Election could be big loss for those with capital gains

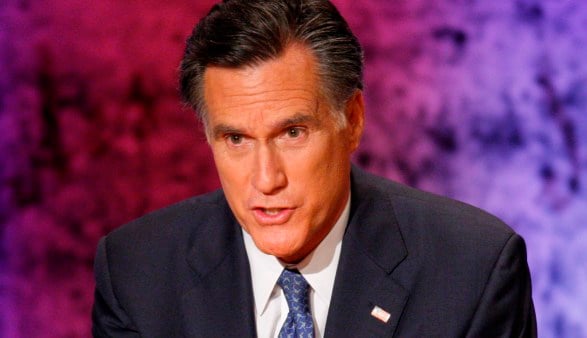

President Barack Obama and Republican opponent Mitt Romney want to move the top capital gains tax rate in opposite directions, with a single number emphasizing their divisions on economic and fiscal policy.

Romney proposes keeping the current 15 percent capital gains rate for the estimated 2 percent of households making more than $200,000 a year and eliminating investment taxes for everyone else. Obama wants the rate to rise to 23.8 percent as scheduled in 2013.

Their differences on capital gains reflect the presidential candidates' broader disputes over the tax code and how much of the tax burden should rest on the nation's highest earners. Obama says he's seeking fairness through higher levies while Romney maintains that tax increases would impede economic growth. Because of that divide, investors deciding when to sell their assets will have billions of dollars riding on the election's outcome.

“It's significant to go from 15 to 20,” said Tim Speiss, a partner in charge of the personal wealth group at EisnerAmper LLP in New York who said in cases where asset prices are at certain levels, his clients are considering selling late in 2012 before the scheduled rate increase. “It makes it much more significant if you're going to take it to 23.8.”

Scheduled Increases

The current 15 percent top capital gains rate compares with a 35 percent top tax rate for ordinary income. Unless Congress acts, the top capital gains rate will increase to 20 percent in 2013, raising $36 billion over 10 years, according to the administration. An additional 3.8 percentage point increase for the highest-earning taxpayers is set to take effect in 2013, to help pay for the 2010 health-care law.

Romney and Obama would narrow the current 20 percentage- point gap between the top ordinary income and capital gains rates. Obama's most recent budget called for a 39.6 percent top tax rate and a 23.8 percent capital gains rate, for a 15.8 percentage point difference. Romney wants to cut the top ordinary tax rate to 28 percent, yielding a 13-point gap with the 15 percent capital gains rate.

Congress set capital gains and regular income tax rates at 28 percent in the bipartisan 1986 tax code overhaul signed by President Ronald Reagan. Subsequent cuts in the capital gains rates and increases in ordinary income rates led to today's margin between the two.

Taxing the Top Earners

The preferential rate on long-term capital gains provides benefits that accrue mostly to taxpayers at the top of the income scale, making the issue a crucible for political differences over how to tax the highest U.S. earners. The debate over one of the most significant tax breaks enjoyed by the top 0.1 percent of earners centers on whether lower capital gains rates are a boon to investment or an unfair advantage for the wealthy.

Eliminating preferential rates on capital gains and dividends would reduce by 5.8 percent the after-tax income of households making more than $1 million a year, compared with a drop of 0.9 percent for all U.S. households, according to the Tax Policy Center, a nonpartisan research group in Washington. Romney had $12.1 million in long-term capital gains in 2010, or more than half his income, according to his tax return. Some of that money came from the carried interest, or profit share, stemming from Bain Capital LLC, the private-equity firm he led.

When to Sell Assets

“If you want to tax the rich, a really effective way to do it is to tax capital gains,” said Leonard Burman, a professor at Syracuse University who said the lower rate drives taxpayers to search for ways to make regular income look like capital gains.

Because taxpayers can choose when to sell assets and realize capital gains, this kind of income is more sensitive to tax rate changes than wages.

“The magnitude of the response of capital gains realizations to changes in tax rates has been a topic of considerable debate,” the nonpartisan congressional Joint Committee on Taxation wrote in 2011.

Obama describes his proposal to raise capital gains taxes for high earners as a matter of fairness. In addition to the higher base rates, Obama wants to impose a so-called Buffett rule that would require the highest earners to pay a minimum tax of 30 percent, effectively raising the top capital gains rate higher.

‘Richer You Are'

“Capital gains are taxed at 15 percent,” Obama said in August 2011 at a town hall meeting in Illinois. “Now, your income taxes, you're not being taxed at 15 percent, most of you. And as a consequence, these days the richer you are, the lower your tax rate.”

Romney and his backers say higher tax rates risk damaging the economy.

“The president wants to raise the capital gains tax rate,” Romney said in a Jan. 24 interview on the Fox News Channel. “If he does so he will kill job creation in this country to some degree, depending on how much he raises it.”

In 2010, the most recent year for which preliminary data are available, U.S. taxpayers reported $320 billion in capital gains, most of which are taxed at preferential rates, according to the Internal Revenue Service. The congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that lower rates for capital gains and dividends are costing the Treasury $93.1 billion this year in forgone revenue.

For and Against

Underlying the Obama-Romney debate are arguments for and against having a preferential tax rate for capital gains.

Advocates of a lower rate contend that capital gains taxes reduce the after-tax rate of return on new investment, discourage people from putting their capital at risk and impose taxes on savings.

“It will decrease investment,” said Peter Schiff, chief executive officer of Euro Pacific Capital Inc. “It will raise the hurdle rate.”

Capital gains rates have fluctuated over time, and there's no clear correlation between lower taxes and economic growth or investment, said Laura Tyson, an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley who was an adviser to President Bill Clinton.

“The evidence actually that a lower rate on capital gains actually changed the amount of investment that occurred over time was actually pretty weak,” said Tyson, who advocates raising capital gains rates to help pay for reductions in the corporate rate. “The evidence is divided. The effect isn't large.”

1987 Through 1989

For example, in 1987, 1988 and 1989, the three years after the capital gains rate was raised to 28 percent while the individual tax rate was lowered to 28 percent, the U.S. economy grew by 3.2 percent, 4.1 percent and 3.6 percent. That was slower growth than in the three previous years and faster growth than in most of the period since 2003, when the most recent capital-gains rate cut happened.

Looking at past economic performance after rate changes obscures important developments in the global economy, said Jim McCrery, the former top Republican on the House Ways and Means Committee. Capital is more mobile now, he said, and higher taxes in the U.S. will drive investment out of the country.

“There are a lot of places around the world that are more attractive for capital today than there were back in the '90s and certainly the '80s and '70s,” said McCrery, who is lobbying for a coalition of companies that wants to keep the current tax rate for capital gains and dividends. “Our tax system didn't matter that much. Today is different.”

Double Taxation

Besides the debate about investment and fairness, the back- and-forth arguments on the importance of preferential rates revolve around whether they mitigate the double taxation of income that already has been subject to the 35 percent corporate tax.

“You have to look at both levels of taxation to understand why we have a 15 percent capital gains tax rate,” Romney said in the Fox interview.

There are many cases in which the double-taxation argument is untrue or only partially true, Burman said. Taxpayers can earn capital gains from assets such as real estate that aren't subject to corporate taxation, and many companies don't pay the full 35 percent tax. Investors receive the benefits of tax deferral, because capital gains taxes aren't due until assets are sold.

Furthermore, assets that aren't sold when someone dies can pass to heirs with the cost basis set at the value of the time of death. When heirs sell the assets, they owe capital gains taxes only on the difference between the sale price and the value at death.

Separating out different kinds of capital gains is tough if not impossible, said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former director of the Congressional Budget Office who was an adviser to 2008 Republican presidential candidate John McCain.

“Have one rate, and then just fight about how high it should be,” Holtz-Eakin said. “Which we do.”

--Bloomberg News--