The latest round of budgetary brinksmanship recalls a similar government flirtation with financial calamity

The U.S. is quickly approaching a “fiscal cliff,” a combination of scheduled tax increases and automatic spending cuts that could seriously disrupt the economy. It's a grim situation, but not an unprecedented one.

The country has tottered on the edge of a similar budgetary precipice before -- and barely averted a national calamity.

At the heart of the earlier problem was disagreement between northern and southern states over tariffs on a wide array of manufactured goods imported from Europe. Tariffs were increased sharply after the War of 1812, pleasing the infant industries of northern states. But southern states, slowly realizing that there would be little benefit for them from protectionist policies, became restless.

Matters came to a head in 1832, when South Carolina attempted to nullify federal tariffs. President Andrew Jackson threatened to use force against the state if it persisted in its policy, and in 1833 Congress proffered an olive branch, as well: a promise to southern states that in 10 years, federal tariffs would be reduced substantially. The target date for reductions was fixed in law: June 30, 1842.

Deep Depression

Then events intervened. A speculative boom ended suddenly in the late 1830s, causing a major financial crisis. By 1840, the country was sliding into a deep depression. Northern workers and manufacturers were pleading for the continuation of high tariffs. And the Treasury, once flush with revenue, was empty.

Nor was the federal government able to borrow its way out of trouble. By 1842, one-third of state governments had defaulted on foreign loans, and European creditors were outraged. Leading bankers in London refused to lend the federal government a penny. “Let us get rid of that blasted country,” said Anthony de Rothschild, an influential financier. “It is the most blasted and the most stinking country in the world.”

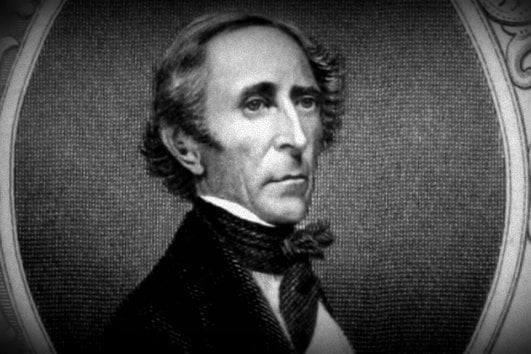

By the end of 1841, it was clear that the tariff bargain struck a decade earlier couldn't be kept. Yet Congress couldn't agree on a replacement. President John Tyler, sympathetic to the South, urged moderation on a new tariff policy. But northerners in Congress were in no mood for conciliation. Twice in 1842, Tyler vetoed bills that preserved high tariffs.

The mood in Washington was toxic. Months earlier, Tyler had also vetoed two bills to overhaul federal banking legislation. Almost all of Tyler's Cabinet had resigned in protest. Now, some in Congress were threatening to impeach him. One newspaper asked whether legislators “can really possess American hearts -- there being, apparently, so total an indifference to the interests of the country.”

One of the bewildered observers of the Washington scene was Charles Dickens, who arrived in the capital in March 1842. Tyler looked “worn and anxious,” Dickens wrote in his diary. “And well he might, being at war with everybody.” Another British correspondent wrote that “The condition of the country is most appalling ... The Treasury is bankrupt to all intents and purposes.”

By August 1842, Tyler and Congress had patched together a deal. The bargain struck between North and South a decade earlier was abandoned. The tariff wall was preserved, but the taxes on imported goods were lower than many northerners would have liked. Still, many northern manufacturers were pleased: The new law, one wrote, “is doing wonders for us.”

'Belligerent Parties'

Despite the deal, some southerners still seethed. The tariff bargain of 1833 had been “a treaty, made between belligerent parties,” said South Carolina Governor James Hammond. And now it had been broken. Some southern politicians once again called for secession.

Southern frustrations were somewhat relieved in 1845, when a new administration led by President James K. Polk lowered some of the tariffs that had been continued in the law of 1842. But this also cut government revenue. At the same time, Polk launched a war with Mexico, a conflict that proved to be much more expensive than promised. The combination of tax cuts and increased military spending plunged the federal budget back into deficit.

This time, however, European lenders were ready to help. The travails of the U.S. were negligible compared with the violence that was spreading across Western Europe. As the Rothschilds' American agent said privately, at least the U.S. wasn't “subject to the revolutions, the growing radicalism of Europe.”

And so the money flowed west across the Atlantic once again. The House of Rothschild became the biggest single subscriber to the Polk administration's war bonds, and the U.S. stepped back, for the moment, from the fiscal precipice

--Bloomberg News--

(Alasdair Roberts is the Rappaport professor of law and public policy at Suffolk University Law School in Boston and the author of “America's First Great Depression,” published by Cornell University Press. The opinions expressed are his own.)