IBM made waves in the retirement plan world last month when the company revealed that it’s going back to a defined-benefit pension of sorts in lieu of contributing to employees’ 401(k) accounts.

At the beginning of 2024, the 5% match the company currently provides within the 401(k) plan will instead go to what it calls the Retirement Benefit Account – a portable account with a fixed rate of return over three years that appears to be a cash balance plan.

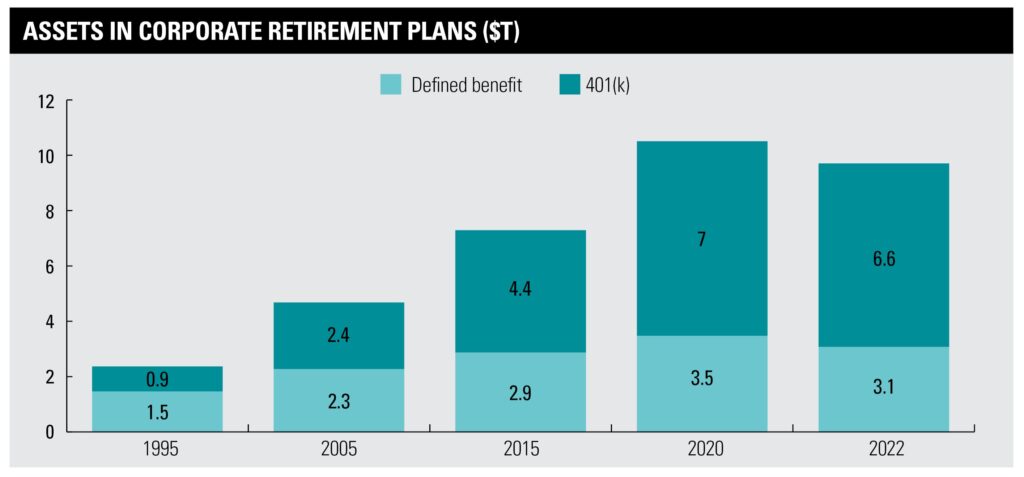

That on its own would be newsworthy, as the trend in corporate retirement benefits has been to shift the risk of saving and managing investments for retirement to workers through the use of defined-contribution plans.

But how the news sits with other recent events is even more unusual, raising interesting questions about whether there is a future for defined-benefit plans in the corporate world.

IBM’s change coincides with many other big employers offloading their pension liabilities to insurance companies, in a move known as a pension risk transfer, as interest rates have buoyed the plans and made them positively funded for the first time in a while. And some businesses that years ago rid their books of pension plans have recently rebuffed demands from workers to have pensions reinstated. The United Auto Workers, for example, was unsuccessful in getting the big three automakers to bring back defined-benefit plans, instead getting the companies to agree to higher employer contributions to 401(k)s.

In IBM’s case, there has been speculation that the change was simply in the company’s financial interests, in part because the 1% automatic 401(k) contribution the company made in addition to the 5% match is going away, reportedly replaced by a one-time salary increase.

But people who are steeped in retirement-plan-design research and consulting see it differently.

“It’s very possible that a defined-benefit plan, such as IBM’s, could be cheaper than a very, very generous DC plan. But according to my research, for over 25 years employers have switched to a DC model because it was 5% to 15% cheaper per person,” labor economist Teresa Ghilarducci said in an email.

Unlike DC plans, participation in DB plans is mandatory for workers whose employers provide them, she noted. “DB plans get a higher rate of return per dollar contributed. DB plans are a lot more efficiently run. And the direct cost of administration does not fall to the employee.”

Some employers opt to pay for 401(k) plan administration, but often workers help pay, or fully pay, those costs, which can be assessed through account charges or via fees tacked on to the mutual funds within the plan.

And defined-contribution plans can weigh less heavily on public companies’ balance sheets, which has been an incentive for employers to switch, said Jamie McInnes, president of Oculus Partners.

“The issue with [DB plans] is that as people have been living longer, those liabilities have been getting more expensive,” McInnes said. “You end up with a liability that translates, frankly, to your income statement. It impacts your earnings.”

A poorly managed 401(k) might be bad for workers, but a poorly managed defined-benefit plan is also bad for the company, said Don Trone, CEO of 3ethos, a firm that researches and consults on leadership, stewardship, and governance.

“Underfunded pension plans have to be reported in the balance sheet,” Trone said.

It’s hardly surprising that the United Auto Workers couldn’t get Ford, GM, and Stellantis to bring back defined-benefit programs. Restoring those pension plans was a key demand in the recently resolved strikes. U.S. automakers not only froze pension plans years ago, but more recently they’ve transferred the liabilities they once had to insurance companies.

“Presumably, they were not interested in reinstating those liabilities,” McInnes said. “I would have been really surprised had the manufacturers agreed to reenter those arrangements.”

The government agency that insures company pensions, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., has seen three years of solvency, according to the annual report it issued Nov. 16. The PBGC’s multi employer program has had positive net assets, and will likely continue to for 40 years, as a result of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021’s Special Financial Assistance Program, which sought to prop up underfunded defined-benefit plans.

Defined-benefit plans, which used to be the norm, ran into trouble as life expectancy increased. Companies that provided the plans long ago didn’t assume that their workers would live decades beyond the once-common retirement age of 65. That made plans costlier to provide as employers had to put more money into funding them and pay increasingly high PBGC premiums, McInnes said.

However, the system IBM is switching to – a cash balance plan – is a hybrid program, with elements of defined benefit and defined contribution. The company has indicated that the assets it earmarks for workers are portable, meaning they can take them to other employer plans or individual retirement accounts via rollovers. For workers, portability has been one of the positive aspects of the widespread switch to 401(k)s.

“Most companies didn’t realize that when they made that shift from defined benefit to defined contribution, it was … putting greater demand on the company to show leadership and stewardship to the employees,” Trone said.

Surveys have shown that only about 25% of workers feel that their employers have their best interests in mind, he noted. And that sentiment has a strong effect on whether employees contribute to the company 401(k), he said.

“They just see [contributions] as the big boss taking a chunk out of my paycheck,” Trone said. “That’s one of the reasons why 401(k) plans as a general rule have been disappointing.”

Conversely, a defined-benefit plan, such as the one being introduced by IBM, is better for the average employee, “because the company is managing the retirement risk,” he said.

There are benefits to employers, not the least of which is that offering a traditional pension is seen as a recruiting tool. In IBM’s case, though, it’s worth noting that there has been opposition to the change, as employees have been petitioning the company to reinstate the 401(k) match and automatic contribution.

But additionally, a traditional pension scheme is thought to help employers manage the costs of their medical benefits, as defined-benefit plans encourage people to retire younger, when they typically have fewer health issues, Trone said. “It’s a question of whether a defined-benefit [or] cash-balance plan makes it easier for a company to control their health care costs, particularly with their elder employees.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound