Entrepreneurs need to be rewarded for taking risks, not shackled

The U.S. is holding a debate that is critical to its future: whether to tax, redistribute and consume income that would otherwise be invested.

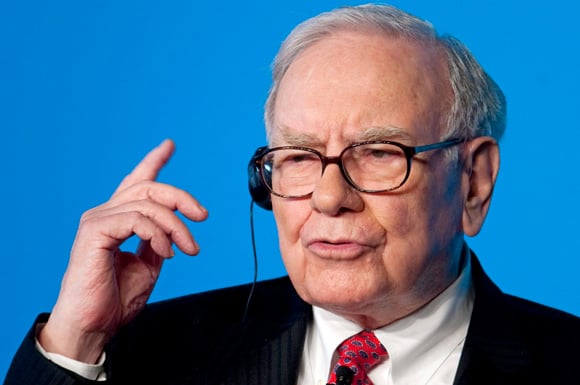

Warren Buffett has weighed in, supporting higher taxes on wealthy taxpayers. Unfortunately, the evidence he uses to make his case is superficial and flawed. One can't help but wonder: If he had stronger evidence, why wouldn't he use it?

Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., is an iconic leader. The U.S. needs insightful analysis from him. His claim that taxing upper-income taxpayers doesn't reduce investment runs counter to standard economic logic.

Federal Reserve surveys show the top 5 percent of households save and invest 40 percent of their income. Median- income households save very little, whereas the Buffett household probably invests 99 percent of its income.

If we tax, redistribute and consume income that otherwise would have been invested, the investable pool of savings declines. With a smaller pool of capital, less-attractive investment opportunities remain unfunded. Buffett tautologically claims investors will continue to invest in opportunities with expected returns above the cutoff point. Of course they will. Investment is lost at the margin.

Buffett points to the 1950s and 1960s, when marginal tax rates were higher, and claims that because the economy grew faster then, it can grow faster today with higher marginal tax rates.

Different Economies

What he fails to mention is that the advent of interstate highways and television knitted together the U.S economy in the 1950s. Large capital-intensive companies such as General Motors Co. (GM) and Procter & Gamble Co. raced to exploit previously unrealized economies of scale.

As a result, entrepreneurs and individual tax rates mattered much less to growth then than they do today. Growth accelerated independent of the tax rate.

The U.S. sent its workforce to college long before the rest of the world. That also opened new investment opportunities. Two decades of underinvestment in the private sector -- first during the Great Depression and then during World War II -- added further to the rebound. The cost of food dropped from more than 20 percent of gross domestic product to less than 10 percent, freeing resources to fuel the manufacturing boom.

A much smaller portion of GDP was taxed, redistributed and consumed. Federal, state and local government spending was 28 percent of GDP then versus close to 40 percent today. The 1950s and 1960s don't provide evidence that increased government consumption, and the taxes needed to fund it, has no effect on growth. They show that investment matters.

Buffett also claims the commercialization of the Internet in the early 1990s created a huge tailwind that benefited the rich, as if investors did little to earn this success. Similarly, proponents of higher taxes and spending often claim that faster growth in the 1990s demonstrated that higher taxes on investors don't hurt growth even though the commercialization of the Web would have accelerated growth independent of the tax rate.

Comparing the growth of the U.S. with Europe's since the early 1990s removes the effect of the Internet. Both economies had access to the same technology and similarly educated workforces to capitalize on the Web's opportunities. Since then, the U.S. economy has grown 63 percent (in the period through the end of 2010); France and Germany's together grew less than half as fast. U.S. productivity growth increased from 1.2 percent a year to 2 percent while France and Germany's declined to less than 1.5 percent a year in the periods 1972-1995 versus 1995-2004. Without U.S. innovation, Europe's growth would have been lower.

European Contrast

It is true that higher labor redeployment costs slowed Europe's transition away from manufacturing. Yet that doesn't explain why young, talented European workers clung to jobs in declining industries while their American counterparts eagerly walked away from promising careers to join risky startups.

In the U.S., higher payouts drove increased risk-taking. Success from that risk-taking raised the bar for success. The most promising U.S. students flocked to business schools and worked much longer hours than their underutilized counterparts in Europe, whose work effort declined. The success of these American workers created Google Inc., Facebook Inc. and countless other companies that gave the U.S. workforce more valuable on-the-job training. That training increased the chances for entrepreneurial success.

Entrepreneurial success put equity into the hands of investors willing to underwrite the risks that produce innovation. No surprise, the U.S. has more equity per dollar of GDP than Europe and Japan, and has produced more innovation. Although commercializing the Internet may have created a tailwind, a lot of that tailwind was earned.

Government spending was also much lower in the 1990s than it is today: 18 percent of GDP versus 24 percent. State and local government spending was lower, too. As a result, President Bill Clinton's across-the-board tax increase paid down debt, which strengthened the U.S. economy.

Today, higher taxes are needed to fund an increase in unproductive consumption, which slows growth. Taxing income that otherwise would have been invested as equity in order to retire cheap offshore debt seemed like bad economic policy in the 1990s. With 20-20 hindsight, however, it turned out to be an ideal time to sell overpriced equity to pay off debt. That's not the case today when equity is dear. Far from showing that tax rates and government spending have no effect of growth, the 1990s provide evidence that payoffs for risk-taking and the accumulation of equity matter.

The debate over whether to tax, redistribute and consume income that would otherwise be invested is critical to the future of America. The nation can't afford to base its decision on superficial arguments. The country deserves better from a leader such as Warren Buffett.

(Edward Conard was a partner at Bain Capital LLC from 1993 to 2007. He is the author of “Unintended Consequences: Why Everything You've Been Told About the Economy Is Wrong.” The opinions expressed are his own.)