The October edition of the latest in financial #AdviserTech kicks off with the news that DPL Financial Partners has raised $20 million of capital to continue scaling up its marketplace of no-commission annuities for registered investment advisers, as the ongoing development of new fee-based products — combined with deepening tech integrations for annuities into existing RIA systems — is leading to a steady rise in the use of annuities by RIAs, with more than $1 billion of new flows via DPL in just the past 12 months alone.

Notably, the fresh capital comes in the midst of a recent rise in interest rates that may, for the first time in nearly 15 years — since before the financial crisis — give annuity products enough yield to be able to innovate new offerings and more competitive pricing. The growth of DPL’s marketplace may itself usher in a greater level of annuity competitiveness, as companies are forced to compete for RIA attention not by offering the biggest commissions but by offering the best features and benefits to get through the RIA-as-gatekeeper.

From there, the latest highlights also feature a number of other interesting adviser technology announcements, including:

• Ethic Investing raises a $50 million Series C round as values-based “personalized indexing” through direct indexing tools continues to gain momentum.

• Wealthfront’s acquisition deal with UBS falls through as incumbents continue to show they’d rather build than buy (at least at robo-adviser valuations).

• Morgan Stanley rolls out a held-away account aggregation feature for its 401(k) plan advisers to provide more holistic advice within the plan to participants (before they ever have a chance to roll over to an independent adviser in the future).

Read the analysis about these announcements in this month's column, and a discussion of more trends in adviser technology, including:

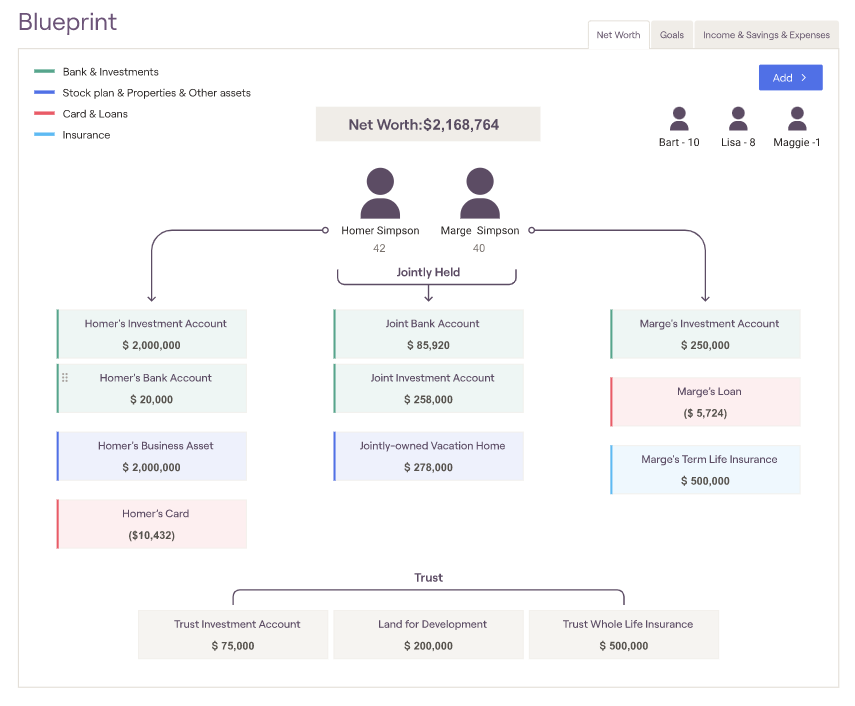

• RightCapital launches a new Blueprint feature to create an asset-map-style visualization of the client’s financial household.

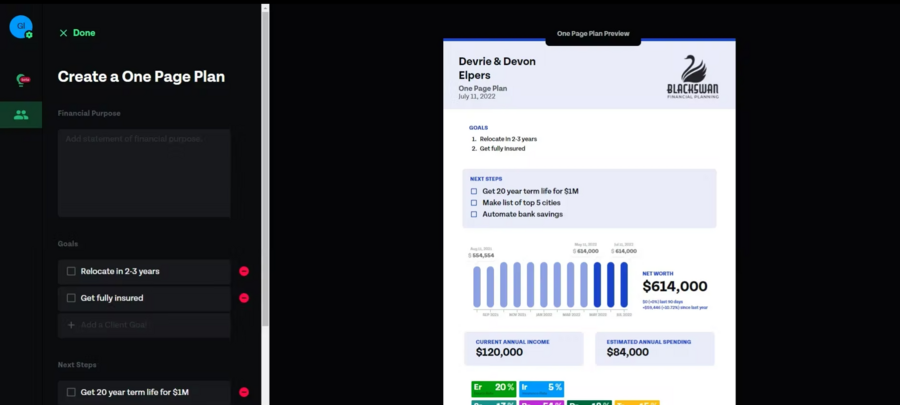

• Elements creates a one-page financial plan solution, not to replace the traditional financial plan, but to engage clients more meaningfully and even prospects with a better financial monitoringprocess until it’s time for their next financial plan update.

In the meantime, we’re also gearing up later this month for several new updates to our new Kitces AdviserTech Directory, including Adviser Satisfaction scores from our Kitces AdviserTech Research and Integration scores from Ezra Group’s research.

And be certain to read to the end, where we have provided an update to our popular “Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map.”

AdviserTech companies that want to submit their tech announcements for consideration in future issues, please submit to TechNews@kitces.com.

Annuities have struggled for years with the unfortunately earned perception that they are high-cost products, driven in large part by the often sizable commissions that are paid to annuity agents who sell them. The situation was further complicated in the wake of the financial crisis, when the Fed cut interest rates so low that there just wasn’t much room left for annuities to pay much in interest (or to have much interest yield available to provide other types of returns or income guarantees).

Yet agents still expected to get paid to sell the contracts, which means products increasingly became more complex and more opaque as a means to mask how little return potential would be on the table in a low-rate environment. In the aggregate, it appears that consumers weren’t fooled all that much, as according to Limra, total annuity sales in 2021 were $255 billion — a growth rate of 0% over the preceding 14 years since the financial crisis, when total annuity sales were $257 billion in 2007.

RIAs, in particular, have spent much of the past two decades selling heavily against annuities’ often-high costs. From Ken Fisher’s infamous “I Hate Annuities” campaigns, down to the individual RIA that simply tries to show how a low-cost portfolio, plus the adviser’s own fees, still may add up to far less than the cost of an annuity and without the challenges of illiquidity (surrender charges), limited investment options or contracts too opaque to even fully understand how they work in the first place.

However, the reality is that annuities are not inherently bad. They’re a tool, and one that doesn’t have to be designed and priced the way that they are. Instead, product pricing and design have been a function of how annuities were distributed — through annuity salespeople.

This began to change when the Department of Labor issued its fiduciary rule in 2016 and raised the prospect to annuity carriers of a potential future where annuities couldn’t be sold by commission-based salespeople, and might have to be sold by fiduciary advisers. Coupled with the ongoing growth of the fiduciary, no-commission RIA channel, and the 2019 issuance of a private letter ruling from the IRS that RIAs could have their fees withdrawn directly from annuities on a pretax basis, fee-based annuities for RIAs are now gaining momentum.

This provides context for this month’s news that DPL Financial Partners — which has created a fee-based annuity marketplace for RIAs, and the supporting consulting/expertise services that annuity-unfamiliar RIAs would need — announced a new $20 million round of capital to continue scaling up its RIA annuity marketplace, having surpassed $1 billion in new annuity flows in the past year.

From the adviser perspective, more funding for DPL means an expansion to its already sizable 85-person head count to support the growing service demands of advisers as well as investments into DPL’s technology, and likely investments into its own marketing and sales efforts to reach more advisers.

From the broader industry perspective, though, arguably the greater significance of this news is that as DPL continues to grow and gain momentum and demonstrate that RIAs arewilling to buy more competitively priced, client-centric annuities, it forces more annuity carriers to recognize the growth potential of the RIA marketplace. This means even more fee-based annuity offerings for RIAs (beyond the reported 25 carriers and 70 products that DPL already offers), and more competition among carriers for adviser attention. This tends to further bring down costs and improve benefits for the end client, given the fiduciary-gatekeeper approach of RIAs, in a positive feedback loop. Especially recognizing how big the RIA growth opportunity is — where DPL’s $1 billion of fee-based annuities is still just a drop in the bucket for an annuity industry with over $250 billion of new flows last year, which itself is minuscule relative to the more than $5 trillion that independent RIAs and hybrids currently control.

Despite its sizable funding and growth momentum, arguably DPL still has an immense amount of room to grow and has only barely scratched the surface. The only real question now is how far RIAs will really go with an increasing range of annuity products available at increasingly competitive prices — a transition that may be further catalyzed by rising interest rates, which for the first time in nearly 15 years will provide annuity carriers with enough yield to be able to design a potential new wave of fee-based annuity product innovation.

Direct indexing has existed in some format for nearly 30 years since it was pioneered by firms like Parametric and Aperio, who offered ultra-high-net-worth investors the opportunity to replace their core holdings, like an S&P 500 index, with the 500 individual stocks ofthe S&P instead, creating the potential to engage in tax-loss harvesting at the individual stock level. As a result, even if the S&P in the aggregate was up for the year (which means there’s no opportunity to engage in loss harvesting on an index fund), if 150 of the individual stocks within the index had losses, the direct-indexed, ultra-HNW investor could harvest those individual stock losses — typically at top tax brackets — for immediate tax savings, while continuing to hold onto and not trigger gains on the other 350 stocks that were up.

Notably, though, for most of its history, direct indexing was an ultra-HNW solution. In part, that’s simply because tax-loss harvesting produces more tax savings for those who are in higher tax brackets in the first place. Also, allocating a portfolio across 500 individual stocks could entail a nontrivial amount of trading costs if each stock trade cost $19.99, $9.99 or even $4.99 per trade (as ticket charges came down over time), such that investors had to have a sufficiently large allocation to ensure that racking up 500 ticket charges wouldn’t materially or fully offset the tax savings.

However, the dynamic was forever changed when, in October 2019, Schwab announced that it was cutting stock trading commissions to $0, setting off a chain reaction where most competing brokerage firms quickly matched the offer. Suddenly, there was no longer a cost to trade any — or very many — stocks. In the new world of zero commissions, direct indexing was no longer constrained to those who had a large enough portfolio for the tax savings to beat the trading costs. In fact, it was no longer constrained to be just a tax-loss-harvesting strategy in the first place.

As a result, in recent years four different types of direct indexing strategies have begun to emerge: tax-focused (where direct indexing is used primarily for tax-loss harvesting, and other individual-stock-related tax strategies like donating appreciated stock for charitable purposes); personalized preferences (where direct indexing is used to create a stock allocation based not on broad-based indices but on the client’s own individual values and preferences); rules-based (where direct indexing platforms are used to implement rules-based investment strategies like factor investing or other smart beta approaches); and customized portfolios (created around specific client constraints, like completion portfolios around an existing legacy stock, or building a portfolio for a partner at a public accounting firm who can’t own certain stocks that their company audits).

And last month, Ethic Investing — one of the early players in the category of personalized (values-based) direct indexing — announced a whopping $50 million Series C round of funding to continue to scale up its direct indexing platform for advisers, having nearly doubled in 12 months from $1 billion of AUM in April 2021 to nearly $2 billion by March of this year. At a fee schedule of 0.2% (for standardized market theme solutions) to 0.4% (for fully custom values-based portfolios), that implies a run-rate revenue of $6 million to $8 million earlier this year, and a very heady valuation albeit one that may be quickly rationalized at 100%-plus growth rates.

What’s notably unique about Ethic — in an increasingly crowded space of direct indexing providers — is that the platform has stayed rather tightly focused specifically on its values-based investing approach, with an interface built specifically to help clients articulate the causes that are important to them, develop a portfolio built around those values, and actually quantify the impact of those investments (e.g., how the portfolio’s reduced carbon impact is equivalent to taking X cars off the road, or its water savings is the equivalent of cutting out Y showers).

This is unique because most direct indexing platforms have tried to check off all four types of direct indexing at once and in the process, have not created an especially compelling or effective user experience for any one of them that is persuading advisers to make the shift. In other words, Ethic has excelled not by trying to optimize for all the direct indexing use cases, but by building a strong user experience to excel at one in particular, in a manner that is actually getting advisory firms to adopt.

Ultimately, it remains to be seen just how much demand there is from consumers — and thus the financial adviser community that serves them — when it comes to creating more values-based portfolios. But given ongoing generational research indicating that millennials in particular care a lot more about aligning their portfolios with their values and seeing their capital allocated to causes that they want to see advanced, even mega-firms like Schwab are making a big bet on a personalized indexing solution. With the rapidly emerging growth of platforms like Ethic, it appears that a more personalized values-based investing approach is a new version of direct indexing that is here to stay. The only question is which client segments in particular will want to adopt this approach.

When robo-advisers first burst onto the scene nearly a decade ago, they framed themselves as the great disruptor of the status quo, claiming that they could provide the same services that human financial advisers provide for one-fourth the fee, and in doing so would be able to take down Wall Street. In fact, in the early years, then-Labor Secretary Perez outright touted Wealthfront as a lower-cost fiduciary alternative to traditional Wall Street.

The caveat, though, is that as the number of robo-advisers proliferated, consumers increasingly had to vet various robo-adviser options and choose which one had the best investment management solution — a decision not dissimilar to what consumers already faced in trying to pick a mutual fund or ETF. This meant that in practice, robo-advisers were not actually appealing to delegators who hire human financial advisers because they don’t want to make those investment choices themselves Instead, they were primarily serving do-it-yourselfers who like to research investment alternatives and make their own choices.

As a result, it was largely the DIY solutions — most notably, Schwab and Vanguard — that were the first to launch competing solutions in response, including Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolios and Vanguard’s Personal Advisor Services. The incumbents had one immense advantage — an existing base of retail DIY investors to whom the solution could be cross-sold, rather than needing to market their solution to new investors who would have to open new accounts and move their money. In the end, it's not the operational costs but the client acquisition costs that most drive up the cost of financial advice.

Within a few years, almost every pure robo-adviser but the original two — Wealthfront and Betterment — had been driven out of business because of those prohibitive client acquisition costs, and the last two were looking for an exit. Then Wealthfront managed to queue up earlier this year when UBS announced that it would acquire the platform for $1.4 billion. This is a rather stunning amount given that Wealthfront at the time had approximately $28 billion of reported assets, which at its 0.25% advisory fee would amount to about $70 million in gross revenue, or a valuation of nearly 20 times revenue. Ostensibly UBS hoped to justify that by being able to proactively cross-sell Wealthfront to their existing UBS clients (similar to how Schwab and Vanguard had prevailed with their offerings), with a significant portion of the Wealthfront valuation reportedly tied to post-closing bonus payments that would be made if/when/as certain performance targets were hit.

Except even more surprising news hit that the UBS-Wealthfront deal had fallen apart, and instead UBS would just be making a $69.7 million investment into Wealthfront at its $1.4 billion valuation, while Wealthfront would remain on its independent course. The big questions now are: “What happened?” and “What does this portend for the valuation of robo-advisers in the future?”

Notably, a lot has changed in the nearly nine months since the UBS-Wealthfront deal was first announced. Markets have tumbled more than 20% as inflation spiked and the Fed began to raise rates. Outflows and attrition are likely up because client turnover typically increases in a bear market. Rising interest rates have changed the cost of capital that fuels valuation multiples. And fintech valuation multiples themselves have compressed industrywide.

It's also notable that this summer, UBS announced that Naureen Hassan will become its new president of UBS Americas. Hassan is widely known as one of the key architects of Schwab’s original Intelligent Portfolios platform, and then went to Morgan Stanley, where she helped to drive its popular “Next Best Action” initiative as the firm’s chief digital officer. This means Hassan knows exactly what it takes to build and roll out digital tools within a mega-enterprise like UBS. Is it possible that Hassan recognized that even with the challenges of the “innovator’s dilemma,” UBS could build an internal solution — or better leverage its existing SigFig partnership — rather than to acquire Wealthfront for $1.4 billion?

It's also entirely possible that the UBS-Wealthfront deal blew up for some other reason, unknown to any. The reality is that such deals typically require a “material adverse event” to be cut short, for which a change in leadership or change in market conditions alone is usually not sufficient. Or perhaps the market downturn simply made the post-closing growth targets so impossible that Wealthfront wanted out (realizing it may no longer be able to hit its post-deal performance targets) while UBS also wanted out (for the aforementioned reasons), and a funding round of just $70 million was a mutually face-saving resolution (allowing UBS to risk only $70 million instead of $1.4 billion, and providing Wealthfront with enough runway to keep growing independently and try to establish an even higher exit valuation some number of additional years in the future).

In the end, though, the real moral of the story is simply that the financial services industry incumbents are far larger than almost anyone truly realizes, to the point that companies like Schwab and Vanguard could wait 3-plus years and still quickly leapfrog well-funded robo-adviser startups. Even 10 years later, the incumbents are still making the decision that it’s faster to build internally than to buy. When it comes to the financial services industry, the key to success is not disruption of an industry with incumbents so large that they can buy or build themselves long before they’re ever disrupted, but capitalizing on the incremental evolution that is very slow from year to year but absolutely immense with long-term compounding.

Since the arrival of the first RIA custodial platforms in the early 1990s, the growth of the RIA movement has been all about the growth of assets under management, as investors have increasingly shifted from working with brokers (where the customer retains the decision about whether to purchase the investment being sold, or not) to working with advisers (where the adviser has discretion to manage the client’s investment accounts on their behalf). This led RIAs to be increasingly focused on working with prospective (near-)retirees, both because retirees tend to have more assets available to manage (that they accumulated over the decades), because retirement itself is a major life transition (where consumers tend to seek new services and new providers), and perhaps most importantly because most consumers can’t actually work with an adviser untilthey retire, as the typical adviser can’t actually mange assets in an employer retirement plan itself (only once those assets are able to be rolled over into an IRA).

The challenge, however, is that there are only so many prospective retirees ready to retire and roll over their employer retirement plans in any particular year, and competition for those retirees' rollovers has become increasingly intense as more firms try to win their business. As a result, a growing number of large enterprises are now trying to capture the attention of prospective retirees long before they’re actually ready to retire by providing advice services into401(k) plans themselves. Thus, Financial Engines’ acquisition of Edelman, Empower buying Personal Capital, and Morgan Stanley purchasing ETrade (which was not just about acquiring ETrade’s retail brokerage business, but perhaps more importantly its stock plan administration business, which now gives Morgan Stanley access to employees who have stock options and restricted stock being administered by ETrade, otherwise known as upwardly mobile, rising-asset pre-retirees).

At the same time, advisers have faced a growing pressure to do more to show their value and justify their ongoing advisory fees. This means providing advice on more than just the portfolio the adviser manages, and may include more comprehensive financial planning beyond the client’s investments, and/or advice on held-away assets that aren’t being managed by the adviser directly and instead are simply advised upon (where the adviser may provide investment recommendations that the client subsequently implements themselves). That’s leading to an emerging shift from AUM to AUA,

In September, Morgan Stanley announced a new integration that will account-aggregate the held-away employer retirement plan assets of client accounts directly into its Corporate Retirement Portal for advisers serving retirement plans. This allows the advisers to get a more holistic view of all of the assets (and advice opportunities) of their plan participants. It also connects to Morgan Stanley’s “Next Best Action” engine, which tries to spot meaningful opportunities for advisers to engage in proactive outreach to clients on investment issues (e.g., by spotting that a client has a concentrated position in a held-away account and prompting the adviser to reach out to the client when that company has a significant news event).

From the Morgan Stanley perspective, the new technology provides the firm with even more opportunity to shift its existing employer retirement plan relationships from just being plan participants into more holistic client opportunities — where it’s actually the traditional investment accounts that are held-away and can be aggregated intothe (usually much larger) retirement plan relationship. This deepens the advice relationship to the point that when it’s time to retire, plan participants can simply continue with their existing Morgan Stanley adviser. This improves the long-term opportunity of the investments that Morgan Stanley has been making in its acquisitions of employer retirement plan businesses (including Solium’s stock plan business, ETrade’s stock plan business, Cook Street Consulting and American Financial Systems).

From the broader industry perspective, though, it’s hard to understate the significance of firms at the size and scale of Morgan Stanley making such substantial investments into turning the traditional employer retirement plan and stock plan administration business into more holistic advice offerings. The firm’s acquisitions in recent years represent more than $100 billion of what might have otherwise been future retirement plan rollovers that might not be anymore because Morgan Stanley will have years to establish advice relationships before those prospective retirees ever hit the radar screen for a traditional adviser. This can change the entire nature of how independent advisers find and obtain (or cannot obtain) new clients in the coming decade.

In the early days of financial planning, many households had no idea what they were actually worth. Financial accounts were splintered across multiple banking and brokerage institutions; mutual funds and even individual stocks might be held directly with the companies; insurance lived in its own silo. As a result, one of the key benefits of going through the financial planning process and getting a financial plan was simply that it provided — for many, for the first time ever — a single consolidated balance sheet that reflected their entire household finances.

Over the years, the process of gathering financial data became easier as software rose to the challenge, automated by account aggregation, from Mint.com for consumers to eMoney for financial advisers. This began to turn the tracking of a client’s household wealth into a value-add that could be provided over time, and not just as part of the upfront financial planning process.

The caveat, though, is that the classic balance sheet is arguably not necessarily the best way to help clients visualize their net worth. After all, the balance sheet originated as a way for accountants to report on the value of a business enterprise and not necessarily as a way for a not-necessarily-as-financially-sophisticated individual household to visualize its finances. This is especially true when there are multiple members of a household in which not all assets may be evenly split. Not to mention that a classic balance sheet only looks at the household’s assets and liabilities and not necessarily its income (which traditionally is a separate report — the profit and loss statement).

In recent years, this led to the growth of alternative ways to help clients visualize more of the big picture, such as the adoption of “mind mapping” techniques by financial advisers. Except traditional mind mapping is hard for advisers to create — especially on the fly with clients — and mind mapping has historically been focused more on creating a holistic view of concepts and how they’re interconnected, and not necessarily on visualizing the breadth of a household’s finances (which still entails a lot of numbers). That’s a gap that ultimately Asset-Map began to fill by adopting a more mind-mapping-style approach to create a one-page visualization for advisers (and their clients) of a household’s assets and liabilities, as well as income and expenditures, and other key details such as insurance coverage.

Last month RightCapital announced the launch of its own version of a holistic mind-map of the client’s household finances, dubbed Blueprint. Notably, RightCapital’s approach isn’t quite the same as Asset-Map’s. Instead of a single-page visualization, RightCapital’s Blueprint is three pages, with one reflecting household net worth, a second for the client’s income and expenses (and savings), and a third that shows a timeline visualization of their major goals. Nonetheless, the key distinction of RightCapital’s Blueprint is its far more visual approach to showing clients their current financial situation, which is automatically updated over time via account aggregation.

For advisers who are fully invested in Asset-Map’s still more developed one-pager, RightCapital’s design likely isn’t enough to compel advisers to switch. Asset-Map has spent years iterating on its design and figuring out the best way to include so much information on a single page at the right level of abstraction without being overwhelming — which is no small feat — and RightCapital will likely need multiple iterations over time to fully catch up.

On the other hand, for advisers who might be interested in the approach and new ways to create more tangible visualizations and deliverables for clients — and don’t want to buy and pay for Asset-Map on top of their existing planning software — RightCapital’s Blueprint will likely be appealing as a way to better engage clients with their financial health over time, especially given the uptake of other more visual offerings, like One-Page Financial Plans which RightCapital also released recently with its Snapshot solution.

From the broader industry perspective, the significance of RightCapital’s Snapshot launch is that it highlights the challenges of startups that offer a key component of the financial planning process that’s still separate from the financial planning software itself. In the end, planning-centric advisers — who care the most about such features — still typically anchor first and foremost around their planning software, and don’t like to have to deal with double data entry. This means most will tend to use an embedded solution over other stand-alone offerings unless the external one is so much better it’s worth the extra work and extra cost.

This will raise the question of whether Asset-Map needs to become an even more full-fledged planning software to retain its market share and keep growing, especially if MoneyGuide and/or eMoney mimic RightCapital with their own one-page, mind-map-style visualizations. (A path that Asset-Map already has a foundation for with its ‘Target Maps’ to illustrate funding progress toward key financial planning goals, and extended in 2019 with more detailed cash flow projections of those target goals.) Or alternatively, whether another financial planning software company will look to acquire Asset-Map to jump-start its own capabilities in one-page visualizations (especially since Asset-Map has shown there’s a market of advisers who will pay for this, on top of their core planning software, as an ongoing tool for client/advice engagement).

At the same time, though, RightCapital launching an Asset-Map-style visualization (and the possibility that another planning tool would acquire Asset-Map to catch up) also highlights how a lot of innovation in financial planning software is not actually happening within existing planning software platforms, but in new startups growing around the periphery. Planning software will increasingly have to make decisions about whether to buy or build their own version of increasingly popular features from startups, as planning software itself increasingly becomes a hub that advisers anchor to. Though in the end, it may ultimately be welcome news to many AdviserTech startups to know that in the future, financial planning software providers may become the new exit-plan acquirers.

The typical financial planning client has a lot of complexity. In part, this is because the fees that financial planners charge are usually high enough that a client needs to have some nontrivial financial complexity just to have enough at stake to make it worthwhile to hire a financial adviser. And in part, it’s because if the situation wasn’t that complex, the client would likely just figure out or look up the answer themselves on the internet.

Because of the complexity of most financial planning problems, along with the fact that they tend to play out over years (or more often, decades), over which most people cannot intuitively do compounding math in their heads, financial planning software evolved relatively sophisticated capabilities to model complex planning situations, enabling advisers to conduct the appropriate analyses to craft the right recommendations.

The challenge, however, is that complex situations take a lot of time to analyze even with highly capable software. As a result, financial advisers typically only update clients’ financial plans once every several years (or only when an actual need arises). This means clients have little means to keep track of how they’re doing until their situation merits a full plan update.

A decade ago, Carl Richards made the case that everything that really matters to a client’s financial situation could be consolidated down to a single page: the one-page financial plan, or OPFP. It would capture the client’s values (or as Carl puts it, their statement of financial purpose) and goals, their current financial situation, and the action steps recommended to them to take next. Because in the end, when clients are “freaking out” about scary markets, that’s what we as advisers try to bring them back to anyway.

In September, Elements announced the launch of its own version of a one-page financial plan, designed in collaboration with Carl Richards, to cover the same core elements — purpose, goals, action steps and reporting on the client’s financial health (net worth, income/expenses, and a scorecard of their key household financial metrics).

Notably, the purpose of Elements’ OPFP is not necessarily to replace the traditional financial plan, or even to be part of the traditional initial financial planning process, but to serve as a monitoring tool for the ongoing client to see how they’re doing over time, with a continuously updated-by-software reporting of their financial health and key metrics (while also being reminded of their purpose and goals that have not changed).

From the adviser perspective, Elements and its OPFP are appealing because of the focus on monitoring and its ability to fill a void in providing meaningful engagement for ongoing clients around their financial plan. Elements was purpose-built for ongoing engagement, with a mobile-first design approach to its interface and visualizations and financial tracking for clients. This is arguably relevant both as a means to engage (and retain) existing clients, and also for marketing to prospects (where the prospect may be invited to set up their financial dashboard to monitor their situation as a “freemium” offer, akin to how Personal Capital built its lead generation funnel from its personal financial management app).

On the other hand, like other value-add tools in financial planning, Elements may find it difficult to get advisers to adopt it as a client engagement tool on top of their existing financial planning software. That’s in contrast with RightCapital, which recently launched its own OPFP module called Snapshot, which is embedded within the existing planning software, or eMoney, which already has a rather robust, albeit not perfectly OPFP, financial dashboard for clients. Though Elements’ use in prospect marketing may stand on its own, since in practice, most advisers aren’t using their financial planning software with prospects who typically haven’t gone through the full financial planning process yet anyway.

The key point is simply that when it comes to ongoing engagement — with clients, or with prospects — the full financial plan is overkill. It’s time-consuming to produce, so much so that advisers typically don’t update it more often than every few years. Additionally, long-term retirement projections don’t change much from year to year anyway. Whereas financial monitoring of key nearer-term financial metrics — savings rate or spending rate, tax rates, — can be more engaging on an ongoing basis. But such monitoring and engagement tools require a completely different kind of interface and client experience than traditional planning software. This is exactly where Elements and its OPFP are focused.

In the long term, though, the real question will simply be whether advisers are willing to pay separately for a one-page financial plan solution and ongoing financial monitoring tools like Elements, or if they will simply wait for their own planning software to offer it or to acquire Elements to offer it for them.

In the meantime, we’ve rolled out a beta version of our new AdviserTech Directory, along with making updates to the latest version of our Financial AdviserTech Solutions Map with several new companies including highlights of the Category Newcomers in each area to highlight new fintech innovation.

So what do you think? Will RIAs really increase their adoption of annuities if more favorably priced fee-based offerings are rolled out through DPL? Will values-based investing via direct indexing gain traction? As an adviser, would you use third-party client visualization tools if they added value to the client engagement, or do you expect, and wait for, your financial planning software to build and provide them?

Michael Kitces is the head of planning strategy at Buckingham Strategic Partners, co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay and fpPathfinder, and publisher of the continuing education blog for financial planners, Nerd’sEye View. You can follow him on Twitter @MichaelKitces.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound