Is greed really the totality of the explanation for what drives bad behavior by financial advisers and stockbrokers?

When the financial advice industry, populated by roughly 320,000 financial advisers and stockbrokers, discusses the phenomenon of advisers acting badly and harming clients through theft or a lack of ethics, industry executives and financial advisers take a deep breath, hit the mental repeat button and then typically trot out the Bad Apple explanation.

This is how it goes: They blame the so-called rogue broker who stole money from that little old lady in Topeka, Kansas, a sainted grandmother who volunteers each week at church. The financial adviser or broker salesperson acted solo; it was his greed alone that was to blame.

The broker-dealer or registered investment adviser he worked for — and the vast majority of bad actors in the financial advice industry are men because the overwhelming majority of financial advisers are men — had nothing to do with the adviser’s misdeeds.

And that’s the end of the story.

Remove the bad apple from the bunch, and advisers and clients at that firm will continue to flourish, particularly if they work under the belief that the stock market may return to record highs seen just last year. The financial advice industry without the bad apples, as many senior executives and advisers like to pitch it, is almost as innocent and pure in heart as the Garden of Eden before a certain fruit was digested.

But that perception of the financial advice industry, where registered investment advisers earn more profits as they gather more assets and brokers generate higher commissions from selling more products, fails to jibe with the many motivating factors that can trigger a financial adviser’s greed or the need to generate more sales dollars or higher asset levels.

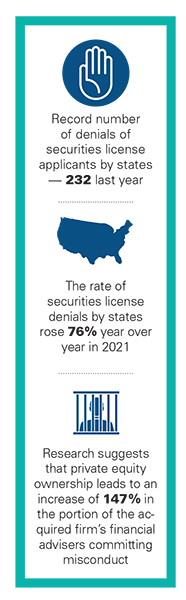

“During the pandemic, brokerage firms were trying to bring in anybody who could bring in business,” said Joseph Rotunda, director of enforcement at the Texas State Securities Board. He cited the record number of denials of securities license applicants by states — 232 last year — as an indication that the financial advice industry was willing to look the other way when hiring salespeople who were simply unfit for the job.

“There was a new demographic of retail investors out there pumping money into the market,” Rotunda said. “It was a boom time until almost a year ago, and broker-dealers needed to hire.”

The rate of securities license denials by states increased 76% year over year in 2021, he said, adding that the individuals rebuked weren’t simply white-collar criminals who had previously been barred or suspended from the securities industry.

“It could have been a person with some kind of financial background who simply couldn’t pass the required test but then went on to sell private securities anyway,” he said.

That’s not to say the financial advice industry is teeming with advisers who lack ethics. Quite the contrary. But it’s worth noting the motivations of individuals that may lead to questionable business practices.

According to information provided to InvestmentNews in 2015 by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority Inc., about 12% of registered securities professionals have some type of disclosure event on their BrokerCheck records.

The events range from customer complaints and regulatory actions to a broker’s financial problems, such as bankruptcies and Internal Revenue Service liens. But disclosure events are often seen as red flags by both investors and the industry.

Two recent disparate but far-reaching events, the rush by private equity investors to buy registered investment advisers and the charge by individual investors to buy securities and investments online during the Covid-19 pandemic, provide a window to view what motivates financial advisers and institutions that may work in consort and cause clients harm.

A study by professors at the University of Oregon published at the end of last year drew a red line under private equity funds buying RIAs at a frantic, breakneck pace.

“Does ownership by private equity firms encourage or deter financial misconduct?” asked the study, titled “Private Equity and Financial Adviser Misconduct.” “We examine this issue by analyzing the records of individual financial advisers around buyouts of investment advisory firms by private equity. Our estimates suggest that private equity ownership leads to an increase of 147% in the percentage of the acquired firm’s financial advisers committing misconduct.”

The unseen but pronounced force of pressure to sell products is one potential explanation for the rise in adviser misconduct after such private equity deals, according to the report.

“Financial advice is an opaque, complicated product for many that is purchased infrequently, and thus perhaps there is scope to take advantage of customers,” the study states. “The increase to firm profits by charging extra fees or placing clients in inappropriately expensive financial products may outweigh the costs of occasional violations and their associated penalties. Employees may also feel increased pressure to perform under [private equity] ownership.”

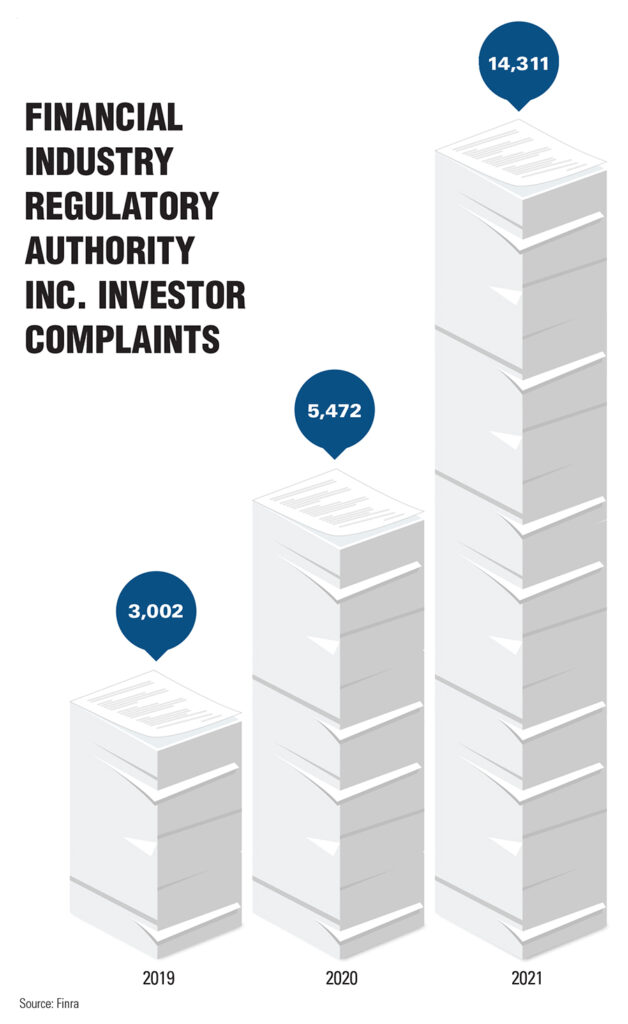

Meanwhile, investor complaints about brokers and broker-dealers have skyrocketed in recent years, corresponding with the rise of the pandemic, according to statistics published by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority Inc. Investor complaints, which totaled just 3,002 in 2019, nearly doubled the next year to 5,472 and reached an astounding 14,311 in 2021.

A Finra spokesperson said that the sharp rise was due “primarily” to the meme stock events of January 2021; that’s when Robinhood, the commission-free trading application, restricted trading in certain meme stocks, which had become the darlings of small investors during the pandemic.

Shut out from trading, investors panicked and apparently have complained in what appears to be record numbers to regulators.

The Finra spokesperson declined to specify what other reasons have driven the recent increase of investors making complaints against brokers and broker-dealers.

Other industry sources cited digital and crypto investments and online solicitations to clients, particularly older investors, through social media platforms as contributors to the surge in investor complaints during the pandemic and its aftermath.

And don’t forget complaints by investors involving the sale of high-risk private placements like GPB Capital Holdings, those sources said, which have led to the recent bankruptcy of one midsize broker-dealer, Kalos Capital Inc. The firm has been crushed due to legal fees and settlements stemming from GPB sales.

In the context of RIA deal-making and an online trading frenzy, naming greed as the overarching driver for brokers’ bad behavior is simplistic, according to industry executives, attorneys and observers.

“The pressure on advisers probably contributes to it,” said Terry Lister, a consultant and principal at THF Consulting and longtime senior attorney, compliance executive and regulator in the securities industry.

“The private equity guys are not interested in a name or reputation, they just want the return on the investment in the RIA over a period of time,” he said. “Those PE guys, they would dump an adviser in the grease if they thought it would help them meet their goals somehow.”

“I’m sure the advisers have to meet certain targets the firms set. And that means you gotta push guys more and push them into products that are higher commissions or have higher fees,” Lister said. “And that’s what gets some of them into trouble.”

While RIAs have been rolling in the fresh capital private equity managers have invested in their firm, it undoubtedly ratchets up the pressure at some firms, said one senior brokerage executive, who asked to speak confidentially.

“Private equity invests, makes the deal and comes in, and advisers’ lives can be changed: The advisers had their own firm and worked for themselves, and now for the first time they are required to hit goals,” the executive said. “They now have these new numbers to hit and maybe that’s why the incidents go up. The pressure to make money is the age-old problem.”

Greed cannot be denied as a motivating factor for financial advisers’ at times appalling acts involving clients. It’s certainly an obvious reason to push brokers into ethical lapses, but there are other reasons. Financial hardship, for example, perhaps caused by a gambling addiction: The adviser hurts his client because he needs cash quick.

Or the adviser simply wants access to the high life: owning the yacht or Ferrari, making it rain at strip clubs, or dropping cash on art if they aspire to show some taste and class. And some advisers rip off their clients just for the thrill of it.

And there are sad cases of advisers harming clients as a result of financial desperation. The adviser’s kid or wife may be in the hospital, and he can’t afford it. Or the older financial adviser doesn’t have enough money to retire.

Meanwhile, broker-dealer and RIA oversight of brokers and financial advisers can be suspect, particularly if the adviser in question is a rainmaker, meaning he generates lots and lots of revenue.

“It’s all about greed, but you have to look at the steps that lead to it. One way that retail brokers hurt their clients is pure laziness,” said Susan Antilla, longtime industry journalist and gadfly. “Brokers often sell products they don’t understand at all. Sometimes they’re just not smart enough to understand products like structured notes or nontraded [REITs]. And sometimes they don’t bother to do any research.”

“And there is a long history of securities firms looking the other way when rainmakers do bad things, like women colleagues being sexually harassed,” Antilla said. “And corporate penny-pinching on security can also hurt clients.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound