Wealthy people currently enjoy what is likely their greatest opportunity in modern history to transfer assets to their children while being taxed as little as possible. But it’s a window that advisers say could be closing.

As a result, intrafamily loans, along with other methods of wealth transfer, are in high demand.

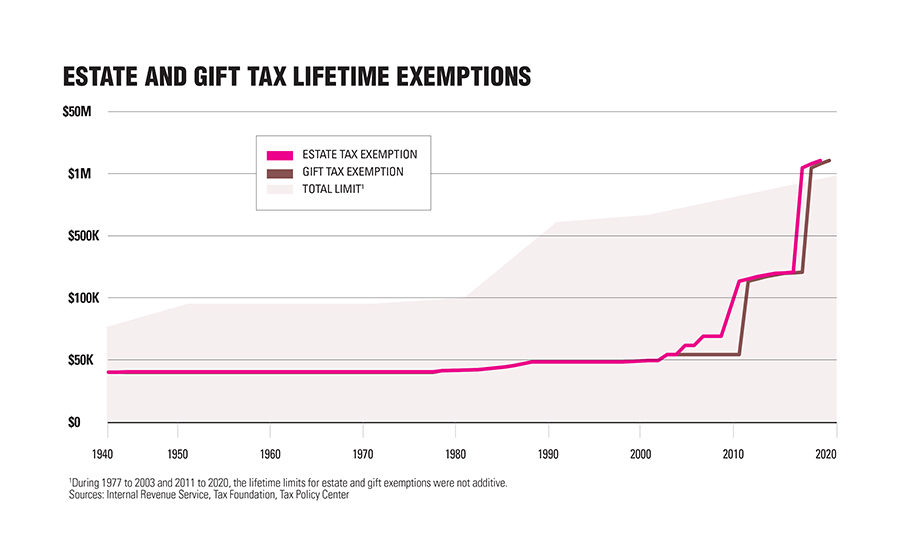

Tax rates could go up over the next few years, and interest rates are currently at record lows. Perhaps most importantly, especially for well-heeled clients, the current lifetime gift exemption of $11.58 million per person, and $23.16 million for a couple, is due to expire in 2026, and it could end sooner than that.

For business owners looking to transfer companies to their children, the current environment offers yet another advantage. “COVID has also created an opportunity for potentially lower business valuations,” Marianela Collado, CEO of Tobias Financial Advisors, wrote in an email. That provides a “perfect window of low interest rates and low valuations to get the biggest bang for your transferred ‘buck.’”

As of August, the applicable federal rates, or AFRs, published by the IRS that apply to intrafamily loans are 0.17% for short-term loans, 0.41% for mid-term loans and 1.12% for long-term loans.

In his recent economic and tax plan, presidential candidate and former Vice President Joe Biden did not specifically call out the lifetime gift tax exemption, which jumped as a result of the Trump tax cuts. But in an overview of his plan, Biden alluded to “reversing some of Trump’s tax cuts for corporations and imposing common-sense tax reforms that finally make sure the wealthiest Americans pay their fair share.” And a framework for his policy noted that “estate taxes should also be raised back to the historical norm.”

The tax reform enacted in 2017 dramatically boosted the lifetime gift tax exemption, nearly doubling it from the prior limit of $5.5 million for an individual.

“Most of our high-net-worth clients are concerned about the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act expiration and the possibility of a sea change in D.C. in November that causes an immediate change in the estate and income taxes,” Leon LaBrecque, chief growth officer at Sequoia Financial, wrote in an email. “[There] will be a big rush in estate planning on the high-net-worth, especially business owners.”

An intrafamily loan is one strategy for passing along wealth, especially for parents who want to help their adult children but cannot afford to gift a big chunk of their life savings.

For wealthier clients who have reached their lifetime gift exemptions, or are likely to, other strategies are being deployed, such as the grantor-retained annuity trust, or GRAT, or the intentionally defective grantor trust, or IDGT.

In a GRAT, “in its simplest fashion, the grantor is going to give funds to this trust, [and] they’re going to get their funds back,” said Rob Greenman, lead adviser and partner at Vista Capital Partners.

“It can be a great way to shift money, without using up your federal exemption, to the next generation,” he said. With a GRAT, “it’s like, heads, you win; tails, you don’t lose anything.”

With a GRAT, grantors receive annuitized payments, along with interest, from the funds they’ve deposited in the trust. Whatever money remains in the trust’s investments at the end of the term, if any, goes to the beneficiary, free of estate tax, Greenman said.

“We have a client [whose] net worth went up substantially due to a transaction, and suddenly they had a future estate tax liability,” he said. That client had sold a business, and they wanted to pass some wealth to a child without incurring estate tax, he said.

As an example, a grantor who funded a GRAT with a three-year term with $1 million would be paid back about $338,000 a year for the three years, using the IRS 7520 interest rate for July of 0.6%, Greenman wrote in an email. That interest rate is 120% of the midterm AFR, rounded up to the nearest two-tenths of a percent.

Assuming a 10% annual rate of return on the trust’s investments, the trust would hold about $200,000 at the end of the three years, all of which would go to the beneficiary. There would be no estate tax on that amount, which represents an $80,000 savings, assuming the top federal rate of 40%, Greenman noted.

The cost of the strategy is limited to the legal fees in establishing the trust, he said.

Business owners who want to pass their interest in the company to a family member have another option, the IDGT.

A business owner could set up an installment sale to an IDGT by first funding the trust with a gift, often 10% of the purchase price of the business, Greenman said. The owner then sells an interest in the business to the trust, which has a promissory note identifying the interest rate.

Assuming a business is worth $20 million and generates $2 million in annual profit, a 15-year-term IDGT with a 2% interest rate would require interest payments of $400,000 a year, Greenman cited as a hypothetical example. The trust would make a balloon payment of the remaining principal at the end of the term, and no capital gains taxes would be due, he noted.

“The nice thing about funding it with a private company is that because it is an illiquid asset, you can take a valuation discount on what you’re putting into this,” Greenman said. “As long as that business appreciates in value … any of that growth that occurs above the super-low AFR rate passes, free of estate tax.”

IDGTs allow a business to be sold to a trust at very low rates, especially in the current environment, LaBrecque said.

“In a case we are working on, we have a business [with] a minority stake that was worth about $13.3 million before the COVID [crisis], and is now is worth about $10 million,” he said. Taking a discount of 20% puts the value of the stake at $8 million, which is the amount for which it was sold to the trust. With a seed gift of $800,000 and a nine-year note with an interest rate of 0.41%, annual payments will be about $816,500, which are covered by the business’s cash flow, and total interest for the term will be $148,400, he said.

“At the end of nine years, the IDGT owns the business interest, which if it goes back to its original value and hangs onto the excess cash flow, is over $20 million,” LaBrecque said. “We [would have] moved $13.3 million of business interest … while using up only $800,000 of exemption.”

A variation on the IDGT is a spousal lifetime access trust, or SLAT, Nicole Hart, senior vice president of trusts and estates at Wealthspire Advisors, said in an email. That strategy, which was popular when the then-$5 million lifetime gift and estate tax exemption was set to expire in 2012, allows a spouse to be named as a beneficiary to the trust, Hart said.

Couples can establish SLATs for each other, though they cannot be identical in nature, she said.

For high-net-worth clients, the high current limit on lifetime gift tax exemptions is a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Hart said during an interview. “We’ve been encouraging clients to use up their exemptions to the extent they can.”

The limits set by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will expire in 2026, effectively being cut in half, though that could happen much sooner if Congress changes the law, she said.

Some clients have used up their full gift tax exemptions, making intrafamily loans or GRATs a good option for additional wealth transfer, Hart said.

“Now we’re striking while the iron is hot and reaching out to clients,” she said. “The interest rates right now are so low, which means that the hurdle rate for making the strategy successful is lower.”

The firm keeps track of clients with intrafamily loans and has contacted some who could benefit from refinancing, given the low rates, Hart noted.

With so much uncertainty right now, some clients are uncomfortable with making outright gifts to children, and loans can be more appealing, she said.

“Depending on what the goal is, you can see clients who are not very high-net-worth who are utilizing this strategy because they want to support their kids,” Hart said. “It’s more of an economic reality that ‘I’m able to do this, but I’m not able to fully give to my kids.’”

When clients initiate an intrafamily loan, it is crucial that they understand that it must be treated as a formal arrangement, she said. For example, interest must be paid by the borrower, and the loan can’t simply be forgiven, as there are big tax consequences for that.

“You have to follow the formalities to make sure it doesn’t look like a gift,” Hart said. “We are diligent about making sure clients understand that.”

There is also a risk to some families if repaying a loan becomes a problem, Collado said.

“I always caution that planning is great, but you can’t do it at the risk of jeopardizing your financial health,” she said. “I like strategies that provide a claw-back if needed.”

There are no rules on how small an amount a GRAT can be used to transfer, but the limiting factor is generally the cost of establishing the trust, Greenman said.

Grantors or lenders should ask whether the tax savings they can realize are worth the complexity of the wealth-transfer strategies, he said.

“You can do all sorts of creative planning, but a lot of the time, saying ‘no’ to these strategies is the right thing to do,” he said. “Some clients are comfortable paying a little bit of estate tax and don’t want to introduce complexity into their lives.”

Another consideration is the effect that lending can have adult children’s lifestyle expectations and views on money, Tara Unverzagt, founder of South Bay Financial Partners, said in an email.

“Borrowing from family members or the trust can be pretty traumatic,” Unverzagt said. “There is definitely an issue with some family members ‘trying to keep up’ with other family members.”

Relying on family money can inadvertently discourage children from saving on their own, and they can later end up having too little to support the lifestyles they’re accustomed to, she said.

It is important to “[teach] a new generation how to handle money appropriately,” she said. “Providing a ‘safety net’ [while] supporting a lifestyle that is higher than a child can support on their own, even with family money, in the long run doesn’t help anyone.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound