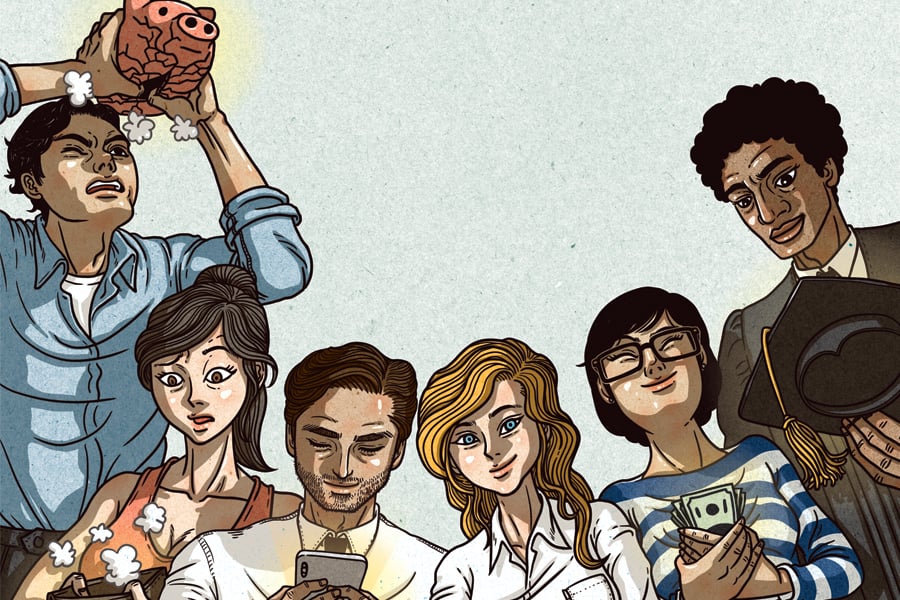

Financial advisers, like society at large, get an awful lot wrong about millennials — that group of 20- and 30-somethings who are an obsessive focus of generational discussion.

To a certain extent, it's not entirely advisers' fault. Seemingly endless articles spout broad and often negative generalizations about this large demographic: They are lazy, technology-dependent, disloyal, avocado-eating, participation-trophy junkies. The number of things they've supposedly "killed" are infinite and diverse. Don't expect to have lunch, a vacation, relationships, napkins, bar soap, mayonnaise, fabric softener, sex or even America itself in a future run by them.

"The word 'millennial' is constantly being spun as something negative," said Douglas Boneparth, a millennial financial adviser who works with young clients.

(More: The most outrageous things millennials are accused of killing)

But advisers stand to benefit greatly from better understanding millennials, also known as Generation Y. This group is expected to overtake baby boomers as the largest living adult population in 2019, according to the Pew Research Center, positioning them as advisers' largest pool of potential clients. Advisers could also raise the value of their practices by reducing average client age.

We set out to identify — and debunk — several harmful myths about millennials that may dissuade advisers from courting and landing this important customer base.

The criticisms in this category are numerous. Common refrains are that millennials don't have money, they don't have financially complex lives and they can't be profitable clients.

"So many advisers say that there isn't enough complexity in a millennial's life to require ongoing support," said Eric Roberge, founder of Beyond Your Hammock. "What they are really saying is that they don't know how to provide financial planning to millennials and, even if they did, they don't know how to get paid on it."

Millennials — individuals born between 1981 and 1996, according to Pew Research — have plenty of financial complexity. Planning opportunities are ample, said Mr. Roberge, including: managing cash flow and debt, buying homes, merging finances with a spouse, affording childcare, balancing saving for college with investing for retirement, and starting a business.

"Student loans is a major one," and the planning can be as complicated as it is around claiming Social Security, Mr. Roberge said.

Millennials have a mountain of student-loan debt, largely due to the rising cost of education and the fact that this generation is more educated than any prior group. Those with high student debt ($50,000+) consider full repayment their No. 1 financial goal, according to a

joint survey conducted by the CFA Institute and Financial Industry Regulatory Authority Inc.

Pricing for services geared toward helping clients manage student debt is possible, but won't fit into a traditional assets-under-management fee. The onus of figuring this out is on the adviser. Some advisers who serve young clients find that the cohort is willing to pay an annual or monthly retainer. Ian Bloom, owner of Open World Financial Life Planning, charges clients $200 a month for ongoing advice, for example.

But for advisers fixed to an AUM pay structure, there's also value in busting the myth that millennials aren't wealthy and therefore not worth their time. This isn't an entirely accurate depiction — the oldest millennials turned 37 this year, old enough to be making hefty incomes and to look into investing. Mr. Boneparth, president of Bone Fide Wealth, has a young, professional client base with salaries ranging from $400,000 to $1.2 million a year, for example.

Many millennials' ideas about money and the economy are tinted by the 2008 financial crisis. Either their early careers coincided with the stock market meltdown or they witnessed their parents' financial struggles firsthand.

The White House Council of Economic Advisers acknowledged in

a 2014 report about millennials that such economic conditions could affect millennials' financial behavior and beliefs about success — after all, those who lived through the Great Depression invested less, and more conservatively.

Some research seems to bear out this theory.

A recent survey from Bankrate.com found that cash is millennials' favorite long-term investment, while older generations prefer the stock market.

A Vanguard Group report published in June also found millennials who started investing with the fund company after the global financial crisis were twice as likely to have zero-equity portfolios as those who started investing before the crisis.

However, financial advisers see this research in a different light.

"If anything, they're not afraid of the stock market, they're just more aware of how much risk truly exists when you're investing in the stock market," said Rob Stromberg, a millennial and head of Mountain River Financial.

The Vanguard study found that the typical millennial household in fact takes "substantial" equity risk, allocating 90% of assets to equity markets. So, rather than showing an unwillingness to invest, millennials just need some education, advisers said.

"They need help to understand the market can go down but won't necessarily drop off a cliff every time," Mr. Roberge said. "And if it does. that's a huge buying opportunity for them … they have [a long] time horizon."

Millennials stand out for their use of technology: More than nine in 10 have smartphones and 85% use social media, edging out Generation X by a few percentage points and handily beating baby boomers and the silent generation, according to

Pew Research data.

Maybe that's to be expected from the generation that grew up during the ascent of the internet. However, it doesn't mean that all millennials want financial advice from an automated investment platform, or a so-called robo-adviser.

In fact, only 3% of millennials have used a robo-adviser, and only 16% expressed a strong interest in using one, according to the joint Finra-CFA study. Nearly 60% of millennials prefer working with a financial adviser face-to-face, the study said.

"To me that's fascinating, especially since millennials are digital natives and I know there's a lot of trust in technology," Gerri Walsh, senior vice president of investor education at Finra, said in a recent Finra podcast called "

Debunked: 7 myths about millennials — the underinvested generation." Said Ms. Walsh, "They want that human interaction."

Advisers prospecting for millennial clients who tout their technology or emphasize an easy relationship because of it will likely fall flat, Mr. Bloom said. Other advisers agree.

"I think most millennials are tech-savvy to a degree," said Matthew Fizell, a millennial-aged adviser at Irvine Wealth Planning Strategies who also serves millennial clients. "But just because you integrate tech into your practice doesn't mean millennials want to use it."

It may not be a surprise that the so-called "Me Me Me Generation," broadly seen as an entitled group that is loose with money, is viewed as a cohort of poor savers with bad financial habits.

That may lead advisers to ignore millennial clients, because "financial planning is strategic, you need to have discipline and nothing happens overnight," said Reshell Smith, an adviser at Ames Financial Solutions.

As it turns out, millennial money habits are actually similar to those of older generations, according to

a recent Bank of America report. Sixty-three percent of millennials are saving and 54% are budgeting — equivalent to Generation X and only slightly below baby boomers, according to the study. Over 70% of millennials with a budget stick to it.

Millennials also haven't exhibited out-of-control spending patterns. In 2017, 25- to 34-year-olds spent an average 8.6% of their after-tax income on items that could be deemed "frivolous" (entertainment, apparel and alcohol), according to Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey data. That percentage was in line with and even bested some older age groups, evidence that millennials aren't carelessly throwing away their cash.

Given the oodles of attention-grabbing headlines about millennials and retirement saving, advisers could be forgiven for thinking millennials hate the topic of retirement as much as they do American cheese. A recent piece from the National Institute on Retirement Security claimed 95% of millennials are

not saving adequately for retirement.

In fact, millennials seem willing to save for retirement, and in some cases are even doing better than older generations.

According to a

Transamerica Retirement Solutions report, 71% of millennials are already saving for retirement in an employer-sponsored retirement plan and/or outside the workplace. And millennial savers started at a median age of 24, which is younger than other generations: age 30 for Generation X and 35 for boomers.

Furthermore, a greater share of millennials contribute 10% or more of their annual salary to a workplace retirement plan: 39% for millennials compared to 36% for boomers and 30% for Gen X, according to Transamerica.

It's true that millennials show lower participation rates in workplace retirement plans than older generations, but that's

primarily a function of access to 401(k)-type plans (which increases with age) and ineligibility to participate, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts, rather than straight-up apathy.

"To be clear, as a whole, no generation is saving or has saved as much as it should," said Samuel Deane, financial planner at Deane Financial Partners Inc. "In fact, millennials are similar to their parents and grandparents when they were the same age, under new circumstances."

Advisers also acknowledge that millennials are in a different stage of life that pulls their financial priorities in several directions — from paying down student debt to buying a house, to name a couple. Millennials can be forgiven for putting off retirement saving, in some cases.

"The fallacy for advisers [is believing] everything is linear, and millennials need to save consistently throughout life," Mr. Roberge said. "As long as people are aware they're not maxing out their savings potential now and will have to do more of that in the future, you can create a plan that balances for today and saving for tomorrow."

Society perceives millennials — or really any generation — as a single, homogeneous unit. But millennials, the largest generation at 75 million people, also happen to be the most diverse group in U.S. history, according to

a 2018 report by the Brookings Institution, which pegs them at 44% minority.

Many millennials are immigrants or the children of immigrants who arrived in the United States as part of a surge in immigration that began in the 1940s, according to the White House Council of Economic Advisers.

"Millennials aren't a monolithic group," said Ms. Walsh of Finra. "Not only is this generation destined to be literally the most diverse in terms of ethnicity and racial identification, we see they have different needs."

African-American and Hispanic millennials, for example, are much more likely than white and Asian millennials to be noninvestors: 52% and 51% versus 42% and 38%, respectively, according to the Finra-CFA millennial study.

Advisers who approach all millennial clients with a generic touch will likely stumble, experts said.

"There's very little way to build something that helps all millennials," Mr. Bloom said. "While there are some unique concerns millennials will have — higher student-loan debt, maybe less financial acumen than other generations — those traits exist but will be wildly different person to person."

Advisers should become aware of any stereotypes or biases they may have formed about this important next generation of clients and colleagues, and begin to look at the person sitting across from them with fresh eyes for the potential they truly hold.