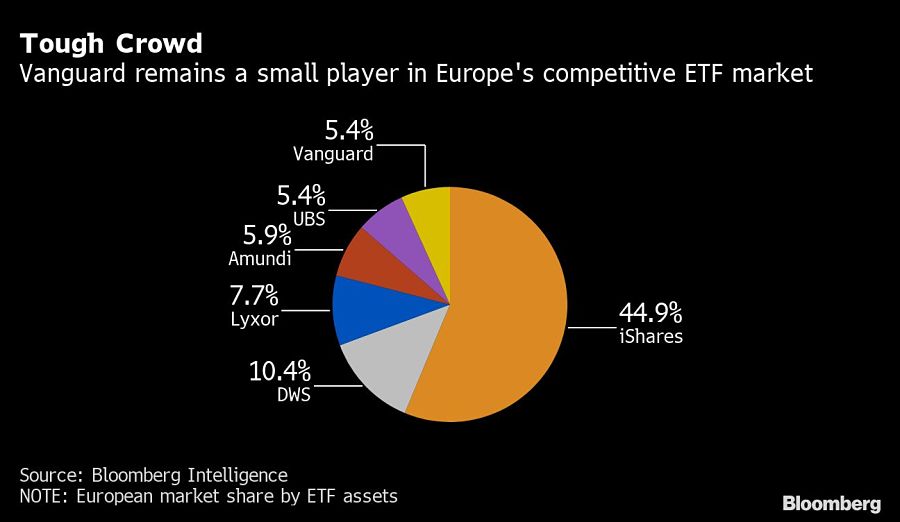

Vanguard’s retail-friendly message has won it a loyal following among small investors in the U.S., who have plowed about $1.1 trillion into its funds. But the same philosophy has so far fizzled in Europe, where the company has less than 6% of the market compared with first-placed BlackRock’s 45% share. In America the figures are more like 27% and 38%, respectively.

Arguably the biggest problem facing the $6.2 trillion behemoth is that the European financial landscape is dominated not by moms and pops but by institutions. This means issuers with long-standing distribution strategies directed toward these players have thrived, while retail investor-oriented outfits like Vanguard have struggled.

Since its 2012 arrival, the company has collected around 47 billion euros into its Europe-listed ETFs, leaving it in sixth place in the $1 trillion market. That puts it behind not only global leader BlackRock but also homegrown players DWS Group, Lyxor Asset Management, UBS Group and Amundi.

Still, the company founded by John Bogle has no plans to abandon its long-standing philosophy, said Thomas Merz, head of distribution for continental Europe.

“We didn’t adjust to the European market, we didn’t have hundreds of different ETFs slicing and dicing the market in a narrow way as often is the case for Europe with other ETF providers,” he said. “We haven’t changed our Vanguard approach.”

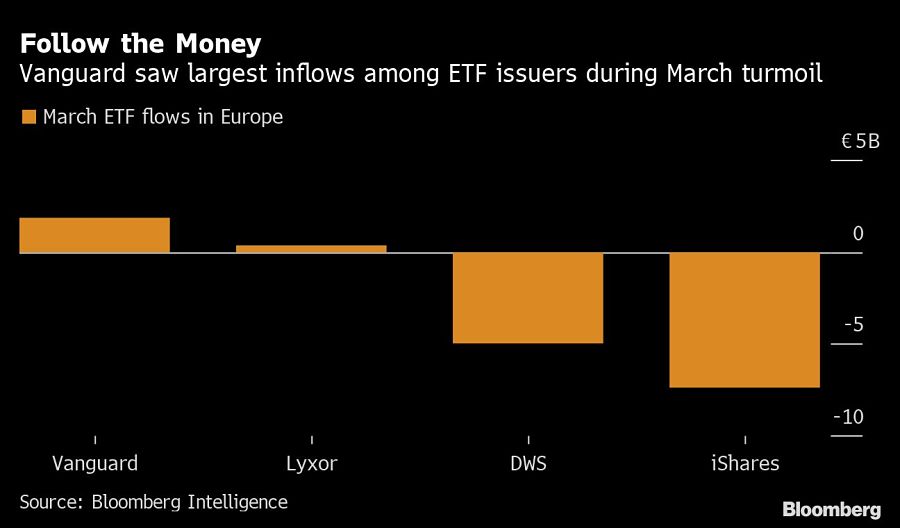

There have been glimpses the strategy could yet prevail. Overall inflows for the year remain solid at 3.6 billion euros, with the company performing especially well during the height of the coronavirus crisis in March. It lured 1.8 billion euros that month, while virtually all of its competitors saw outflows.

Vanguard’s own May outflow is a reminder that plenty of legacy issues remain. Unlike local players such as UBS and DWS, the American company doesn’t have a private wealth or retail banking division. That’s barely a factor in the U.S., but in Europe it means competitors have a deep customer base to sell ETFs to.

“If you’re a German millionaire, chances are that you have a long-time family relationship with a banker, and that banker is the one picking products, and chances are that they’re putting you into that bank’s products,” said Dave Nadig, chief investment officer and director of research at ETF Flows. “That’s a very, very tough market to crack.”

It’s a disadvantage for new entrants that shows few signs of disappearing soon.

Credit Suisse Group announced earlier this year that it’s converting several of its index funds to ETFs as it looks to capitalize on its own massive private bank. That marks a return to the market a decade after the Swiss bank sold its old business to BlackRock -- and means yet more competition in an already crowded field.

If there’s an abundance of issuers in Europe, it’s nothing compared to the proliferation of products. BlackRock alone offers several hundred, holding everything from corporate bonds that have lost investment-grade ratings to Italian mid-caps. Amundi has about 150, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. These lineups appeal more to hedge funds and asset managers who invest tactically than the kind of broad, diversified index-tracking funds on offer at Vanguard, which has just a few dozen vehicles in Europe.

“They’re not in favor of product proliferation, they’re all about scale,” said Hortense Bioy, director of passive funds and sustainability research in Europe for Morningstar. “You won’t go to Vanguard if you’re looking for something specific, so it’s hard for them to catch up with other players.”

It’s all about staying faithful to Vanguard’s strategy of focusing on broad-based building blocks. The company wants to help investors construct “simple and cost-efficient” portfolios, he said, in keeping with Bogle’s philosophy of investing only in what you need.

Vanguard has consistently pushed that message, including starting a web and TV ad campaign earlier this year in the U.K., where it offers an online platform that lets self-directed investors trade its ETFs. It also slashed fees on several U.K.-listed funds in October. The nine months of consecutive inflows before May -- plus the huge March outperformance -- may be evidence that the message is gaining traction.

The question remains whether the mom-and-pop crowd -- and hence Vanguard -- can ever meaningfully upset the dominance of Europe’s big money players.

“It can be difficult for any non-European company to penetrate,” said Morningstar’s Bioy. “It’s a different market.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound