Wealthy Americans, who were girding for the biggest set of tax increases in three decades just a year ago, now look mostly safe from higher levies for years to come.

But there’s one big, glaring exception: investment fund managers. If Democrats succeed in passing Wednesday’s surprise fiscal deal between Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, the carried interest tax break will end — eliminating a benefit used by private equity and hedge fund managers.

Only a few items from President Joe Biden’s set of ambitious, wide-ranging tax increases are still alive in the Senate. In the 50-50 chamber, Manchin has made clear he’s only willing to proceed with three tax measures: ending carried interest, increasing Internal Revenue Service audits on businesses and wealthy households, and imposing a 15% minimum levy on corporate profits.

The American Investment Council, which represents the private equity industry in Washington, immediately attacked the plan.

“Over 74% of private equity investment went to small businesses last year,” Drew Maloney, the group’s president, said in a statement. “As small business owners face rising costs and our economy faces serious headwinds, Washington should not move forward with a new tax on the private capital that is helping local employers survive and grow.”

The proposal to single out carried interest as the sole tax increase on high earners is rooted in Democrats’ longstanding disdain for a tax preference that lets fund managers pay much lower capital gains rates on much of their income. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, an Arizona Democrat whose vote is also crucial to the plan’s passage, has in the past declined to support ending that tax break. A spokeswoman for Sinema said she has yet to make a decision on the proposal.

Most rich Americans can largely thank inflation for allowing them to escape bigger payments to the IRS. Manchin has tied his opposition to tax increases on most individuals and small business profits to the surge in consumer prices, which he has argued could be worsened by Biden’s long-term economic plan. At the same time, Republicans are using inflation as a key theme in their midterm election campaign, which could see them take control of Congress, removing the possibility of more expansive tax hikes.

“There is clearly a sense of relief from most people who are earning near or over the thresholds proposed in the various tax plans,” said Ken Eyler, chief executive officer at financial advising firm Aquilance.

The Manchin-Schumer bill falls short of many Democrats’ hopes after a 2020 campaign that featured tax-hike promises and produced unified control of the White House and Capitol Hill. Advocates of more progressive tax laws are set to keep up the fight, using proposed levies on billionaires and other measures as a messaging tool. But that’s far from where they thought they’d be.

“The American people understand that it is virtually insane that you have some billionaires in this country in a given year and large multinational corporations that make billions of profits paying zero in federal taxes,” said Senate Budget Committee Chair Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent who caucuses with Democrats.

In the first months of his presidency, Biden proposed a sweeping list of tax increases that would kick in for individuals earning at least $400,000 a year, including:

Wealth managers quickly mobilized to advise their clients to realize gains, make adjustments to their estate plans and other tax-saving maneuvers before the end of 2021 — when Democrats were targeting the tax increases to begin.

Jack Ablin, the chief investment officer at Cresset Capital, said his firm was consumed with helping clients plan for changes.

But the political realities — and lobbying — slowly chipped away at the package as Democratic leaders sought to win lawmakers’ support. The increases were intended to finance sweeping large-scale investment in climate initiatives, education, child care and housing.

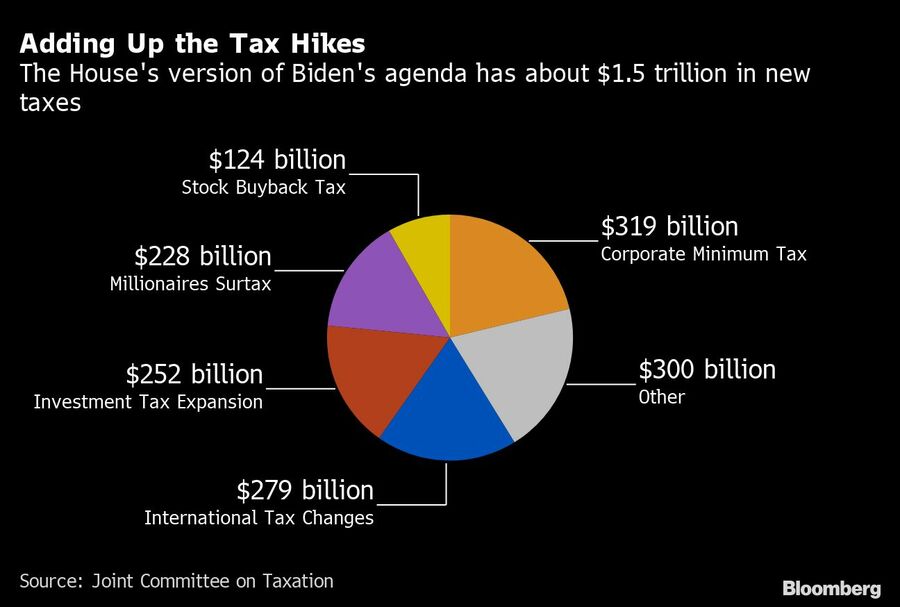

What was initially envisioned as a $3.5 trillion tax increase in spring 2021 shrank to roughly $2 trillion by last fall. When talks resumed this summer, Democrats were discussing a package with no more than $1 trillion in new taxes, with half of that going to new spending and half to reduce the deficit. The deal announced Wednesday has $451 billion in new taxes, plus $288 million in additional revenue from drug price savings.

Early in the negotiations some of most-feared proposals, including the changes to capital gains and step-up in basis, dropped out. Only more modest proposals to tax high earners and pass-through business income remained. Most Democrats see the Manchin deal as their only chance to pass any elements of Biden’s agenda.

The prospect of election losses this November aside, many Democrats are undeterred on pursuing a tax-the-rich strategy. They blame the failure to pass more of their tax plans on the select few moderates, and point to a solidification of support in their broader caucus for bolstering levies on the wealthy at a time of widening inequality.

Kim Clausing, a Treasury Department official until May, said she was surprised by how little disagreement there was within the Biden team over developing tax policies.

“I expected it to be somewhat more conflictual — that there might be different subsets of the administration with different tax policy priorities that we’d have to fight about,” Clausing said at a recent event. But “having these tight margins in Congress do make these things difficult.”

Ideas like taxing the wealthy and overhauling the investment taxation system were talked about chiefly in super-progressive circles a few years ago. But now they are ingrained in the mainstream of the Democratic Party — which progressives say is a win even if it doesn’t translate to immediate action.

“Democrats are now much more comfortable with taxes and seeing it as critical to their investment agenda,” said Frank Clemente, the executive director of the Americans for Tax Fairness, a group that advocates for higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations.

Reps. Don Beyer of Virginia and Steve Cohen of Tennessee just this week introduced legislation that would tax the unrealized gains of billionaires, following a Biden proposal from earlier this year.

That kind of continuing pressure leaves tax advisers wary about declaring a final victory over potential increases.

“Folks know that no impactful federal tax changes are likely for the next several years given the likely gains for Republicans in the midterms,” Aquilance’s Eyler said. But “if somehow the Democrats expand their Senate lead and keep the House, look for a mad scramble between Election Day and the end of the year” by the wealthy to prepare, he said.

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound