It's easy to dismiss the Occupy Wall Street movement as a gathering of misguided, hopelessly idealistic brats who would rather whine about unemployment than pound the pavement in search of work. It's easy to deride them for their misspelled signs, rudderless intensity and attention-seeking antics, such as when a group of protesters in New York dressed as zombies eating Monopoly money.

But ignoring the movement would be a huge mistake.

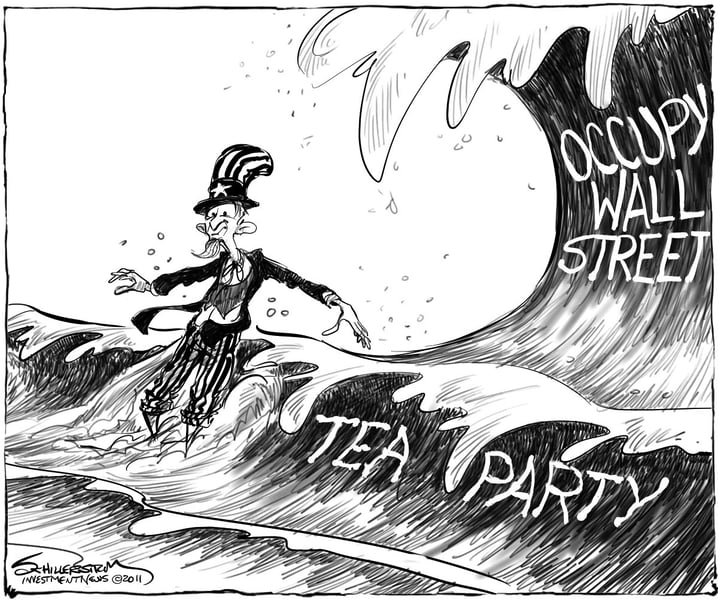

Like it or not, the Occupy Wall Street protests — which started a month ago as a gathering of a few hundred protesters in a little park in Lower Manhattan and has grown to include thousands across dozens of cities — is part of a growing populist wave that has the potential to upend the nation's political landscape.

Much as the out-of-nowhere Tea Party movement captured the public's attention and galvanized the Republican Party in the 2010 elections, the Occupy Wall Street movement — fast gaining momentum as a political force on the left — has the potential to rattle Democrats.

While both movements tap into the resentment and frustrations of great masses of Americans, the Occupy Wall Street movement may appeal to a wider demographic.

Tea Party supporters are mainly white, male, married, older than 45, more conservative than the general population and likely to be wealthier and better educated than the general population.

While it's still too early for a full demographic map of Occupy Wall Street protesters, the group appears to be more diverse in terms of race, education and socioeconomic status. For now, the protesters appear to be skewing on the younger side, but that is likely to change as they become more organized.

The big-picture messages of the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street are clear: Among the former, the consensus is that the government is too burdensome and intrusive; among the latter, the mood is that Wall Street and big business have their fingers on the scale and have tilted the economy to keep the bulk of its rewards.

In many ways, both camps are right. Yes, their tone and style may grate. And, yes, each side demonstrates some glaring philosophical inconsistencies.

Still, each group is onto something, shining light on matters that our political establishment has long ignored and still is ignoring.

For years, we've read about the government's purchases of $1,000 toilet seats and just laughed. We're now not rich enough to afford such profligacy, and taxpayers no longer are willing to put up with it.

Similarly, the economic recoveries that added no new jobs, coupled with the gutting of American manufacturing and a decline in median income, have produced a middle class that is losing ground. American income distribution is more unequal than at any time since the 1920s, and for the first time in our history, we believe that our children will be worse off than we are.

This serious blow to the American dream is not just a figment of the imagination of a group of neo-hippies in Lower Manhattan.

Whether it was abolition, women's suffrage or Prohibition and its subsequent repeal, mass popular movements in the U.S. start out on the fringe and — if they tap deep enough — go on to change American society as a whole.

Last week, in an article appearing on the Huffington Post website, Mohamed A. El-Erian, chief executive and co-chief investment officer of Pacific Investment Management Co. LLC, suggested that Occupy Wall Street is likely to become a serious social movement.

Rather than dismiss it as “noise,” he said that the media and politicians should “listen to it as a "signal' of the challenges America faces as a compassionate society, and as a democracy built on the importance of fairness and opportunity.”

He's right. Unlikely as it is that the Occupy Wall Street agenda (whatever that turns out to be) will be adopted wholesale by Congress, advisers can be sure that the group's intensive illumination of stratospheric executive compensation and bank bailouts will translate into a public mood more conducive to higher taxes on the wealthy.

And when moods shift, legislation follows.