When it comes to the value of financial advice businesses, RIAs have won the wealth management race and are outdistancing broker-dealers.

Valuations have skyrocketed at registered investment adviser firms, recently hitting never-before-seen levels, with bankers and executives whispering that a limited number of transactions have reached valuations of 18 times to — gasp! — 20 times a firm’s annual EBITDA, a cash-flow metric that stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

Take a firm with $1 billion in client assets. It could potentially generate $10 million annually in revenue and $3 million in EBITDA. That means it could see a potential bid of around $54 million based on a valuation of 18 times its EBITDA valuation, depending on the ardor of the buyer and how well the businesses fit.

Which begs the question: Where is the ceiling?

Indeed, there’s a touch of pixie dust that goes into RIA valuations at the moment, said Carolyn Armitage, the new head of Thrivent Advisor Network and until recently managing director at Echelon Partners, an investment bank and consultant to wealth management firms.

“Advisers advanced their businesses during Covid and have been attracting private equity buyers, who have invested in other industries, and are attracting a whole variety of acquirers,” Armitage said. “That only increases the competition.

“And private buyers don’t disclose details, meaning they can take a long-term approach to the business they are investing in,” she said. “Private equity funds are trying to get out of their investment in four to seven years, but the new buzzword is permanent capital, meaning a 10-year time horizon.”

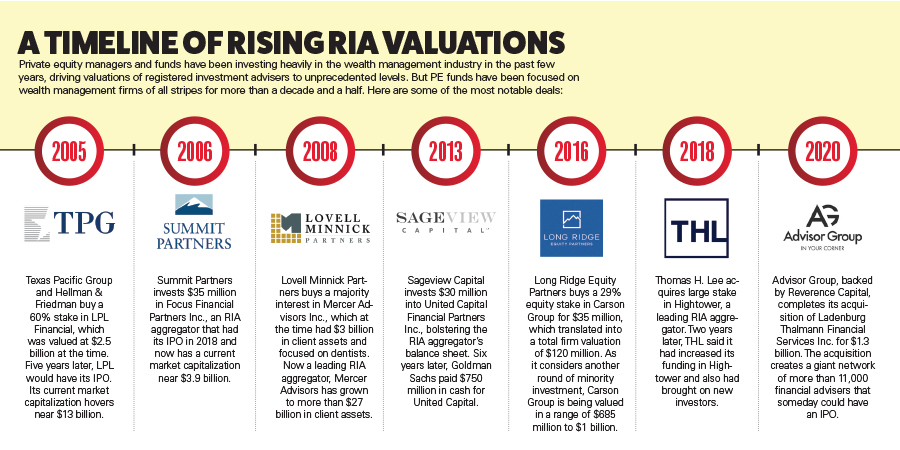

Private equity managers are in large part responsible for the surge in RIA valuations. There were 78 acquisitions last year of RIA firms with at least $1 billion in assets under management, according to Echelon Partners, the most in a single year.

In total, $318 billion in assets were acquired last year, and the average seller boasted $1.8 billion in assets under management. Compare that to 2010, when InvestmentNews reported a total of 70 deals involving assets of $62 billion.

And that current heady valuation level is double or even triple the typical valuation for RIAs a decade or so ago, right when private equity managers began to look to buy RIAs in earnest.

Broker-dealers are holding their own when it comes to the value of their businesses, particularly if they have a good chunk of client assets in advisory or fee-based accounts. But brokerage firms face clear shortcomings — most importantly, the rock-bottom level of short-term interest rates. Those severely crimp earnings from the cash sweep and margin accounts at broker-dealers.

Now giant broker-dealer branch offices, taking full advantage of the RIA craze, are turning themselves into RIAs.

That means some of the smartest, most successful brokers on Wall Street are backing away from their roots — generating revenue in sales and commissions — and placing their chips on the RIA market, which charges the client an annual fee, most commonly priced at 1% of a client’s assets.

The rise in RIA valuations is remarkable. Just five years ago, Carson Group had a total valuation of $120 million. Today the firm has $17.3 billion in client assets and its own homegrown technology, and InvestmentNews reported this month that Carson Group is being valued from $685 million to as much as $1 billion as it looks for capital to continue buying other wealth management firms.

Such a valuation would mean Carson Group — which was launched in 1983 by the colorful Ron Carson, and was a leading branch at LPL Financial for years — is now worth six to eight times more than it was in 2016, the first time it sold a minority stake.

Carson Group, of course, is one of the largest and most established RIAs in the industry, and not all firms have its pedigree. But the question is obvious: How high can RIA valuations go, and are they indicative of an out-of-control bidding war or more in line with the appropriate and long-term value of firms?

While some private equity managers and other potential buyers are leery of the all-time high in RIA prices, there is still room to run, albeit selectively, said Larry Roth, a consultant who has decades of experience in the wealth management and banking industries, including stints as CEO of AIG Advisor Group and Cetera Financial Group.

“The seller can earn over 20 times current EBITDA if the agreement provides an incentive for growing the business post-closing,” Roth said.

“Only somebody living in a cave on Mars over the past 10 years would believe RIA valuations have peaked or that we’re in a big M&A bubble that’s going to burst,” said Adam Malamed, CEO of Ajax Investment Partners, a private investment firm that focuses on venture capital and M&A advice.

“Buyers of successful RIA firms know that they are acquiring an asset that is extremely well-positioned to grow organically across a very wide range of potential scenarios over the next two decades,” said Malamed, the former chief operating officer for Ladenburg Thalmann Financial Services Inc. “There aren’t many businesses up for sale that offer a robust return simply for holding the asset, which is very much the case with RIA firms.”

A glance at the public market value for Focus Financial Partners Inc., LPL Financial Holdings Inc. and Morgan Stanley gives an indication of how highly valued RIAs are compared to brokerage firms.

The following data were culled from CNBC.com on June 3, back when shares of AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. were soaring and crashing. Using the same simple valuation formula to price RIAs — market capitalization divided by EBITDA — reveals the premium RIAs now command. Focus Financial was trading at 15 times EBITDA, LPL Financial 13.1 times, and Morgan Stanley 8.1 times.

The comparison isn’t perfect. LPL is making a push into the RIA custody business, and Morgan Stanley is also a global investment bank and trading platform and dwarfs Focus Financial and LPL in terms of market capitalization.

What’s also clear is that well-run RIAs are kicking off plenty of cash flow, making them highly attractive to buyers. Broker-dealers are also larger, often more complicated and heavily regulated enterprises whose revenue depends on transactions — a euphemism for sales, that dirty word in the wealth management industry.

And the broker-dealer industry is moving in the direction of fees.

InvestmentNews recently reported that for the first time since it began its survey of independent broker-dealers, the top 25 firms last year reported that fee revenue made up 50% of their total revenue on average, a milestone for an industry that has been chasing fees for decades.

But RIAs have profit margins of 25%, and the better-managed ones reach 35%, according to Armitage. That’s the tangible value that makes them so attractive to private equity and other buyers.

While acknowledging the strength of the market and valuations for RIA sellers right now, some are quick to note that assets in general have rebounded since hitting bottom in March 2009 during the credit crisis.

Since then, the S&P 500 is up more than six times from its low of 666 during the credit crisis. Why should RIAs, which book fees based on the ups and downs of clients’ assets, be any different?

“Capital is cheap, dealmaking is plentiful and assets are in demand,” said Alois Pirker, research director of wealth management at Aite Group. “But it’s a fragmented market and firms have a hard time getting to the right scale.”

“You could say it was crazy how inexpensive things were 10 years ago,” said Robert “RJ” Moore, CEO of Private Advisor Group, an RIA and LPL Financial’s largest branch with $29.6 billion in client assets.

“Private equity firms are sitting on something like $1 trillion to $2 trillion in cash,” Moore noted. “That’s a massive underpinning to the M&A market. That cash has to get invested. Private equity firms don’t get paid for cash sitting in a fund.”

Not all RIAs will have a premium 18 times to 20 times their EBITDA valuation, of course. Thrivent’s Armitage notes that firms typically undergo a variety of valuations, including a valuation done for a potential internal sale or transaction. That could place a multiple of seven to eight times EBITDA on an RIA, or less than half the current talk of the market.

That’s where the deal-making pixie dust comes in. According to Armitage, an RIA seller and buyer can sit down and look at ways to boost the firm’s cash flow in the acquisition’s aftermath, upping a deal’s multiple more favorably for the seller.

For example, what kind of savings would a merger create if the seller’s human resources department or chief financial officer were eliminated, or does the combined firm create scale that puts pressure on vendors to lower prices, she said, all bettering the bottom line.

“How are you calculating EBITDA?” Armitage asked. “The more crafty the financier is, the more magic or sparkle they can add to sizzle the deal.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound