When James Gorman arrived at Morgan Stanley in 2006 after running Merrill Lynch’s thundering herd of financial advisors, senior management at first thought his plans to kick a dysfunctional wealth management business in the pants and boost profits sounded a bit off-the-wall.

Indeed, his own profitability targets for the sprawling network of thousands of financial advisors were met with disbelief initially, according to Gorman’s recent recounting of a meeting at the time to discuss his financial goals for the firm’s financial advisor and wealth management business.

“The first presentation I did to our board was a pretty brutal analysis of our then retail business, which was the old Dean Witter business with a little bit of Morgan Stanley private wealth,” Gorman, now CEO and chair of Morgan Stanley, said at an industry conference this June.

“I’ll give you one fun fact” from that time, said Gorman, who this spring announced that he’ll step aside next year as CEO of Morgan Stanley after a run so far of 13 years that has seen the investment bank and trading firm pivot to wealth management in a big way under his watch. “We paid out that year, in Southern Florida, 17% of our revenues in legal expenses.”

That set off alarm bells. Legal costs should have been 1% of revenues, he noted. How does the firm boost profitability if it’s digging a hole because clients are suing their financial advisors in the wake of the dot.com and telecom crashes of the 2000s and eating up revenue?

“But the other fun fact was our net new money for 2005 for the full year was negative $3 billion for the whole year,” Gorman said. (Morgan Stanley now aims to add $300 billion each year in net new client assets.)

Seventeen years ago, Gorman had the temerity to tell the Morgan Stanley board that he had much loftier goals. “I had an aspiration chart, by the way, and the aspiration on pretax margin was to get to 20%, which everybody thought was completely nuts.”

After years of effort, which included slashing the bonuses paid to recruit financial advisors from competitors, Morgan Stanley now each quarter routinely reports pretax profit margins in the high twenties.

Wall Street executives and financial advisors might think a lot of things about James Gorman, including that he can at times be a bit standoffish personally, but no one would say he wildly miscalculated the potential earnings of a well-run, disciplined wealth management franchise that today is widely recognized as a leader in technology for its roughly 16,000 financial advisors.

Accordingly, Gorman, now 65, a native of Australia and a former McKinsey & Co. consultant, is honored as InvestmentNews’ 2023 Icon.

Through a spokesperson, he declined to be interviewed for this article.

A handful of numbers help depict the changes Gorman has wrought at Morgan Stanley over the past 13 years.

For example, at that industry conference in June, one analyst noted that in 2010, when Gorman was co-president of Morgan Stanley, before taking the reins as CEO from John Mack, the percentage of the bank’s pretax profit from its wealth and investment management group was about 26%. Now it’s up to 52%.

Then there’s the performance of Morgan Stanley stock. The share price has tripled under Gorman’s rule, from $29.40 at the end of 2009 to $85.40 at the end of this June, according to data from Wolfe Research.

Over the same period of time, the share price of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. has just about doubled. In aggregate, the return on the shares of the four large U.S. commercial banks — JPMorgan, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citigroup, collectively known as the money center banks — has also doubled over that time, according to Wolfe Research.

Morgan Stanley’s outperformance occurred during a time when the Federal Reserve has had giant bank holding companies on a short leash; during Covid-19, for example, the Fed put restrictions on banks’ dividends and share buybacks.

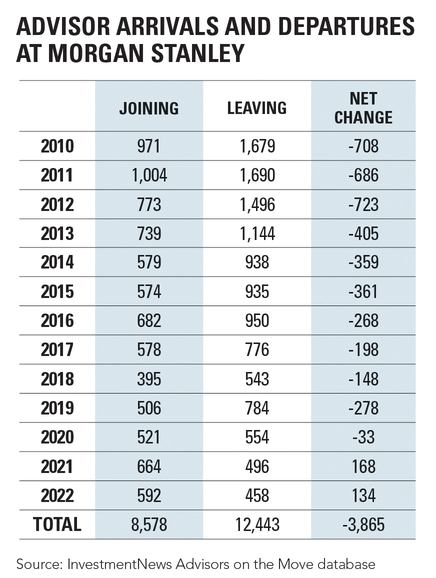

In a way, Morgan Stanley financial advisors have spoken out against Gorman’s policies, including a compensation plan that deferred from 6% to 11% of a financial advisor’s compensation up to eight years. Many bridled at the changes Gorman made to the wealth management business; from 2010 to the end of last year, the bank saw a net loss of 3,865 financial advisors who left Morgan Stanley for another firm.

The net losses on an annual basis were worst right when Gorman became CEO in 2010 and in the years following; the firm has turned that around recently and has seen net gains of financial advisors in the past two years.

“I’ve been critical of policies Mr. Gorman has put into place over the years, but I admire him for sticking to his vision of what Morgan Stanley could be, and it’s reflected in the numbers,” said Danny Sarch, an industry recruiter. “But he put up a fence, and if a financial advisor wants to leave the firm, he or she has to be prepared to climb that fence. And it’s a challenge.”

Gorman’s decision in 2017 to exit an industry agreement known as the broker protocol has rankled financial advisors. The agreement made it easier for financial advisors to move from one firm to another.

His defining moment as head of Morgan Stanley was to buy the Smith Barney brokerage from Citigroup Inc. in two tranches: the first 51% in 2009 and the remainder a few years later. The total cost was $13.5 billion, according to the company.

The success of that transaction and the focus on wealth management led to acquisitions more than a decade later that only bolstered Morgan Stanley’s position as a wealth manager to the mass affluent and wealthy: the 2019 purchase of Solium Capital Inc., a stock plan business that focused on technology startups, for $900 million; the $13 billion acquisition of discount broker ETrade a year later; and the 2021 deal for Eaton Vance, a leading active manager of mutual funds, including the Calvert and Parametric brands.

“When we bought Smith Barney, most of Morgan Stanley was telling me we should be selling retail, not doubling up on it,” Gorman said in June. “When we bought Eaton Vance, everybody said you overpaid by $1 billion. I said, ‘I know, but we bought it.’”

“When we bought ETrade, a lot of people said, well, trading has just gone to zero,” he said at the industry conference in June. “Payment for order flow is in flux. And I said, ‘That’s all irrelevant. What we’re planning is a 10-year transition of the business model, and for that you’ve got to make 10-year bets.’ I would bet there’s very few people in this room who could tell us what we paid for Smith Barney.”

“James is held in high regard at Merrill Lynch and McKinsey,” said a senior industry executive at a rival brokerage firm. “He’s an icon because he truly appears to have the ability to make moves that are two or three in front of the competition. The Smith Barney deal was a master stroke for Morgan Stanley, and it took several years of consolidation.”

“He has a long-term vision and follows through on it,” the executive said. “Gorman elevated wealth management as the firm de-emphasized investment banking. The wealth management business has a higher, more predictable multiple.”

“Gorman appreciated the fact that wealth management is a business that compounds over time, is light on capital and can have relatively high margins,” said Steven Chubak, managing director at Wolfe Research. “And adding best-in-class technology, along with scale from the acquisitions, was a difference-maker.”

“Even as some of the other wirehouses have relinquished market share to independent registered investment advisors or broker-dealers, Morgan Stanley has built a platform where nobody is better than James Gorman on M&A,” Chubak said. “Start with Smith Barney in 2009, then he acquires a top corporate stock plan firm In Solium more than a decade later, followed by ETrade and Eaton Vance.”

“He’s managed to deliver best-in-class growth with regulatory shackles in place after the credit crisis,” Chubak added. “People know he’s a great CEO, but he’s underappreciated.”

According to a 2014 profile in The New York Times, Gorman was raised in a family of 10 siblings in Melbourne, Australia. He studied law and practiced briefly in Australia before coming to New York to attend Columbia Business School.

He joined McKinsey, which is known for churning out brainy number crunchers, but not necessarily charismatic or bold corporate leaders, according to the Times. In 1999, after more than a decade in consulting, he went to Merrill Lynch, a McKinsey client, as chief marketing officer.

Tall and well-tailored, Gorman still bristled in 2014 at being described as a consultant. When asked about the perception that he was a bit distant or cold in personality, he told the Times, “I think anybody who says they don’t care about being liked is lying. I care if my dog wags its tail when I come home. But you’re not going to make everybody happy.”

Gorman can still take issue with how he or Morgan Stanley is being perceived. Despite the firm’s success in wealth and asset management, he wants the marketplace to remember that Morgan Stanley was, is and always will be a leading institution on Wall Street.

“The mistaken perception about our strategy was we’ve become a wealth and asset management business,” he said at the conference in June. “It’s totally false. What we did was attach a viable wealth and asset management business to a world-class institutional business. And we’ve still got the world-class institutional business.”

Relationships are key to our business but advisors are often slow to engage in specific activities designed to foster them.

Whichever path you go down, act now while you're still in control.

Pro-bitcoin professionals, however, say the cryptocurrency has ushered in change.

“LPL has evolved significantly over the last decade and still wants to scale up,” says one industry executive.

Survey findings from the Nationwide Retirement Institute offers pearls of planning wisdom from 60- to 65-year-olds, as well as insights into concerns.

Streamline your outreach with Aidentified's AI-driven solutions

This season’s market volatility: Positioning for rate relief, income growth and the AI rebound