A newly elected president promising to tackle racial injustice and build a better and fairer economy and society. A Federal Reserve chairman who’d voiced satisfaction with the course of monetary policy the previous year. A sharply accelerating economy with an inflation rate that’s been below 2% for years.

2021? No, 1965, a year that marked the start of a years-long climb in inflation to double-digit levels the following decade. That’s an upward trend that some experts fear could be about to begin today, as a supercharged federal budget combines with a lax monetary posture to once again overheat the economy.

“If we do not have a recession that exerts disinflation, the odds are better than even that inflation will exceed 3% over the next five years,” former Treasury Secretary and paid Bloomberg contributor Lawrence Summers said. “They’re one in four that we will have at least a year of inflation above 5%.”

A marked speed-up in inflation -- it’s averaged just 1.5% over the past 10 years based on the Fed’s favorite measure -- would damage the U.S. economy, robbing consumers of the buying power needed to keep growth going. It would also undercut buoyant financial markets by putting upward pressure on interest rates.

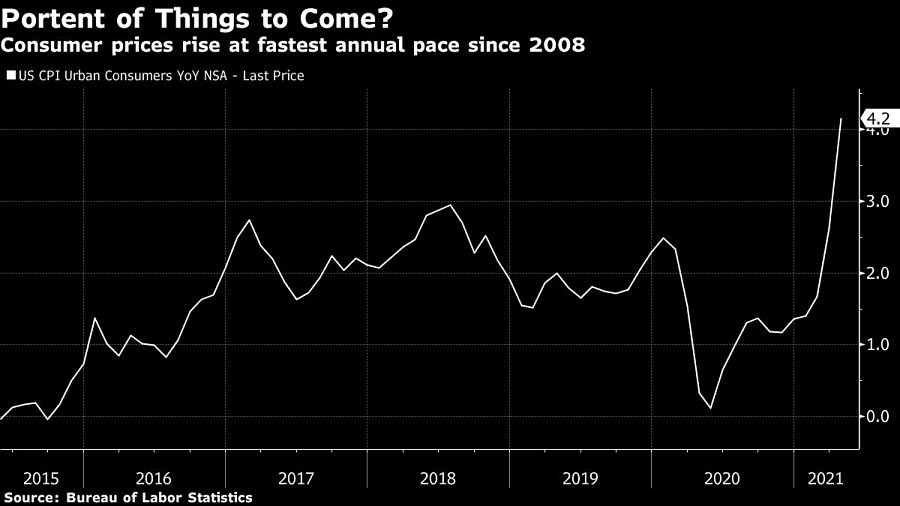

Investors got a hint of what might be in store last week, with the news that consumer prices jumped 0.8% in April alone. While some increase had been expected, the size of the run-up surprised forecasters inside and outside the Fed, raising fresh questions about consensus projections that inflation will ebb after a temporary rise on the back of a reopening of the economy.

Minutes of the Fed’s April 27-28 policy meeting will be released at 2 p.m. Washington time and could shed more light on the internal debate over price pressures and potential overheating.

“I’m fairly relaxed but not as relaxed as I was,” said Alan Blinder, former Fed vice chairman and a professor at Princeton University. “I’m moving a bit in the more alarmed direction, but not to the Summers camp.”

The argument of those who worry about a rerun of the 1960s rests with the simple law of supply and demand.

Just as then-President Lyndon Baines Johnson did in 1965 with his Great Society spending programs, current commander in chief Joe Biden wants to use the federal budget to reshape America. He’s already won congressional approval of a $1.9 trillion package and is seeking some $4 trillion more for an economy that is already booming coming out of the pandemic.

Some economists also see disturbing parallels in Fed policy between now and then. They worry that the Fed’s new strategic framework -- it’s openly seeking higher inflation -- risks letting price increases get out of control, just as occurred in the 1960s.

While then-Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin had a nasty confrontation with Johnson at the end of 1965 after the central bank raised interest rates, economists generally fault him for not acting more forcefully to restrain a rise in inflation to 4.9% at the start of 1970.

The risk is that a potent mix of super-loose fiscal and monetary policies will again end up straining the economy’s capacity to produce enough supply to keep up with the elevated demand, leading to widespread price increases.

“History doesn’t necessarily have to repeat, but the fact that it happened before does mean it can happen again,” said Peter Hooper, global head of economic research for Deutsche Bank.

He sees at least a one-in-five possibility of inflation rising to 3% or more over the next few years, markedly above the average 2% target that Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues adopted last year.

Powell has pushed back on concerns that the central bank will repeat its inflationary mistakes.

“We’re all very familiar, at the Fed, with the history of the 1960s and '70s,” he told reporters April 28 after the central bank reaffirmed its ultra-easy policy of near zero interest rates and massive bond purchases. “We know that our job is to achieve 2% inflation over time.”

White House officials also have played down worries about overheating and have portrayed the administration’s push for more spending as long-term investments rather than short-term boosts to demand. But they’ve made clear that it’s the politically independent Fed’s job to make sure price hikes don’t run amuck.

Powell is betting that structural forces that became ingrained in the economy after the inflationary 1970s will help limit price pressures as growth takes off.

“We think that the inflation dynamics that we’ve seen around the world for a quarter of a century are essentially intact,” he told lawmakers in March. “The U.S. has had low inflation for some time, and we think those dynamics haven’t gone away.”

Those dynamics include increased globalization and the cheaper-priced imports it brings, waning worker bargaining power and well-anchored inflation expectations. If inflation is seen as staying subdued, that can act as a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy: Workers don’t feel compelled to press for outsized wage increases while companies are more inclined to cut costs than raise prices.

Summers said he’s “very concerned” about the inflation outlook and suggested that the Fed’s faith in well-moored expectations may end up misplaced.

“I can’t understand how they can say that this is the biggest policy revolution in 45 years since the Great Society and the Fed is having the most radical change in its operating model in a generation, but we know from experience that expectations are anchored,” he said.

While he doesn’t see anything like the economic overheating Summers fears, Blinder said he wouldn’t be surprised if inflation rises too high for the Fed’s liking sometime in the next few years. That could prompt a reaction from the central bank that inadvertently tips the economy into what is a “hopefully mild” recession.

“The Summers view -- which you can summarize as saying there is a hell of a lot of aggregate demand pushing on less aggregate supply -- is not completely wrong,” Blinder said. “There is a point there.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound